Written by Rowan T.

Chapter One : Introduction

1.1 Background

Many organisations are now adopting a process of lifecycle management in an effort to maximise the longevity and thus profitability from their products. This process refers to the management of a product through all stages from inception, primary sales period and decline, and can be a lengthy process, particularly in industries where the early stages of research and development are long (Stark, 2015). The rationale for adopting this approach is that as Prajapati et al, (2013) note, when a product’s lifecycle is extended, there is competitive edge, and improved management of resources. This is particularly important when the research and development of a project is a lengthy process, and subject to stringent regulations, such as in the pharmaceutical industry. Indeed, as Prajapati & Dureja, (2012) indicate, the rising cost of research and development has meant that for branded pharmaceuticals, they not only need to compete with generic products, but also need to identify and increase the available window for capitalising on their investment and achieving effective returns.

The challenge for the industry is that in terms of the overall lifecycle of pharmaceutical products, commencing at the research stage, the time frame for actually selling the product, and thus earning a profit and return on investment is small in comparison to the overall lifecycle. What this has led to is the recognition of a need for extension of patent life and overall product longevity and thus preservation of profit is an important process within the industry as identified by Dubey & Dubey (2010) and Song & Han (2016). Indeed, recent reports from PR News Wire, (2017) also cite increasing pressure on branded pharmaceutical companies which makes the need for understanding lifecycle management strategies even more important. This is due in part to pressure on pricing and enhanced cost of research which, when combined with the stringent regulations in the industry means that when a patent expires, sales will drop as generic products enter the market, increasing competition. What this further indicates is that effective lifecycle management strategies need to be adopted by branded firms, if they are to achieve the necessary return on investment. It is identification and evaluation of these strategies which is the focus of the current work, along with the intent to develop a framework which explains the construct in the context of the pharmaceutical industry.

1.2 Aim of the Research

The primary aim of the research is to investigate the lifecycle management strategies being adopted by branded pharmaceutical companies. To achieve this aim, the following objectives have been set for the work:

- Identify the pressures on branded pharmaceutical companies in terms of LCM strategies

- Examining the commercial impact of these pressures and their contribution to LCM strategies

- Identify the most common LCM strategies being adopted and their benefits

- Identify the factors which impact on the choice of LCM strategies

- Evaluate where appropriate, the impact in terms of revenue/market share on the adopted strategies

- Make recommendations for best practice and develop a framework of understanding.

From these objectives, a series of specific research questions to be answered were developed:

1.3 Research Questions

The work aims to answer the following questions :

- What are the pressures on pressures on branded pharmaceutical companies which lead to the need for LCM strategies?

- What is the commercial impact of these pressures and thus choice of LCM strategies?

- What are the most common LCM strategies being adopted by branded pharmaceutical companies?

- What is the impact in terms of revenue/market share on the adopted strategies?

- Are there recommendations that can be made for best practice in LCM strategies for branded pharmaceutical companies?

1.4 Problem Statement & Research Gap

The research problem to be investigated is therefore how are branded pharmaceutical companies extending the lifecycle of their products, to combat industry pressures and ensure longevity for their products. Although a number of works have considered the role of LCM in the pharmaceutical industry, there is a lack of cohesive evidence on how the industry as a whole is being impacted. The gap this work aims to close is to bring together existing works in the area and provide a comprehensive review and examination of the factors influencing LCM strategy choice.

1.5 Rationale for the Study

The rationale for undertaking the work is that the pharmaceutical industry, and particularly branded firms are under increasing pressure from the entry to the market of generic products, which are challenging market share (Song & Han, 2016). At the same time, increasing consumer knowledge about pharmacology and the potential for alternatives to be sought, means that the need to extend the lifecycle of existing products is vital, given the high costs of research and development in the industry. Therefore, bringing together information and recommendations for best practice in LCM strategies is both timely and relevant.

1.6 Structure of Study

This initial chapter has provided the background and introduction to the work, and provides a foundation for the rest of the study which will be structured as follows:

Chapter Two will provide an overview of the branded pharmaceutical industry, and an examination of lifecycle management approaches and theories before considering briefly how these are applied in the pharmaceutical industry.

Chapter Three will provide a detailed presentation of the methodological approaches adopted for the work, which is focused on secondary data collation. Consideration will be given to choices of research route, data analysis procedures and inclusion criteria for the works to be evaluated.

Chapter Four will present the results of the data collection, identifying the key strategies used in LCM by the branded pharmaceutical industry and indications of their impact on market share/revenue and lifecycle longevity.

Chapter Five will deliver an overview of the work, including identification of key findings and any related implications for the industry. This will be combined with noting any limitations of the work and future research pathways before summing up the overall outcomes and value of the work.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

In order to provide an effective foundation for the work, and the gathering of data in the study area, this chapter will cover key theories of LCM and their application in the pharmaceutical industry, using existing works (Nikolopoulos et al, (2016); Naneva, (2018), and Guseo et al, (2017). To provide further evidence of the value of LCM in this industry, the chapter will also present an overview of the pharmaceutical industry to demonstrate why the need for LCM strategies has arisen (Kappe, 2014; Daidoji et al, 2013). The first area covered is the structure and value of the pharmaceutical sector.

2.2 The Pharmaceutical Industry

2.2.1 Market Size and Branded Firms

The pharmaceuticals market is globally worth in the region of $934 billion, according to 2017 figures, and has a current growth rate of around 5.8% (EuroMonitor, 2017). The market is heavily impacted on by the prevalence of disease, government policies and consumer perspectives and attitudes. The current growth in the sector is being fuelled by reduced taxation and medication costs in countries such as the USA, growth in South East Asia and India, and the increasing prevalence of disease associated with an aging population and poor lifestyle habits (PR NewsWire, 2019). At the same time, the industry has benefited from improvements in research and development approaches and changes in regulations in both the USA and Europe.

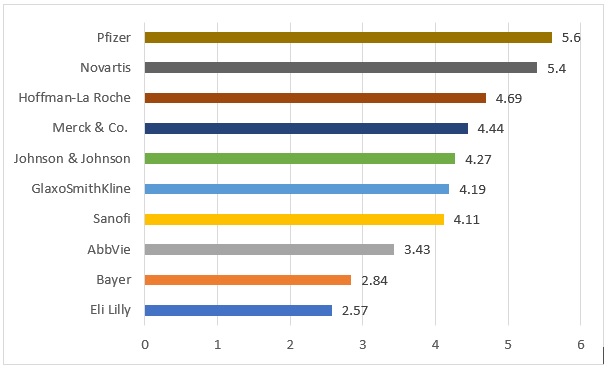

Furthermore, it is also noted that the launch of new products has reduced, and R & D investment is reducing for some companies, despite increased markets as (2018) note. The indicated reasons are high failure rates of new products and the high costs associated with this and the long term investment needed for research, which leads to a low investment return. In other words, and re-affirming the value of this work, pharmaceutical companies are looking at other ways to maintain their profit and the longevity of their existing products but also a need to combat the impact of low priced generic medications which are being purchased in place of branded pharmaceuticals. In terms of market share, the figure below indicates the current market share for the main pharmaceutical companies globally.

Figure 1 Branded Pharmaceuticals Market Share

Source: Pharmaceutical Technology (2019)

From these figures it can be seen that the branded industry dominates around 35% of the overall market, but even the largest of these companies (Pfizer), has less than 6% of the overall market. This underlines the importance of maximising the overall longevity of their branded products, particularly given the lengthy research and development process.

In terms of new entrants the high costs of R & D and the wide ranging regulations impacting on the industry do create barriers to entry, however this can be overcome by the production of generic products. These are copies of existing drugs whose patent has expired and these generic products are increasingly taking a larger share of the market as Efpia (2018) further note.

2.2.2 The Lifecycle of Branded Pharmaceuticals

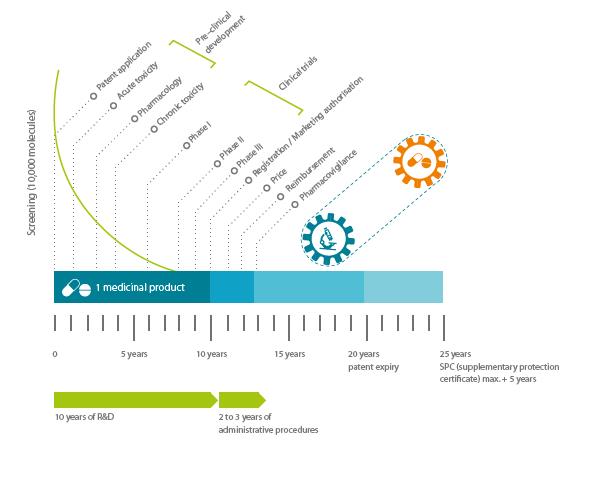

The figure below shows the overall lifecycle of a pharmaceutical products from initial patent application at the pre-clinical development stage, to patent expiry.

Figure 2 Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle

Source: Efpia (2018).

As the figure above indicates, when a product reaches the market, more than a decade will have passed since the first patent application and synthesis of the new substance. This underlines the long and risk process of research and there are indications that the costs of developing a new chemical or bio-entity for use in a pharmaceutical product is in the region of $2.5 million, (DiMasi et al, 2016). This means that the overall investment is large and indeed there is further evidence from DiMasi et al, (2016) that only 1 or 2 in every 10,000 substances synthesised will pass successfully through the lifecycle to become a marketable product. What this identifies is the clear need to maximise profitability during the years when the product is covered by a patent, and thus not subject to copying, in other words the adoption of LCM strategies is vital in the industry. Part of the reason for this is the overall regulatory position in the industry which deserves further consideration.

2.2.3 Regulation and the Pharmaceutical Industry

New pharmacological products brought into the market are generally well protected by one or frequently more patents. These patents mean that firms can have what is known as market exclusivity periods (Grabowski and Kyle, 2007). In other words, no products using the items covered in the patents can be brought onto the market. In the American context, when a drug has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, the patents associated with the products are listed. The most important of these patents is that which protects the molecule or core ingredient of the drug (Branstetter et al, 2016). In general a patents lasts for 20 years following application, but following approval of a patent, the safety of the drug must be tests before market approval is provided if the drugs are to be sold without liability (Bhat, 2005). As noted in the figure above showing the lifecycle, these are long timeframes, and lead to less patent-protected time when the product finally comes to market. Whilst supplementary protection certificates or SPCs can be applied for, extending the protection for 5 years, in Europe at least, this does not always compensate for the loss of monopoly rights as Papadopolou (2016) notes. Again, in the US context, the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act put in place provision for the regulation of branded and generic pharmaceuticals (Gupta et al, 2016). This Act makes provision, once a patent has expired for generic drug manufacturers to file a new application (ANDA) that may include an equivalent bioproduct of a branded drug as noted by Olson & Wendling (2018). The major change made is that generic companies are no longer required to demonstrate the safety of the drug, which was a major barrier to market and is an explanation of why there are increasing generic products on the market. The lower testing costs have facilitated market entry for generic manufacturers but has also reinforced the need for branded firms to identify how they can extend the lifecycle of their existing products and thus retain market share (Naneva, 2018; Nikolopoulos et al, 2016). To do this an understanding of lifecycle management is necessary.

2.3 Lifecycle Management

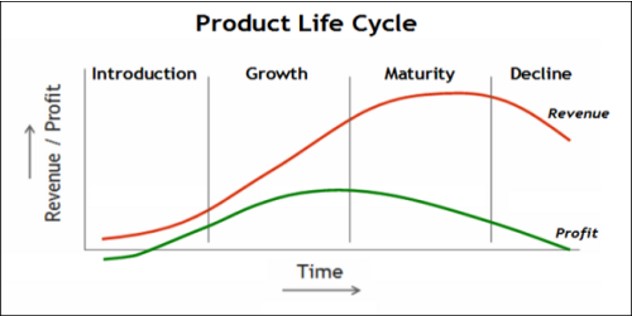

According to Klepper, (1996), product life cycle management is a framework that can identify challenges and opportunities within a defined marketplace for specific products. The intent is that by recognising this framework, an organisation, for example a pharmaceutical company can be better prepared to anticipate changes in the overall positioning, marketing and ultimately longevity of a product. According to the framework, a product will go through distinct stages which are shown in the figure below.

Figure 3 Product Life Cycle Framework

Source: Adapted from Stark (2015)

As the figure indicates, a product goes through five stages, each of which can be impacted on and managed by effective marketing and other strategies. From the perspective of the pharmaceutical industry however, this model misses the overall life cycle which is shown in figure 2 and incorporates pre-market stages of evolution, particularly the research, development and testing phases. Whilst the length of time these take cannot be adjusted to a significant degree due to the need for testing, clinical trials and governmental regulation adherence, they should not be ignored during the development of lifecycle strategies as Prajapati et al, (2013) note. However, once the patent has expired, and thus in the standard product life cycle branded drugs can be seen as being in decline, there are a number of strategies that can be adopted to extend their overall lifecycle and maximise return on investment.

Indeed, several authors have considered the lifecycle and its management in relation to branded pharmaceutical products, including Prajapati et al, (2013); Nikolopoulos et al, (2016) and Wagner & Wakemann (2016), and all identified the importance of recognising the impact of post-patent expiry strategies to extend the longevity of a product and minimise the risks from generic product entry to the market. These authors have highlighted the value of strategies such as reformulation, new combinations and potential from expanded indications to achieve this goal. In other words, lifecycle management is the process of managing, from inception through to cessation of sales of the product, making use of resources and systems and marketing approaches to ensure there is sufficient return on investment for any organisation. In the pharmaceutical context, as already noted, this is vital given the investment that has been made in research and development of products as highlighted by Ellery and Hansen (2012). To understand the approach in more detail and how it can be applied in the branded pharmaceutical industry, a more in-depth examination of each of the stages is undertaken.

2.3.1 Stages of the Lifecycle

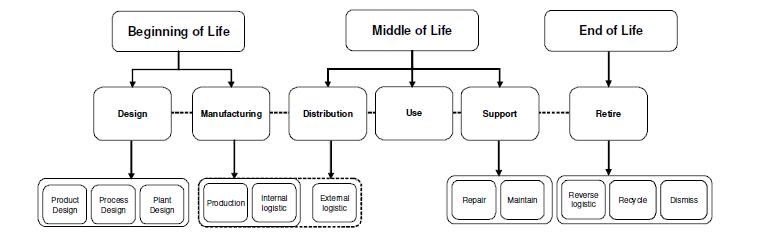

The figure below shows the independent but associated areas of the lifecycle, from a manufacturing and product perspective and suggests there is a beginning of life (BOL), middle of life (MOL) and end of life (EOL) stage, each of which has sub-sections that can be managed by a pharmaceutical organisation.

Figure 4 Lifecycle Stages

Source: Duque Ciceri et al, (2009).

The BOL stage incorporates the design and manufacturing. In pharmacology terms this means identification of a viable molecule, or bio substance that can be used to treat a particular condition. This is then tested and researched and as noted in figure 2 this is a lengthy process, requiring regulatory testing and evaluation before the product can be indicated as cleared for market entry (Jiménez-González et al, 2004). Once these hurdles have been overcome and the product has been cleared for marketing and sales, the cycle moves into the MOL stage. It should however be noted that as in the figure above the final BOL stage of distribution overlaps into MOL as the product is taken to market. During this MOL stage, i.e. when the product is covered by patents and thus cannot be copied, the product will be achieving its maximum profitability and the aim for pharmaceutical companies is that this phase should be extended for as long as possible, with associative deals, affiliations and where possible patent extensions. Again there is a linked phase between the MOL and EOL stage where the need for repair of sales and improvement in the product is necessary. It is at this point that the patent extensions, reformulations or re-branding may be necessary in order to prolong the MOL stage before the product goes into decline. The decline may be due to generic alternatives, other new branded products which supersedes the research done at the BOL stage and meaning that the product is no longer viable. However, there are opportunities to recycle or revitalise medications and it is identification of these which is the core focus of the current work.

2.4 Chapter Summary

The pharmaceutical industry is a complex environment, which is subject to major competition for market share. A primary challenge is how branded firms manage the lifecycles of their products following the expiration of the patents that are designed to protect their drugs and other products. Once these patents, which protect the research, core ingredients and brand names expire, generic drug companies can manufacture cheaper alternatives to branded products, reducing market share. As a result, the length development process needs to be maximised during the middle of life product stage, and steps need to be taken at the move to the end of life stage to find ways of extending the lifetime and thus profitability of the products. Having identified the main factors influencing the need for lifecycle management, the following chapter sets out the processes for gathering data in the area on specific strategies and how they can impact on the longevity of branded pharmaceutical products.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

Taking a qualitative approach, that of drawing together existing works in the area of LCM in the pharmaceutical industry, it was recognised that a very clear, systematic approach to the study design was required (Quinlan, 2019), with the first stage being to identify the most appropriate research philosophy, approaches and data analysis routes. This chapter presents the final decisions made in terms of study design, with rationale for their selection, before considering the important research factors of validity, reliability and ethical conformance.

3.2 Research Purpose & Approach

The initial stage required determining the way in which the work should be conducted, and for this, the research onion framework developed by Saunders & Lewis, (2012) was adopted, as it provides a clear and staged approach to developing an effective methodology, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 5 Research Onion

Source: Saunders et al, (2012)

In other words, the overall design will be logical and the routes adopted appropriate for answering the research questions when this framework is followed. As Denscombe (2014) notes, the first decision requires identifying whether the work is exploratory, explanatory or descriptive in nature. Exploratory works are focused on a desire to explain or explore a phenonmenon or situation, with descriptive works best applied when the aim is to clearly define and identify a situation. The final approach, that of explanatory research seeks to answer “why” a situation occurs (Bell et al, 2018). Re-examining the objectives and research questions, it was clear that an exploratory focus was the best fit for this work as the aim is to understand and explore rather than define LCM strategies in the pharmaceutical industry. In line with this exploratory focus, the work has an inductive underpinning, as the intent is to develop frameworks and theories from evaluation and exploration of a dataset, rather than answer a specific hypothesis which would have led to a deductive underpinning. In line with the inductive perspective, the work also has an alignment with the positivist paradigm due to the aim of providing an examination of reality, i.e. the position in relation to LCM strategies in the branded pharmaceutical industry in line with indications from Robson and McCartan, (2016) on identifying the right research philosophy.

3.3 Data Collection

The dataset for the work came from a systematic analysis approach that incorporated both academic works and commercial reports on the use of Lifecycle Management. The process, which took place in May 2019, involved searching for and identifying works that on LCM strategies in the branded pharmaceutical industry.

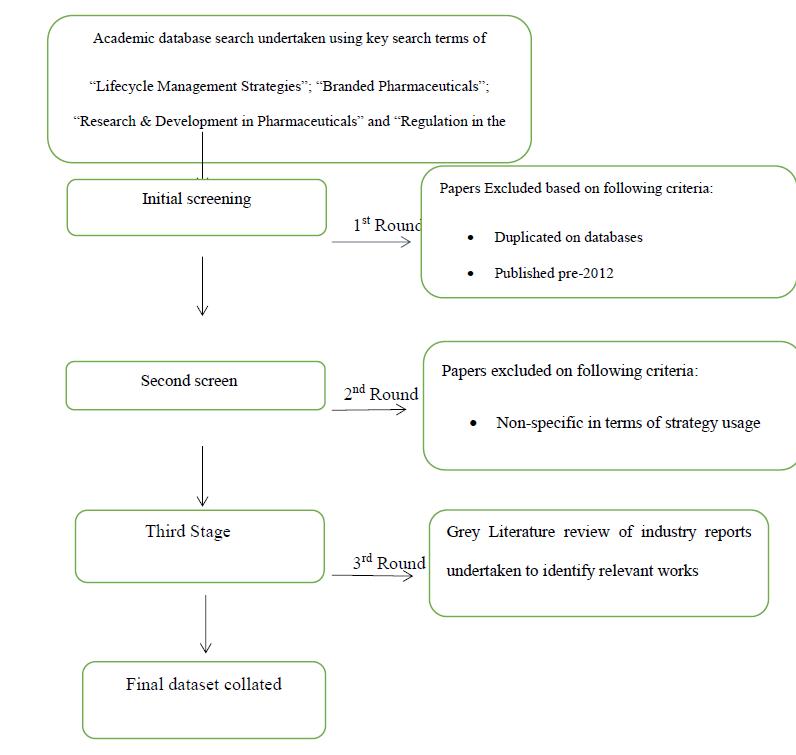

The selected information was chosen based on an initial search using the terms “Lifecycle Management Strategies”; “Branded Pharmaceuticals”; “Research & Development in Pharmaceuticals” and “Regulation in the Pharmaceutical industry”, with the terms being applied across four main databases (ProQuest; Ingenta Connect; JSTOR and Scopus). These sources were chosen as they are multi-disciplinary and would thus ensure that a wide breadth of information could be gathered. In conjunction with the database searches, a grey literature search approach was also adopted to identify recent key reports on LCM strategies in the pharmaceutical industry.

Initial screening of relevant works was reduced to include only those papers published post-2012. The rationale for this is that this covers a seven-year period of change and evolution in LCM strategies in the pharmaceutical industry, and anything prior to this was considered as not sufficiently up to date for inclusion, in line with positivist, real-world focus for the research. The framework below indicates the overall process of selection of items for the dataset:

Figure 6 Selection & Screening Process

Source: Created by author

Once the data had been collated, key themes including specific indication of core LCM strategies were identified to enable a thematic and content analysis to be undertaken. In line with Neuendorf (2016) this approach is a good fit when the aim is to bring together a mix of qualitative information. Given the aims of this work therefore, the thematic/content analysis approach was deemed the most appropriate to adopt.

3.4 Data Analysis

With the data collated the specific analysis process, was undertaken following guidelines from Babbie & Mouton (2001) and required the following steps:

- Identification of top level themes such as “LCM”, “R&D” etc.

- Examination of the frequency of these themes across all the work and the creation of a contextual and thematic table of outcomes.

- Examination of any outlying themes, that were not specific to all the works but which had bearing on the aims of the work.

The subsequent stage of the analysis was to tabulate the outcomes and allow for answers to the research questions to emerge.

3.5 Ethical Issues

A particular value of creating a full data set from existing works is that the need for participant informed consent is negated, as the works are already in the public domain. However, there is still a need to conform to ethical guidelines in relation to reliability and validity of the study and reporting of outcomes. This is especially relevant when selecting works to be included in review such as this so that the overall presentation of the situation is objective and unbiased (Quinlan, 2019). The step by step process, and the framework for selection and inclusion indicated above have ensured that this is the case.

3.6 Validity and Reliability

Saunders and Lewis (2012) in line with their indication of the importance of coherence and transparency in developing study design, note that for a work to be identified as viable, it must be clear that the work is both reliable and valid. In other words, in terms of reliability this means how dependable the data used to draw conclusions is, and importantly how far any findings and conclusions drawn show relevance to other contexts. In essence, the study should have relevance in the problem being investigated. Again, the systematic approach to selection of the data and the coding into themes and patterns through content analysis delivers this reliability requirement. In regards to validity, this construct, as noted by Denscombe (2014) refers to the overall data collection process and importantly, whether the correct factors are being measured or evaluated. In other words, does the data gathered answer the research questions. The focusing of the search criteria and the terms used, which were narrowed down as the search progressed, does provide this level of assurance about the validity and accuracy of the work provided.

3.6 Summary

When undertaking any research work, the design and undertaking of the work is dependent on the robustness of the methodological design and the need to ensure that the right routes, survey instruments and data collection processes are followed. Following the research onion for this work ensured that the right approaches were adopted, and that there is transparency and validity in the selection of works for inclusion, making the study both viable and reliable. Having indicated the processes followed, the following chapter sets out the findings and outcomes of the data analysis.

Chapter Four: Results and Analysis

4.1 Introduction

The indications from the literature review and examination of theories suggests that there may be a number of ways in which branded pharmaceutical companies can extend the life of a product and combat the competition from generic competitors following patent expiration. Examination of a range of papers indicated that there were three main approaches that could be followed, i.e. marketing, research and development and legal routes. Before considering these in more detail, a summary of the core papers and reports used is provided.

4.2 Core Papers and Reports

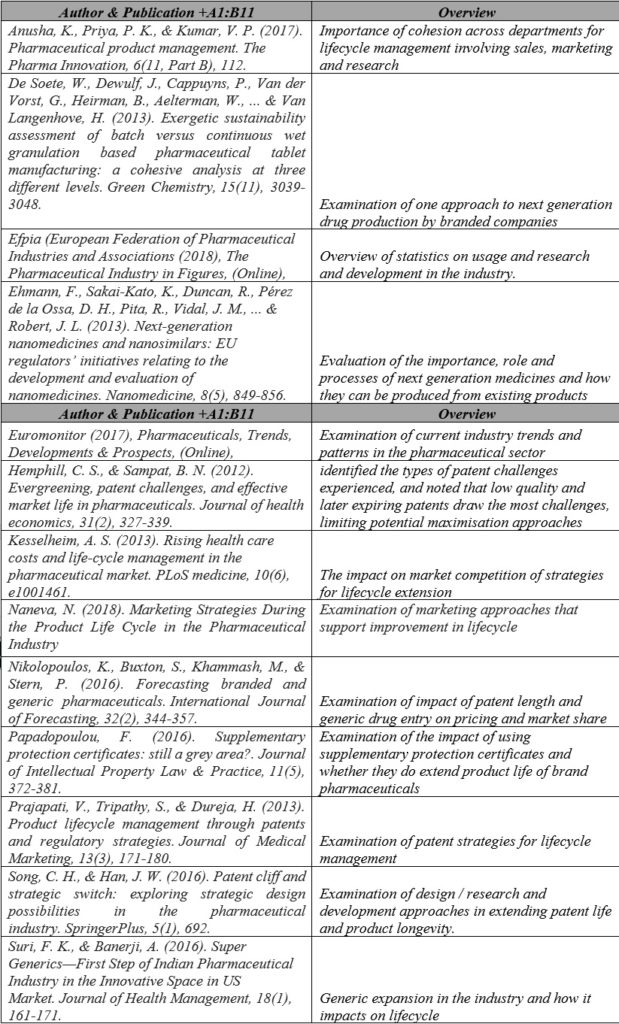

The table below provides details of the core papers and reports used to develop the findings and identify the main routes for lifecycle management.

Table 1 Core Papers & Reports

From these papers, a framework was developed to explain the over-riding approaches of lifecycle management in the branded pharmaceutical industry.

4.3 Models of Lifestyle Management

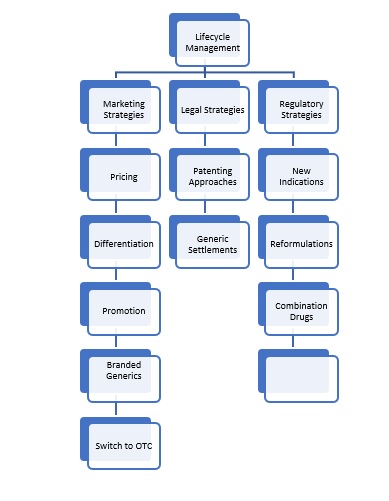

From examination of the papers and reports identified in Table 1 above, the following model was developed to explain the types of strategies applied.

Figure 7 Framework of Lifecycle Management Strategies

Source: Created by author

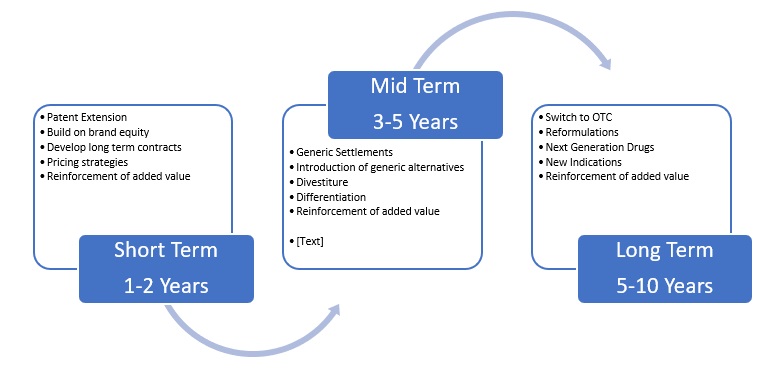

In other words, there are multiple strategies that can be adopted through following one or more of the strategies indicated in the framework, which are covered in more detail in the following sections. What is also clear however is that the three strands need to work together in an integrated way for the strategies to be effective, as it appears that there are short – mid and long term benefits that need to be considered, as the framework below indicates.

Figure 8 Time Frame for LCM Strategies

Source: Created by author

As the figure indicates there is potentially a staged process in the LCM focus for branded companies, which means using a combination approach of the marketing, legal and patent strategies to overcome challenges faced in the industry. From this framework it can be seen that working collaboratively with marketing, research and legal routes can lead to longer lifecycles for branded pharmaceutical products. At each stage however reinforcement of brand value can be used to entrench relationships with customers through the added value approaches indicated below.

4.4 Marketing Strategies for Lifecycle Management

4.4.1 Pricing

When a patent expires for a branded drug, there is an end to the exclusive rights to the market, allowing generic products to use the formulations and offer lower priced products. One approach that can be used to combat this challenge is to decrease the price in direct competition with the generics. However, an alternative, competitive pricing approach can lead firms to focus on segments of the market which are not sensitive to price, and thus there is maintenance or increasing of prices. This is not however an option in regions where medication prices are regulated such as Europe but can occur in countries such as America. In other words, the market is segmented into those areas where either there are long term arrangements with hospitals or fee for service general practice. According to Nikolopoulos et al, (2016), this approach may have the effect of decreasing elasticity of price, which means increasing a branded price drug is an optimal solution. Similarly, when there are line extensions or new formulations this can also lead to improved pricing levels. In essence, this means that marketing strategies need to be considered in a holistic way and not as individual marketing approaches. In other words, pricing strategies need to be co-ordinated with promotional and marketing strategies.

4.4.2 Promotion

Brand equity, which is the reputation and positioning of a product, is built up during the period of protection afforded by the patent protection, when there is a lack of generic competition. Indeed, the increase in direct to consumer advertising, even for prescription medications has enhanced the potential of promotional strategies. In effect, by promoting quality differences between branded and generic products, based on indications of quality control or similar added value such as fewer side effects due to the stability of the formulation as indicated by Naneva (2018). Indeed, work by Naneva (2018) further suggests that effective promotion both before and after patent expiration can reduce the competitive impact from generic products. Moreover,, strong advertising and promotion can lead to entry barriers for generic drugs. The promotional approach may be persuasive relies on differentiating branded from generic products, whilst the informative approach relies on giving information regarding the value that can be delivered in terms of treatment efficacy when compared to generic products (Naneva, 2018; Prajapati et al, 2013). Furthermore, branded products, with their larger resource base are able to provide free samples to hospitals or GPs, which is not something that can be matched by generic companies, who traditionally have a much lower marketing budget than the larger pharmaceutical firms (Naneva, 2018; Song & Han, 2016). Moreover, branded firms have the resources to develop long term relationships and encourage contractual relationships that extend beyond the life of the patent, tying buyers in to deals that ensure the initial introduction of generics can be partially blocked, or at least minimised. In addition to these routes, differentiation, as part of a promotional approach is, at the same time a further marketing approach that can be used to further manage and extend the lifecycle of a product.

4.4.3 Differentiation

The differentiation of branded drugs from generic counterparts following patent expiration is achieved, in line with the promotional approaches indicated above, through indicting that the branded product offers greater value. This may be in relation to new coatings, new formats for delivery (tablet design, patches, liquid for example), and revised packaging although the core product remains the same as noted by Song & Han (2016) and indicated in the Efpia report (2017) as being viable routes to lifecycle extension. This route also underlines the importance of the integrated approach as development of these new value offerings will require research and development. The advantage is that the process will be much faster than the development of the original product, reducing the (BOL) stage, and offering the potential to extend the MOL stage of the lifecycle. Differentiation however is not just confined to the actual product, in marketing terms this can also mean added value services, such as doctor support lines and advice and special discounts for large purchases by hospitals or other health institutions as Kesselheim (2013) notes. Lifecycle management is not however only about extending the lifecycle of a product, it is also important to recognise when a product has gone so far down the decline stage of the product life cycle that it is not economically viable to continue to market it. In this respect, a further marketing strategy is the construct of divestiture.

4.4.4 Divestiture

Kvesic (2008) suggests that divestiture may be a sensible strategy for branded firms facing strong competition from generic newcomers to the market. This may be a viable strategy if other products are through the initial research and development stages and ready to enter the market. In essence, by divesting or ending a product, resources are freed up to support the new product and maintain overall market share for the branded firms, as Hemphill et al, (2012) and indications from Euromonitor (2017) suggest. .There is however another means of dealing with the challenge from generic companies, and that is to either enter into partnerships with new upcoming generic pharmaceutical companies or introduce their own lower cost generic versions of an existing products.

4.4.5 Branded generics

When a generic achieved an ANDA they are given 180 days to exclusively marketing the product. What this means is that the first to enter the market has the potential for large returns. The challenge however is that during the 180 day period, the existing branded products are also allowed to market their own generic medications, without additional need for further authorisation. What this means is that there is a gap which can be filled by subsidiaries producing and subsequently marketing generics, or they provide a license to new generic firms, taking over market share that would otherwise go to new entrants to the market (Kvesic, 2008; Suri & Banerji, 2016). Indeed, this is a common strategy of branded firms, who want to maintain their market share and profitability and combat new entrants to the sector (Anusha et al, 2017). It can potentially be seen that the development of generic products, an approach used successfully in many supermarkets offers a major potential for revenue generation (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Whilst these generic products from branded pharmaceutical companies may impact on the profit achieved from their branded products, the net impact is that as a company, the revenue stream is maintained. This is important in the context of lifecycle management because the focus should not necessarily be on maintaining one product, but ultimately managing the product portfolio to generate profit for the business as Voet (2016) points out. Although not a long term strategy it does prevent some generic firms from entering the market in the short term and as a result can be a viable strategy for extending, for a short period, the market share of branded pharmaceuticals. A further alternative in the marketing strategies approach is to move the products to over the counter, rather than prescription products.

4.4.6 Switch to OTC

In certain situations, regulatory bodies such as the FDA in America will grant branded drugs the right to be sold over the counter for self-medication purposes. Where this potential exists, it increases the routes to market available for branded pharmaceuticals and thus extends the overall lifecycle of the product, (Prajapati et al, 2013). OTC products can manifest in two distinct formats. The first is sales following assessment by patient needs and discussion with the patient. Clearly these are somewhat more regulated and means alternatives may be available to patients to make a selection (Berndt, 2003). The second OTC approach is making the medicines available freely to consumers, without advice. Again, there is a potential for customers to do their own research and make their choices based on areas such as price, value and efficacy of the product, and added value such as after sales advice, lack of side effects or similar (Pujari et al, 2016). The challenge with adopting an OTC strategy is that the additional regulation required to release the product as non-prescription can be a lengthy process During this time, other generic products may take over (Kesselheim, 2013; Naneva, 2018) and it is here that branded firms need to use their existing brand equity to leverage customer preference for the branded over the generic products as indicated by Kohli and Buller (2013).

Marketing strategies such as those indicated in the sections above, are however only one, consumer focused approach for combating threats from generic products, and may only extend the life cycle of existing products for a short term as competition will continue to increase as more generic products enter the market. As such, other back-up and supplementary strategies need to be considered, such as new approaches to research and development in relation to the existing products.

4.5 Research and Development Strategies

The value of adopting a research and development strategy as part of lifecycle management strategies, is that they are a means of building on existing reputations and working with existing, rather than new drugs. In other words they can make use of an extension of the patent and thus a longer period of market exclusivity (Song & Han, 2016). On the patient side, new research and development routes can improve convenience for patients with new delivery systems, remove existing side effects, or allow for existing products to receive approval for treating new conditions. In other words, this strategy is founded on utilising the existing knowledge within a branded pharmaceutical firm and can frequently obtain new patents more speedily than brand new formulations or substances.

4.5.1 New indications

When a new product is released onto the market, even when it has gone through the regulatory and patent process, side effects often manifest after entry to market. As part of a process of lifestyle management, however, new uses or positioning of a product can be a means of extending the profitable life of a product. The value of this process is that there is a dramatic reduction in research costs and times and thus can lead to a longer period of market exclusivity (Kvesic, 2008; Bhat, 2005). Indeed, indications from recent pharmaceutical industry reports (Euromonitor, 2017; Efpia, 2018) are that more than 84% of current branded drugs have gone through a process of secondary approval to provide new indications. What this suggests is that new indications may be a low cost means of extending the overall lifecycle of branded products. Indeed from a promotional perspective, it is noted that new indications may be marketed by leveraging the brand equity of the original product. This is because where a product can be used for multiple products, this means that there are also multiple markets where the products can be sold, increasing overall market share and thus return on investment for the organisation (Anusha et al,2017; Naneva, 2018). It should be noted however that new indications, do not necessarily mean a whole new product, rather that existing properties are applied in different contexts. New variations are however another R & D approach that can be used, known as reformulations. .

4.5.2 Reformulations

A reformulation approach takes the primary active ingredient, molecule or bio substance that is formulated in a different way to provide new doses, manage side effects or improve efficacy. At the same time, a reformulation can also occur when regulations change and there is a need for a change in compliance achievements. What makes this a viable strategy is that reformulations require a much shorter time for approval and can mean a further three years of exclusivity (Bhat, 2005). Achieving a reformulated product can be technically challenging and may involve addressing or challenging existing patents but the expenditure is viable as achievement of a positive outcome can raise barriers to generic products coming onto the market as Hemphill & Sampat (2012) note. Indeed, as Dubey & Dubey (2010) note, more than 60% of new drug approvals in the USA are for reformulations indicating that this is a highly popular strategy by branded firms. What branded firms need to remember however is that any new patent and thus market exclusivity is only given to the reformulation and does not extend this privilege to the original product (Song & Han, 2016). As a result other research approaches may also be necessary, for example combination drugs.

4.5.3 Combination Drugs

This approach is again a widely used lifecycle management strategy. The term refers to two or more active ingredients that have approval which are combined in a single dosage delivery system. The newly designed product is however subject to a new patent, which is only granted if there are clear improvements in patient treatment and management (Bhat, 2005). What is important is that the combination product usually moves far more quickly than for originally developed drug products, reducing the BOL stage dramatically and increasing the MOL stage (Naneva, 2018) There is limited research into the overall value of this strategy, and it would benefit from further research in the future. In a similar vein, taking research and development strategies further, there is also potential in the development of next generation drugs.

4.5.4 Next-Generation drugs

Next generation drugs refers to a product that is developed using innovative technology to improve and ultimately replace an existing product. In the pharmaceutical industry it is vital that when this occurs, there is a significant improvement and thus advantage over competitive products (Naneva, 2018;Suri & Banerji, 2016). In this industry sector the approach is to work altering the chemical structure of the active ingredient. A new patent is required due to the altered nature of the product, but again as with other research and development strategies, the process is much shorter than for a brand new product (Ellery & Hansen, 2012). Whilst this would appear to be a viable and potentially lucrative strategy, there is limited evidence for its value in terms of delivering improved market share, productivity and ultimately extended lifetime of a branded pharmaceutical product (De Soete et al, 2013). Therefore, whilst recognising the potential value of next generation research and development, further empirical evidence is needed to confirm its viability as a significant strategy in lifecycle management.

Certainly, for branded pharmaceutical companies, the maximisation of their existing knowledge and research facilities to undertake new approaches and develop extended products would appear to be a highly viable and cost effective means of lifecycle management. However, the actual value of these products is not currently clearly understood and further examination is needed to empirical assess their true commercial value when compared to other strategies already discussed. The final strand of lifecycle management that appears to exist is the use of legal strategies based on managing the protection afforded to initial products through patents and other regulations that control the overall competitive market.

4.6 Legal Strategies

In the pharmaceutical industry there are clear legal constraints and regulations which firms must adhere to. Not only does this mean a need to ensure safety compliance in testing and development of new products but also provides the control which branded pharmaceutical firms can exercise over the main active ingredient of the drug, and the other components used to create the final product. In other words, patents can be applied for to cover all elements of a product as well as the final product. This affords firms strong protection against generic competition, at least until the patent expires. The challenge is that with any legal framework there are always means for generic firms and other competitors to find a means of working around the patents. Whilst they may be subject to infringement cases, many generic firms will take a risk in attempting to circumvent the method of manufacture, chemical variants, and other processes, all of which can be patented by a branded pharmaceutical designed. With this in mind, in an attempt to improve the longevity of a product can also be increased through legal approaches once a patent expires.

4.6.1 Patenting strategies

A patenting strategy means covering all aspects of a drug and this may mean having more than 10 patents on one product. The patents may be on manufacture, ingredients or processes (Hemphill and Sampat, 2012; Prajapati et al, 2013). Patent applications are on the increases, as are challenges to these patents, but this does not mean that there is no potential for using a cohesive legal approach with patents, covering all elements of the product to enable extended protection. In addition, with a small adjustment a patent can also be extended, (Papadopoulou, 2016), however this only offers a few additional years. The benefit of this is that it provides additional support and time to work on other strategies that can further extend the lifecycle such as the marketing strategies indicated above. There is however one final legal strategy that can be followed, which involves directly engaging with generic competitors.

4.6.1 Generic settlements

If a generic manufacturer appears to be eroding a large section of the branded market, the route exists for branded firms to either offer a licence to use their name, or they may be encouraged to drop a challenge to patents, or even become a subsidiary of the branded firm (Nikolopoulos et al, 2016). The benefit to the branded firm is that they have control, whilst the generic manufacturer gains access to a wider set of resources and capability for their lower priced products. Given that as Efpia (2018) note, in Europe the generic market share is around 40%, this approach would ensure that the branded firms can retain some of the profit available during the post-patent expiry stage. Settlements often appear to occur when a first generic producer enters the market following patent expiry, due to the 180 day exclusivity period that these “first on the market” generics can gain. As with the research and development strategies, legal approaches are not fully explored and their impact not widely understood. However, they remain as additional options for branded firms as part of a wider lifecycle management strategy.

4.7 Chapter Summary

The results of the search into the range of strategies used by branded pharmaceuticals has identified that there are three main approaches that can be taken – marketing, research and development and legal routes for a more efficient management of the lifecycle of branded pharmaceuticals. Whilst specific data on the sales impact of these strategies could not be identified, due to commercial sensitivity and a lack of empirical data from organisations, there are indications that the research and development and legal strategies can be a short term option for firms. However, effective marketing and the range of marketing strategies that can be adopted would appear to be more viable in the long term. What is noted however is that all the evidence suggests that a cohesive approach to lifecycle management is necessary, incorporating a range of strategies that are integrated into an overall focus on retention of patent protection, via extension, but supporting this with additional research and development and focused marketing activities. The final chapter in this work thus discusses the overall findings and reviews the study and its implications for pharmaceutical companies.

Chapter Five: Discussion and Conclusions

5.1 Introduction

The intent in undertaking this work was to bring together information about the ways in which branded pharmaceuticals employ lifecycle management approaches to ensure longevity of their products. The need for the work arose from a recognition of the pressures faced by these organisations as their patents expire and the profit-making time of their products is reduced. From examination and drawing together works from a range of sources, a clearer picture of the overall situation and how LCM strategies are utilised in the industry has been drawn. Before examining the key findings, a number of limitations to the work need to be identified.

5.2 Limitations

The main limitation was a lack of access to empirical data from branded pharmaceutical companies on how effective each of the identified strategies was for extending the lifecycle. Although this has impacted on the definitive evidence for identifying which is the most significant strategy, it is not felt that this has detracted from the value of the work in terms of drawing together a framework for LCM in the branded pharmaceutical industry.

5.3 Summary of Key Findings

From the evidence examined, it is clear that branded pharmaceuticals are under high pressure to find ways of improving and extending the profitability stage of the product life cycle, defined as MOL by Duque Ciceri, (2009). In other words, the lengthy research and development process, which can be up to 10 years when clinical trialling and drug approval regulations are taken into account means that the MOL stage needs to be extended with strategies that encourage continued purchase. It was noted that these strategies can come from a legal standpoint, either licensing to generic manufacturers so that some level of revenue is retained during the post-patent expiry stage, or through development of lower cost generic medications from the branded firms themselves. Evidence from Efpia (2018) suggests that the majority of branded pharmaceuticals firms will follow at least one of these routes to combat the challenge from generic manufacturers. What is less clear is what level of return can be achieved, and this is an area that would need further investigation in future works.

Similarly, legal approaches to enhancing protection through extensions of the patent are also widely recognised and utilised in the industry. As noted by Hemphill and Sampat, (2012) and Prajapati et al, (2013), patents can be applied for to cover ingredients, composition and branding, but also processes. As such, if a new process is developed, that does not require further approval this can be patent protected, creating further barriers to generic entry to the market. Again however, specific data on the level of improvement in the longevity of the lifecycle was not available, and legal strategies can take time to implement. What this means for branded firms is that they may still face strong competition as generics find innovative means to bypass the patents once the core patent for selling the medication has expired as indicated by Suri and Banerji (2016).

Potentially more effective is the adoption of a marketing focus to lifecycle management. Due to the diversity of approaches that were identified as coming under the marketing strand such as pricing strategies, promotional approaches, differentiation and divestiture, it appears that marketing focus for LCM has a wider impact on improving the longevity of branded pharmaceuticals (Naneva, 2018; Anusha et al, 2017). In essence, building on company reputation and customer loyalty, i.e. using the brand equity for leverage appears to deliver the highest potential. Although specific figures were not available for the study, it was noted by Kesselheim (2013) that the lower research time and costs for reformulations is increasing the usage of this approach. Indeed, similar trends were noted by industry reports from Euromonitor (2017) who highlight the value to branded firms of re-investing, reviewing and extending research and development knowledge in industry. When this approach is aligned with a research and development focus, the knowledge within the firm and the introduction of, for example, combination drugs and next-generation drugs (Song and Han, 2016), then the use of a cohesive marketing focus for promoting these products can potentially have a significant impact on the profit-making stage of a product, and thus a greater return on investment.

An objective of the work was to identify how firms choose their LCM strategies, however, the data available, being secondary in nature, did not allow for this to be achieved, and therefore this would need to be examined in subsequent works. However, from the information available, it is likely that the choice of strategy is based on overall market evaluation, level of competition and the positioning of the branded products at the time of patent expiry.

In essence, the main findings are that branded pharmaceuticals need to take an umbrella approach to LCM, and not just focus on one area for ensuring more efficient LCM is part of their future strategy. Importantly as well, whilst the majority of strategies are focused on increasing the lifetime of a branded pharmaceutical, it is also noted that the option of divestiture may be the only route to follow. For example, if a product is patent-expired and generic alternatives are encroaching on market share, it may be better for the company to remove this product and then look at reformulations and associated marketing, rather than attempting to maintain sales. This would be a better usage of resources and recognises that LCM is not just about extending product life but also recognition of how and when to mount challenges (Kesselheim, 2013; Anusha et al, 2017). Taking these findings into account, some recommendations for branded pharmaceuticals on overall LCM approaches can be made.

5.4 Recommendations

Based on the key findings, and using the model developed in section 4.3, the following recommendations can be made to branded pharmaceutical firms.

- When considering lifecycle management strategies, a short-term, mid-term and long term view should be adopted. This is because it appears that legal approaches can deliver only a short term benefit, whilst marketing and research and development can both be applied in the mid- and long term. In other words a future proofing approach to combat generic competition needs to be focused on an integrated approach across all departments.

- Furthermore, it is recommended that in the period leading up to patent expiry (i.e. 18 months to 2 years before) a focused marketing and promotional campaign is developed to reinforce the value of the existing products and where possible tie hospitals and GPs into contracts which run past the patent expiry date. In this way, strong customer relationships can be formed, which will enhance the brand equity and thus reduce desire to switch to generics, irrespective of cost, due to the perceived enhanced value offered by the branded pharmaceuticals (Naneva, 2018; Prajapati et al, 2013; Anusha et al, 2017).

- Alongside this marketing focus, which is vital for effective long term LCM strategies, is the need to consistently review research and development and ensure investment is maintained. It is interesting to note that Efpia (2018) highlighted a trend for a reduction in long term research and increasing focus on reformulations, and next generation amongst branded pharmaceuticals. This points to the recognition of the long lead time from inception to market in the industry and the need to be able to maximise existing knowledge and resources.

These recommendations are made based on the evidence collated and whilst considered viable it is further recognised that there is also a need for further investigation to extend and develop the approaches and viewpoints identified in this work. In this respect, some future research pathways are also indicated.

5.5 Future Research Pathways

Recognising the limitations of this work, it is recommended that empirical industry evidence is gathered for the effectiveness and financial impact of each of the three strands of LCM identified. In particular to confirm the view of this work that there should be a short – mid and long term strategy in place that encompasses all three strands and where each one is effective. As such, either a case study or industry wide survey would be advisable to indicate where the most effective strategies lie. In particular, the impact on market share of patent extensions, generic settlements and licensing agreements would benefit from further exploration. Furthermore, greater understanding of how branded firms choose their LCM strategies would also increase knowledge in the area. In the context of generic challenges, Efpia (2018) note, there is an increasing trend for new generic firms to exploit the research of branded firms following patent expiry, a point also noted by Suri and Banerji (2016). Therefore, more in-depth exploration of the focus of strategies is recommended in any future research.

Similarly, greater evidence is needed for the value of next generation and reformulation research as a lifecycle management strategy. Although the indications from the works considered in this study suggest that this may be an effective way to use existing knowledge and combine this with improving technology and pharmaceutical research, again the empirical evidence base remains limited and therefore more detail is needed on the specific impact of these strategies on the lifecycle of branded pharmaceuticals.

Finally, whilst marketing strategies do appear to offer the greatest potential for return on investment post patent expiry, the specific approaches could not be widely explored within the scope and resources of this work. Therefore, and in alignment with Naneva (2018) and Anusha et al, (2017), it is recommended that work is undertaken which is directly focused on gathering empirical data on the effectiveness of the marketing strategies identified in this work. Combining marketing theory on brand equity and product switching should be a focus of this research as it would identify where and how branded firms can target their marketing during the MOL stage to extend this further and reduce the impact of the EOL stage.

5.6 Summary and Closing Remarks

The pharmaceutical industry has one of the longest timeframes from product inception to bringing to market and is subject to a range of legal and clinical approval procedures. As such, in order to achieve an effective return on investment, it is vital that these firms have a strong lifecycle management strategy to maximise the time when their product is profitable. Given that the branded firms only hold around 30% of the overall market, this need is further increased. Despite the resources available for marketing and developing long term relationships with hospitals, GP practices and other health institutions, branded firms face strong competition from generic manufacturers following patent expiry. This work has identified that there are three core approaches that can be followed, but that these need to work in an integrated way to maximise the potential of a lifecycle extension. Further work is needed to clarify the significance of each approach but as a foundation for bringing together a better understanding of LCM in the pharmaceutical industry it is felt that this exploratory work provided a good foundation for further exploration of what is likely to be an important area of investigation for branded pharmaceutical firms in the future.

References

Anusha, K., Priya, P. K., & Kumar, V. P. (2017). Pharmaceutical product management. The Pharma Innovation, 6(11, Part B), 112

Babbie, E. and Mouton, J., (2001). Qualitative data analysis. The Practice of Social Research, South Africa Edition, pp.489-516.

Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2018). Business research methods. Oxford university press.

Berndt, E. R., Kyle, M., & Ling, D. (2003). The long shadow of patent expiration. Generic entry and Rx-to-OTC switches. In Scanner data and price indexes (pp. 229-274). University of Chicago Press.

Bhat, V.N. (2005), “Patent Term Extension Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Industry,” Pharmaceuticals Policy and Law, 6, 109-122.

Branstetter, L., Chatterjee, C., & Higgins, M. J. (2016). Regulation and welfare: evidence from paragraph IV generic entry in the pharmaceutical industry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 47(4), 857-890.

Daidoji, K., Yasukawa, S., & Kano, S. (2013). Effects of new formulation strategy on life cycle management in the US pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Generic Medicines, 10(3-4), 172-179.

Denscombe, M., (2014) The good research guide: for small-scale social research projects. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. Journal of health economics, 47, 20-33.

De Soete, W., Dewulf, J., Cappuyns, P., Van der Vorst, G., Heirman, B., Aelterman, W., ... & Van Langenhove, H. (2013). Exergetic sustainability assessment of batch versus continuous wet granulation based pharmaceutical tablet manufacturing: a cohesive analysis at three different levels. Green Chemistry, 15(11), 3039-3048.

Dubey, J., & Dubey, R. (2010). Pharmaceutical innovation and generic challenge: recent trends and causal factors. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 4(2), 175-190.

Duque Ciceri, N., Garetti, M., & Terzi, S. (2009). Product lifecycle management approach for sustainability. In Proceedings of the 19th CIRP Design Conference–Competitive Design. Cranfield University Press.

Efpia (European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (2018), The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures, (Online), Available at: https://www.efpia.eu/media/361960/efpia-pharmafigures2018_v07-hq.pdf, (Accessed 2nd May 2019)

Ellery, T., & Hansen, N. (2012). Pharmaceutical lifecycle management: making the most of each and every brand. John Wiley & Sons.

Euromonitor (2017), Pharmaceuticals, Trends, Developments & Prospects, (Online), Available at: https://www.euromonitor.com/pharmaceuticals-trends-developments-and-prospects/report, (Accessed 2nd May 2019).

Grabowski, H. G., & Kyle, M. (2007). Generic competition and market exclusivity periods in pharmaceuticals. Managerial and Decision Economics, 28(4‐5), 491-502.

Gupta, R., Kesselheim, A. S., Downing, N., Greene, J., & Ross, J. S. (2016). Generic drug approvals since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. JAMA internal medicine, 176(9), 1391-1393.

Hemphill, C. S., & Sampat, B. N. (2012). Evergreening, patent challenges, and effective market life in pharmaceuticals. Journal of health economics, 31(2), 327-339.

Jiménez-González, C., Curzons, A. D., Constable, D. J., & Cunningham, V. L. (2004). Cradle-to-gate life cycle inventory and assessment of pharmaceutical compounds. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 9(2), 114-121.

Kappe, E. (2014). Pharmaceutical lifecycle extension strategies. In Innovation and Marketing in the Pharmaceutical Industry (pp. 225-254). Springer, New York, NY.

Kesselheim, A. S. (2013). Rising health care costs and life-cycle management in the pharmaceutical market. PLoS medicine, 10(6), e1001461.

Klepper, S. (1996). Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. The American economic review, 562-583.

Kohli, E., & Buller, A. (2013). Factors influencing consumer purchasing patterns of generic versus brand name over-the-counter drugs. South Med J, 106(2), 155-60.

Kvesic, D. Z. (2008). Product lifecycle management: marketing strategies for the pharmaceutical industry. Journal of medical marketing, 8(4), 293-301.

Naneva, N. (2018). Marketing Strategies During the Product Life Cycle in the Pharmaceutical Industry (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).

Neuendorf, K.A., (2016) The content analysis guidebook. Sage.

Nikolopoulos, K., Buxton, S., Khammash, M., & Stern, P. (2016). Forecasting branded and generic pharmaceuticals. International Journal of Forecasting, 32(2), 344-357.

Papadopoulou, F. (2016). Supplementary protection certificates: still a grey area?. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 11(5), 372-381.

Pujari, N. M., Sachan, A. K., Kumari, P., & Dubey, P. (2016). Study of consumer’s pharmaceutical buying behavior towards prescription and non-prescription drugs. J of Medical and Health Research, 1(3), 10-18.

Olson, L. M., & Wendling, B. W. (2018). Estimating the causal effect of entry on generic drug prices using Hatch–Waxman exclusivity. Review of Industrial Organization, 53(1), 139-172.

Papadopoulou, F. (2016). Supplementary protection certificates: still a grey area?. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 11(5), 372-381.

Pharmaceutical Technology (2019), The Top Ten Pharmaceutical Companies by Market Share (2018), (Online), Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/features/top-pharmaceutical-companies/, (Accessed 2nd May 2019)

Prajapati, V., & Dureja, H. (2012). Product lifecycle management in pharmaceuticals. Journal of Medical Marketing, 12(3), 150-158.

Prajapati, V., Tripathy, S., & Dureja, H. (2013). Product lifecycle management through patents and regulatory strategies. Journal of Medical Marketing, 13(3), 171-180.

PR News Wire, (2017), Pharmaceutical Lifecycle Management Strategies in 2017: Comprehensive Assessment of Strategies Being Implemented by Pharmaceutical Companies Around the World - Research and Markets, (Online), Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/pharmaceutical-lifecycle-management-strategies-in-2017-comprehensive-assessment-of-strategies-being-implemented-by-pharmaceutical-companies-around-the-world---research-and-markets-300452376.html, (Accessed 30th April 2019).

PR Newswire, (2019),Global Pharmaceuticals Market Analysis 2018: Growing Focus on Big Data & Analytics - Precision Medicine and Targeted Drug Development is the Next Focus Area, (Online), Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-pharmaceuticals-market-analysis-2018-growing-focus-on-big-data--analytics---precision-medicine-and-targeted-drug-development-is-the-next-focus-area-300776892.html, (Accessed 2nd May 2019)

Quinlan, C., Babin, B., Carr, J., & Griffin, M. (2019). Business research methods. South Western Cengage.

Robson, C. and McCartan, K., (2016). Real world research. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Rodrigues, V., Gonçalves, R., & Vasconcelos, H. (2014). Anti-Competitive Impact of Pseudo-Generics. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 14(1), 83-98.

Saunders, M.N. and Lewis, P., (2012). Doing research in business & management: An essential guide to planning your project. Harlow: Pearson.

Song, C. H., & Han, J. W. (2016). Patent cliff and strategic switch: exploring strategic design possibilities in the pharmaceutical industry. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 692.

Stark, J. (2015). Product lifecycle management. In Product lifecycle management (Volume 1) (pp. 1-29). Springer, Cham.

Suri, F. K., & Banerji, A. (2016). Super Generics—First Step of Indian Pharmaceutical Industry in the Innovative Space in US Market. Journal of Health Management, 18(1), 161-171.

Voet, M. (2016). The generic challenge: understanding patents, FDA and pharmaceutical life-cycle management. Universal-Publishers.

Wagner, S., & Wakeman, S. (2016). What do patent-based measures tell us about product commercialization? Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry. Research Policy, 45(5), 1091-1102.