Written by Rowan T.

Introduction

Modern cinematography has heavily relied on the world-building approach since the late 1950s (Taylor, 2017). Early pioneers of the science fiction genre including the 1956 Forbidden Planet and the 1951 The Day the Earth Stood Still depicted alien environments and unbelievable technologies to really cut adrift from the Golden Age of Hollywood movies. At the same time, a change of the background has not changed the narrative and the dramatic structure of the scripts. The protagonist still faced different conflicts with nature, other men or creatures, the society in general, or their own limitations. Most globally recognised films including the original Star Wars trilogy were pursuing the Hero’s journey formula to a certain degree (Sunstein, 2016). This could be explained by the archetypal nature of such challenges that make it easier for viewers to relate their personal experiences to those of the protagonist and build emotional attachments to the characters. However, the large number of successful reboots, sequels, and re-runs cannot but raise a question of whether this effect is created by the unique traits of the heroes or the situations they face or the unique situations they encounter. The aim of this essay is to explore how the concept of situationism is applied in film studies.

Theory of Situationism

The theory of situationism assumes that the behaviours of individuals are largely shaped by the situations they encounter rather than their background (Bleakley, 2018). While situationists do not fully discard the notion of character traits and individual feelings and past experiences, they believe that the specific challenges faced by individuals may produce similar responses and force people to behave in the same manner. These assumptions are also expanded to cultures as a whole where climate, political environment, and other external factors could define the worldviews of all persons affected by these conditions. Situationism was largely supported by such experiments as Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment where randomly selected individuals were assigned the roles of prisoners or prison guards (Zimbardo, 1972). Many participants quickly forgot that they were students within an artificial experiment and demonstrated sadistic behaviours, which largely explained how Nazi conditioning techniques worked during World War II. Other studies conducted by Milgram (1963) and Darley and Batson (1973) confirmed some of these concerning assumptions.

While the aforementioned experiments were criticised by some researchers from the ethical standpoint for the involvement of psychological and physical abuse and the overall violent environment, they could raise many interesting questions within the scope of film studies (Valenti, 2018). On the one hand, movie plots are not limited by these considerations and may depict any scenarios ranging from Nazi camp settings to survival horror environments such as the Saw series. Considering the fact that most critics agreed that situationism could be fully applicable to ‘life-and-death’ contexts, this leads to the debate regarding the relevance of personal traits and experiences of characters within such scripts (Bacon, 2015). These suggestions may be supported by the multiple analyses of the ‘trash horror’ genre characterised by highly stereotypical characters and unique antagonists. On the other hand, the context has been widely utilised as a supporting element of plot development in many films utilising post-modern plot organisation or sci-fi worlds relying on non-conventional settings.

Situationism in Films

The classical 2003 neo-noir Phone Booth thriller may be seen as a good example of the situationist approach in plot development (IMDB, 2020). The main character is punished by the mysterious person forcing them to make difficult life choices and undergo several life-and-death situations. On the one hand, the protagonist background is relevant for the plot since it provides the foundation for the conflict including their past sins, relationships, and personal character traits. On the other hand, the last scene shows the antagonist selecting another random victim, which implies that these experiments took part many times. The popular Saw series of films demonstrates a similar setting where the mysterious Jigsaw Killer tortures others for their ‘sins’ forcing them to undergo a series of deathly traps and personal trials (MacDonald, 2013). While many characters demonstrate their individual traits even in these fierce conditions, the franchise has multiple parallels to Zimbardo’s situationist experiments where past victims change their worldviews and become compliances of the main villain as a response to traumatising situations.

This plot is largely parallel to another cult franchise, the Cube series (Reyes, 2016). It has clear parallels to both Kafkian motives and situationist experiments. As prisoners survive in a strange and highly dangerous setting and see the deaths of their peers, they become increasingly more anxious and aggressive, which implies that situational context may break persons’ will and worldviews to a substantial degree. Overall, situationism may be characteristic of horror and survival horror movies as well as psychological thrillers that depict characters in a state of conflict with the environment or antagonists that involves life-threatening conditions and forces them to make difficult life choices. Another situationist trope is ‘Just Following Orders’ where subordinate personnel members decide to comply with the orders of their superiors that involve homicide, mass murders or other grave crimes (TVTropes, 2020). This element was used in such movies as the 2012 Dark Knight Rises, the 2011 X-Men: First Class, and the 2004 Cube Zero. While the situational settings in these films ranged from dystopian countries with all-powerful governments to difficult dilemmas created by omnipotent antagonists, this situationist trope was used to question the moral integrity of the characters and their readiness to engage in morally questionable activities or suffer various penalties for disobedience.

Existing Debates in the Field

One of the interesting tropes exploring the situationist logic is the ‘accidental travel’ or the ‘fish-out-of-water’ plot exploited by such films as the 2005 Chronicles of Narnia or the 2012 John Carter (Sherman, 2016). These movies expose characters to radically different environments and situations that radically differ from their own worlds or time periods. Under this pressure, many individuals choose to accept a new context and change their behaviours accordingly. These situationist shifts may emerge due to both perceived threats or perceived benefits such as a greater sense of self-fulfilment or purpose in life. Within the scope of the ‘Just Following Orders’ trope, the decision to follow situationism may also be substantiated by the lack of the ‘lesser evil’ option, which is highly interesting within the scope of the ‘authority figures’ concept outlined by Zimbardo (1972) and Milgram (1963). In the situation where any choice will cause harm to innocent others, the characters may adhere to some universal codes of conduct and personal moral beliefs or closely follow the recommendations of their superior officers. The second option usually makes these responses reactive rather than internally defined by their unique traits of character.

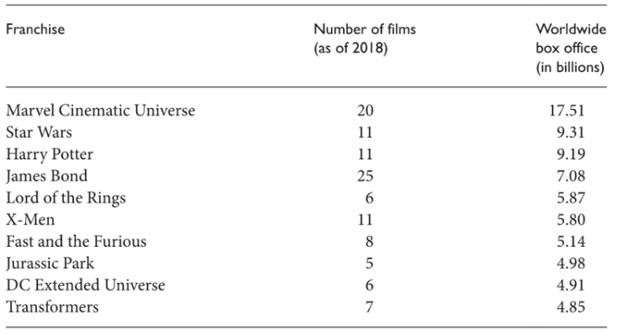

It can also be noted that situationist motives have been applied in multiple war movies and dystopian movies such as the recent Hunger Games, V for Vendetta, Equilibrium, the Matrix, and many others (Ott and Mack, 2020). Overall, it can be summarised that situationist views in this context were largely attributed to minor antagonists who usually succumbed to these pressures due to the lack of strong will and low personal integrity. On the contrary, protagonists and key supporting characters are usually depicted as the persons resisting to all forms of conditioning. At the same time, the personal history of these figures may still demonstrate the elements of situationism such as the past encounters and conflicts shaping their common attitudes towards their main enemy (Bahlmann, 2016). This shifts the paradigm towards interactionism that is presently recognised as a meta-approach combining trait theory with the situationist worldviews. In the most popular franchises of the 2010s presented in the following figure, behaviours of characters are mostly dictated by a person-situation debate with external and internal factors having a proportional impact on the outcomes of personal conflict.

Figure 1: Top 10 Highest-Grossing Movie Franchises (Billion USD)

Source: Ott and Mack (2020, p.45)

Conclusion

The findings suggest that situationism has been widely applied in modern movies as an element of plot setting or a source or major plot conflicts (Valenti, 2018). The most popular genres utilising it were dystopian films, horror films, science fiction films, and thrillers. In all of these contexts, scriptwriters could create conflicts involving harsh conditions similar to the experiments of Zimbardo (1972) and Milgram (1963). However, many of the protagonists involved in fully situationist plots are highly generic, randomly selected, and lack uniqueness and prominent character traits in the first place (Reyes, 2016). Hence, this theory may inherently imply the ‘substitutability’ of individual characters in the manner similar to anonymous participants of the aforementioned psychological experiments. This element may work well with dystopian settings where the emphasis is placed on world-building rather the role of individual protagonists. On the contrary, the movies utilising situationism to a smaller degree use it to differentiate ‘collaborationist’ characters from the ‘hero companions’ demonstrating strength and integrity and resisting the impact of life-threatening situations (Bahlmann, 2016). War movies with the ‘Just Following Orders’ trope may be recognised as yet another example of this conflict exploring the ethical component of situationism in real-life situations.

References

Bacon, H. (2015) The Fascination of Film Violence, Berlin: Springer.

Bahlmann, A. (2016) The Mythology of the Superhero, New York: McFarland.

Bleakley, P. (2018) “Situationism and the recuperation of an ideology in the era of Trump, fake news and post-truth politics”, Capital & Class, 42 (3), pp. 419-434.

Darley, J. and Batson, C. (1973) “"From Jerusalem to Jericho": A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27 (1), pp. 93-107.

IMDB (2020) “Phone Booth”, [online] Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0183649/ [Accessed on 18 January 2020].

MacDonald, A. (2013) Murders and Acquisitions: Representations of the Serial Killer in Popular Culture, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Milgram, S. (1963) “Behavioral Study of Obedience”, The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67 (4), pp. 371-395.

Ott, B. and Mack, R. (2020) Critical Media Studies, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Reyes, X. (2016) Horror Film and Affect: Towards a Corporeal Model of Viewership, London: Routledge.

Sherman, F. (2016) Now and Then We Time Travel: Visiting Pasts and Futures in Film and Television, New York: McFarland.

Sunstein, C. (2016) The World According to Star Wars, New York: HarperCollins.

Taylor, A. (2017) Patricia A. McKillip and the Art of Fantasy World-Building, New York: McFarland.

TVTropes (2020) “Just Following Orders”, [online] Available at: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/JustFollowingOrders [Accessed on 18 January 2020].

Valenti, M. (2018) More Than a Movie: Ethics in Entertainment, London: Routledge.

Zimbardo, P. (1972) Stanford Prison Experiment, New York: Zimbardo, Inc.