Written by Steve S.

Introduction

Contemporary organisations have to be innovative and constantly develop new products to remain competitive in the markets of their presence (Farid et al., 2017). Moreover, new products introduced by companies to their consumers should not only meet the needs and expectations of the target population, but also be affordable and cost-efficient. A number of factors such as resources available to an organisation, skills of the personnel, overall degree of rivalry in the market segment determine the success of newly launched products. In turn, theoretical and empirical literature on new product development (NPD) highlights that complex and intertwined factors predict NPD performance (Wu et al., 2016).

While employees working in research and development (R&D) teams of an organisation are primarily responsible for the development of new products, they also need to receive encouragement from their top leaders to be able to ‘think outside the box’, take proactive decisions and be truly innovative. Leadership encouragement has a potential to increase the pace of new product development, improve information-sharing processes and strengthen employee morale (Ren et al., 2015). Apart from internal ideas and resources, many successful organisations from technology and knowledge-intensive industries search for external NPD prompts from their customers, fans, independent researchers and even hackers (Schemmann et al., 2016). This approach, which is broadly known as crowdsourcing, is associated with many benefits for innovative companies. The aim of this critical essay is to examine how leadership encouragement and crowdsourcing influence new product development.

The Effect of Leadership Encouragement on NPD

The involvement of top organisational leaders in new product development can yield positive results if leaders realise their roles and are ready to remain constructive. In a qualitative study conducted by Dunne et al. (2016), the authors arrived at the conclusion that a leadership style, organisational efficacy, and the style of how negotiations were held had a direct impact on new product development. Dunne et al. (2016) also revealed that the encouragement by leaders contributed to speeding up the innovation process as well as the performance of newly launched products in the marketplace. On the downside, the qualitative nature of Dunne’s et al. (2016) research did not allow for deducing law-like generalisations and measurable cause-and-effect relationships between leadership engagement and innovation. Other researchers in the field are inclined to focus on the behavioural aspects of leadership encouragement and how they can stimulate new product development. In a study carried out by Nisula and Kianto (2018), leaders were said to contribute to NPD by developing the employees’ shared perceptions of the context of their work. This was achieved by motivating employees to reach their goals and offering tailored support in the form of skills training. It should be admitted that Nisula and Kianto’s (2018) research was limited to creative industries and may be criticised for generalisability issues.

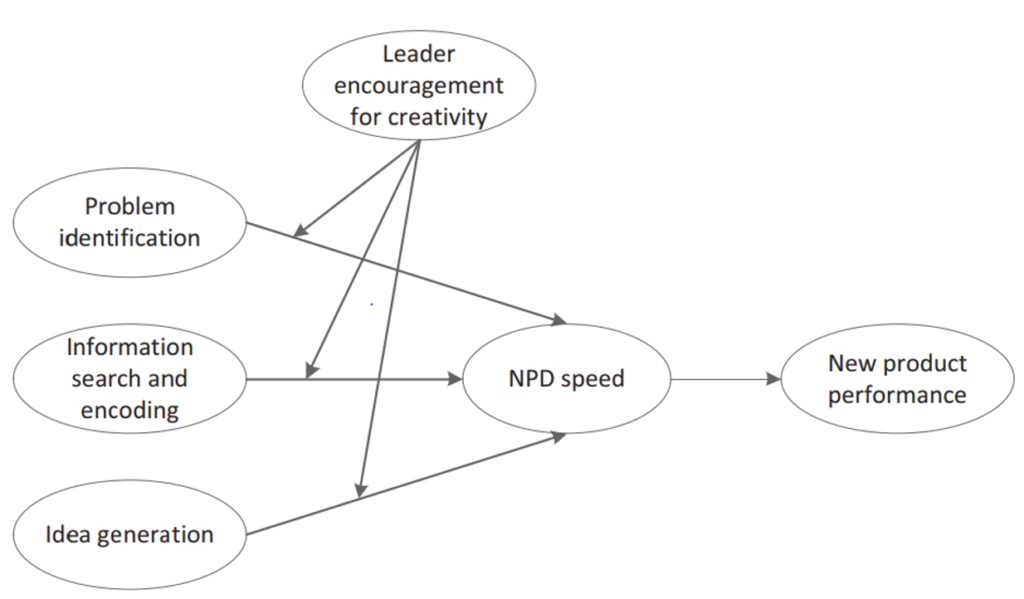

As it was noted earlier, organisations should seek to develop new products at a quicker pace to face competition adequately. This time requirement to new product development is conceptualised through the ‘NPD speed’ term that refers to the pace at which a new idea evolves from the conceptualisation stage to its final release and product launch (Chen et al., 2012). Cheng and Yang (2019) carried out empirical research that analysed the moderating role of leadership encouragement of creativity in the context of such constructs as NPD and NPD speed. To be more specific, the three consecutive stages of the NPD process were identified as problem identification, search for information and data encoding, and idea generation (Cheng and Yang, 2019).

A relatively large sample was approached by Cheng and Yang (2019), and the primary data was collected from 245 companies in China. The empirical research confirmed the moderating role of organisational leadership and the mediating role of innovation speed in stimulating NPR in the Chinese market. The applied structural equation modelling showed that leadership encouragement for creativity moderated the relationship between NPD speed and problem identification as well as the relationship between NPD speed and information search and encoding. The results obtained by Cheng and Yang (2019) emphasised the positive impact of leadership encouragement on developing and releasing innovative products at a higher pace. The findings also validated the hypothesised positive impact of NPD speed on new product performance. The researchers’ conceptual model is shown below in Figure 1. Despite these important insights gained from the study of Cheng and Yang (2019), one of its key limitations is the excessive reliance on primary data and full negligence of secondary evidence such as actual sales data, which can be used as a proxy for the success of new products (i.e. new product performan

ce). Arguably, secondary data can be more credible than primary data while dealing with such constructs as sales because researchers do not have any control over its collection and have to rely on its default credibility (Ellram and Tate, 2016).

Figure 1: The Moderating Role of Leadership Encouragement in the NPD Process

Source: Cheng and Yang (2019, p.215)

Many real organisations have benefited from leadership encouragement in their new product development process. For instance, Samsung’s top leadership is involved in the corporate NPD activities all the departments (Shaughnessy, 2013). The firm encourages its employees to develop innovative products that are viable and demanded in the potential outlet markets through their C-Lab programme. Under the C-Lab initiative, all organisational stakeholders can share suggestions regarding R&D that can be further converted into new products for different divisions of Samsung. Those teams who manage to design breakthrough concepts and prototypes receive managerial support and are provided with resources to streamline new product promotion. An open and participative leadership style adopted by Samsung has encouraged the product innovation at this company and helped it stay ahead of such competitors as Apple. These practical effects are highly consistent with what was discovered by Dunne et al. (2016). Samsung also helps its employees whose products are not ready for a launch to make them more viable and consistent (Samsung Newsroom, 2016). This enhances the company’s pool of ideas and stimulates an innovative culture.

The Effect of Crowdsourcing on NPD

Crowdsourcing has emerged as a source of NPD ideas for businesses around the world (Qin et al., 2016). It implies generating, sharing, and borrowing ideas from both internal and external crowds surrounding an organisation. Internal crowds include employees from all organisational departments who might not be even directly involved in current R&D activities. For example, employees from human resource and finance departments can be valuable for new ideas generation because of their unique perspective and specialised experiences. Alternatively, external crowds include customers, fans, independent researchers, and even competitors (Qin et al., 2016). Crowdsourcing is beneficial to profit-making organisations since it allows for refilling the in-house storage of ideas through multiple channels. On the other hand, crowdsourcing can be harmful for companies if they fail to organise effective crowdsourcing infrastructure. When shared in an open access, brilliant ideas can be quickly stolen by competitors, but it was the company who spent substantial resources on ideas attraction (Buchanan, 2018). Another negative outcome of crowdsourcing is that in-house R&D departments can become more relaxed and demonstrate less initiative.

The example of PepsiCo, which accepted interesting suggestions from its customers and launched ‘Cheesy Garlic Bread’ during the period of declining sales, shows that crowdsourcing is a reasonable solution at challenging times. As a result of this strategic initiative, the company’s sales grew by 8% (Buchanan, 2018). In addition, an attempt to crowdsource new product ideas also helps companies to control their costs because they do not need to pay external crowds for their suggestions (Brabham, 2017). Making crowds a part of the product development process has a positive impact on organisational reputation and allows for staying ahead of competitors. Nevertheless, crowdsourcing is not suitable for all NPD and R&D stages, and most companies attract crowds only for selected phases (e.g. product or package design, new product features, etc.) (Allen et al., 2018). The rest of the NPD process is delegated to internal teams and qualified professionals.

Having understood a high potential of crowdsourcing, many companies have gone online for attracting innovative ideas (Schemmann et al., 2016). Social media profiles of loyal customers and brand fans can be used effectively to start communication between brands and their followers, collect viable suggestions and run contests. An alternative channel is crowdsourcing online platforms such as Kaggle that allow companies to add a gamification element to new ideas generation and stimulate competition among their external crowds (Kaggle, 2019). A playful and competitive atmosphere positively contributes to overall creativity (Nisula and Kianto, 2018).

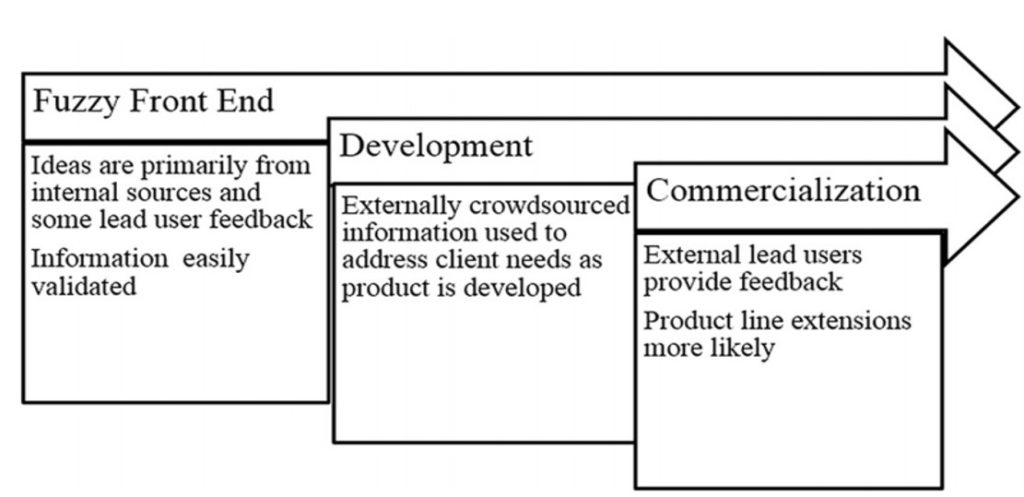

Recent empirical studies highlight the importance of crowdsourcing for new product and service development regardless of an industry or context. In a study conducted by Zahay et al. (2018), the authors presented evidence on the contribution of both internal and external crowds. The discussed research was qualitative in nature and was limited to the business-to-business (B2B) environment. The inputs gathered from internal sources were found to be useful in the front end of the NPD process. However, the inputs gathered from external sources were recognised as useful for introducing line extensions and minor improvements rather than for stimulating radical innovation (Zahay et al., 2018).

Interestingly, Zahay et al. (2018) pointed to the operational barriers associated with the limited utility of external sources. The application of crowdsourced ideas to the B2B environment is illustrated by the figure below. A major limitation of this study is that Zahay et al. (2018) failed to come up with appropriate suggestions regarding how to utilise the information gathered from external sources more effectively. Specifically, the role of crowdsourcing platforms could have been examined more carefully by these scholars (Kaggle, 2019). Further research aimed at both B2B and B2C contexts can address these gaps and re-evaluate the contribution of crowdsourcing to NPD.

Figure 2: The Application of Crowdsourcing Ideas to the B2B Environment

Source: Zahay et al. (2018, p.41)

An investigation conducted by Qin et al. (2016) focused on the key barriers to adopting crowdsourcing ideas in the course of the NPD process. This research took place in the context of the Chinese manufacturing sector. Qin et al. (2016) recommended that a higher degree of centralisation of the NPD process may increase the quality of innovative ideas attracted through crowdsourcing. In other words, external crowds should be timely informed about the current NPD objectives, resource availability, customer expectations and other parameters. This will help to make the innovation process more tailored and adjusted to organisational needs. Simultaneously, inflexible requirements can serve as a limitation and undermine creativity. One of the key strengths of Qin’s et al. (2016) research is that the scholars underlined the relevance of digital tools for more effective ideas collection.

A popular toy manufacturer LEGO has developed a crowdsourcing platform for its NPD purposes, which is broadly known as LEGO Ideas (LEGO, 2019). The uniqueness of this platform may be seen in a possibility for users to vote for ideas posted by other users. Ideas that have collected 10,000 and more votes are reviewed by the internal LEGO team and further recommended for a real launch (Buchanan, 2018).

Conclusion

In today’s challenging business environment, companies that offer products or services have to remain competitive through non-stop innovation and NPD. Even if it may be challenging for profit-making organisations to source fruitful and viable ideas from internal crowds, external crowds may serve as a good source of creativity and innovation. However, organsiations searching for NPD should firstly arrange well-thought infrastructure, effectively utilise social media and online crowdsourcing platforms, and take measures to avoid idea leaks to their competitors (Schemmann et al., 2016). Furthermore, it would be wise for organisational leaders to decide in the beginning which part of the NPD process they wish to delegate to customers, brand fans and external researchers (Allen et al., 2018). It is not recommended that the full cycle is outsourced. Leadership engagement has also been found to be essential for innovativeness and creativity. On the other hand, leaders should not apply autocratic and other power-intensive leadership styles because they potentially restrict creativity and freedom.

References

Allen, B.J., Chandrasekaran, D. and Basuroy, S. (2018) “Design crowdsourcing: The impact on new product performance of sourcing design solutions from the “crowd””, Journal of Marketing, 82 (2), pp. 106-123.

Brabham, D.C. (2017) The international encyclopedia of organizational communication, New York: Wiley.

Buchanan, G. (2018) “5 examples of companies innovating with crowdsourcing”, [online] Available at: https://blog.innocentive.com/2013/10/18/5-examples-of-companies-innovating-with-crowdsourcing [Accessed on 5 August 2019].

Chen, J., Reilly, R.R. and Lynn, G.S. (2012) “New product development speed: Too much of a good thing”, The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29 (2), pp. 288-303.

Cheng, C. and Yang, M. (2019) “Creative process engagement and new product performance: The role of new product development speed and leadership encouragement of creativity”, Journal of Business Research, 99 (1), pp. 215-225.

Dunne, T.C., Aaron, J.R., McDowell, W.C., Urban, D.J. and Geho, P.R. (2016) “The impact of leadership on small business innovativeness”, Journal of Business Research, 69 (11), pp. 4876-4881.

Ellram, L.M. and Tate, W.L. (2016) “The use of secondary data in purchasing and supply management (P/SM) research”, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 22 (4), pp. 250-254.

Farid, H., Hakimian, F., Ismail, M.N., and Nair, P.K. (2017) “Biotechnology firms-improvement in innovation speed”, International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 13 (2), pp. 167-180.

Kaggle (2019) “Kaggle competitions”, [online] Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions [Accessed on 8 August 2019].

LEGO (2019) “LEGO Ideas”, [online] Available at: https://ideas.lego.com/#all [Accessed on 8 August 2019].

Nisula, A. and Kianto, A. (2018) “Stimulating organisational creativity with theatrical improvisation”, Journal of Business Research, 85 (1), pp. 484-493.

Qin, S., Velde, D.V.D., Chatzakis, E. McStea, T. and Smith, N. (2016) “Exploring barriers and opportunities in adopting crowdsourcing based new product development in manufacturing SMEs”, Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 29 (6), pp. 1052-1066.

Ren, S., Eisingerich, A.B. and Tsai, H. (2015) “How do marketing, research and development capabilities, and degree of internationalization synergistically affect the innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? A panel data study of Chinese SMEs”, International Business Review, 24 (4), pp. 642-651.

Samsung Newsroom (2016) “How Samsung Helps its Internal Innovators to Spread their Wings”, [online] Available at: https://news.samsung.com/global/how-samsung-helps-its-internal-innovators-to-spread-their-wings [Accessed on 8 August 2019].

Schemmann, B., Herrmann, A.M., Chappin, M.M.H. and Heimeriks, G.J. (2016) “Crowdsourcing ideas: Involving ordinary users in the ideation phase of new product development”, Research Policy, 45 (6), pp. 1145-1154.

Shaughnessy, H. (2013) “What makes Samsung such an innovative company?”, [online] Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/haydnshaughnessy/2013/03/07/why-is-samsung-such-an-innovative-company/#5ccc98252ad7 [Accessed on 8 August 2019].

Wu, L., Liu, H., & Zhang, J. (2016) “Bricolage effects on new-product development speed and creativity: The moderating role of technological turbulence”, Journal of Business Research, 70 (1), pp. 127-135.

Zahay, D., Hajli, N. and Sihi, D. (2018) “Managerial perspectives on crowdsourcing in the new product development process”, Industrial Marketing Management, 71 (1), pp. 41-53.