Written by Steve S.

1. Introduction

The modern business environment is characterised by its ever-increasing instability and the necessity to constantly address the challenges posed by different crises (Farnese et al., 2016). Thus, organisational flexibility has to be properly governed in order to effectively and efficiently utilise all available resources and support the suggested change plan. Entrepreneurial leadership can be viewed as one of the ways to achieve positive results since leaders are proficient in recognising and taking advantage of opportunities as well as overcoming challenges and threats (Pisapia and Feit, 2015). The aim of this essay is to explore how entrepreneurial leadership can impact organisational flexibility during crisis periods.

2. Organisational Behaviour during Crises

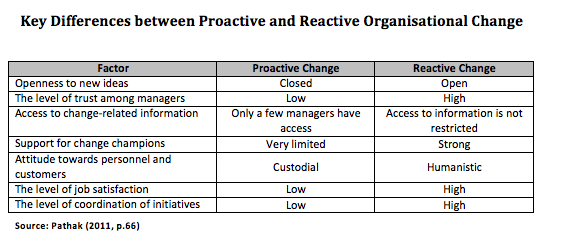

The need for organisational flexibility is substantiated by the growing instability of global economies and business environments (Farnese et al., 2016). In this situation, companies have to implement mechanisms and practices which are able to support their frequent transformational changes. Such activities can be both reactive or caused by external trends and proactive or caused by the internal strategic intentions of companies (Koryak et al., 2015). The main differences between these types of organisational change are summarised in the Appendix. While proactive changes have a considerable potential for the success of modern organisations, addressing crises frequently involves reactive changes. However, such adjustments should be made in advance if the enterprise can recognise the negative dynamics of the business environment and is capable of developing appropriate measures to prepare for the upcoming challenges (Shuria et al., 2016). Therefore, the role of adaptive management is critical at the present moment, which emphasises the significance of strategic leadership.

The discussed problem of crisis management can also be viewed within the scope of strategic flexibility and strategic adaptation (Pereira and Naguib, 2016). While organisations have to react to the changes in the external environment, their adaptation is limited by the availability of resources. As a result, the companies that cannot adapt to external changes during crisis periods incur substantial losses. Strategic management and entrepreneurship involve the choice of the general course that combines the strategic vision of the enterprise with objective market trends (Leitch and Volery, 2017). In turn, adaptation is used to adjust to some unexpected and minor changes. That said, the potential of governments and other regulators to assist businesses during crisis periods is limited by their conservative and reactive nature, which increases the significance of entrepreneurs (Moghaddam et al., 2015). This statement implies that flexibility effectiveness depends on the capability of business leaders to envision future trends and communicate the relevance of preparatory measures to all relevant organisational stakeholders.

Finally, the analysis of studies on crises by Bundy et al. (2016) revealed that both organisational and economic crises share four primary characteristics. Firstly, they result from change, uncertainty and disruption. Secondly, crises harm companies and their stakeholders. Thirdly, they are social phenomena that arise from the activities of various individuals in societies. Fourthly, they are a part of larger processes that may involve multiple organisations, industries and even countries (Bundy et al., 2016). While a large number of these factors cannot be controlled directly by individuals, the findings of Piorkowska (2016) suggested that organisational adaptability was directly associated with individual adaptability. Therefore, the capability of individuals to understand the changes and adapt to them directly influences organisational flexibility. The findings of Combe and Carrington (2015) indicated that entrepreneurial leadership could be highly effective in mitigating the impacts of crises if leaders were capable of understanding their causes and responding to them through employee motivation and the coordination of organisational resources.

3. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organisational Flexibility

Entrepreneurial leadership is the field of study that revolves around the role of leadership in the organisational environment (Leitch and Volery, 2017). Leaders are viewed as individuals who collect resources from different stakeholders and organise them in the most optimal way to address changes in the external context (Farnese et al., 2016). These qualities make leadership highly relevant during crisis periods. The positive impact of such practices is associated with the fact that organisational effectiveness is based on several types of resources such as human resources and financial resources (Koryak et al., 2015). The motivational effect of leadership can increase employees’ outputs, which positively impacts the utilisation of other assets and stimulates the development of organisational knowledge and competences. That said, the results depend on the qualities and experience of the leader and his or her capability to recognise and capitalise on the opportunities existing in the business environment (Leitch and Volery, 2017).

Entrepreneurial leadership is usually viewed as a combination of five core practices, namely proactiveness, risk-taking, innovativeness, autonomy and aggressive competitiveness (Zehir et al., 2015). These elements are associated with supporting changes to withstand competition and achieve sustainable competitive advantage. In their study, Pisapia and Feit (2015) linked entrepreneurial leadership with three elements, namely the presence of opportunity in the environment, the capability of entrepreneurs to recognise it and their ability to coordinate resources to respond to this opportunity. These qualities are highly applicable to crisis conditions as well since leaders need to predict them and find the ways to deal with them while achieving the best possible outcome. At the same time, Anyanwu and Oad (2016) argued that the access to resources necessary for addressing the arising problems directly depended on the qualities of the leader. As these assets are obtained from various stakeholders, leaders’ capability to convince their followers and promote the proposed plan of action is critical for gaining the material elements required for the implementation of crisis management measures. Hence, it is impossible to achieve high levels of organisational flexibility without the access to resources acquired by utilising the reputation and perceived reliability of entrepreneurial leaders.

It can be summarised that entrepreneurial leadership influences organisational flexibility through its strategic, motivational, communicative and personal dimensions (Jawi and Izhar, 2016). Entrepreneurs communicate their crisis management vision to stakeholders, motivate their followers, develop strategic change measures and rely on their internal qualities to achieve these results. At the same time, DuBrin (2015) argued that contemporary leaders had to accept adaptability and flexibility as one of the most relevant qualities. This need is justified by the ongoing changes in the external environment and the necessity to lead organisations and followers through these changes. Therefore, the leaders who are prepared for this challenge can make their company substantially more effective and competitive during crisis periods (Gavinelli, 2016).

4. Examples of Entrepreneurial Leadership Impact on Organisational Flexibility

The relevance of entrepreneurial leadership during the Global Financial Crisis was noted by IBM (Uhl-Bien et al., 2017). The representative of the company stated that gradual small changes were no longer an option for modern companies that had to quickly adapt to turbulent environments. Therefore, leadership was suggested as one of the key practices capable of reducing complexity during crisis periods by connecting different organisational dimensions and elements to create a uniform adaptive response (Uhl-Bien et al., 2017). The relevance of entrepreneurial leaders for the management of external turbulence is supported by the example of another leader, namely the CEO of the Euro Pacific Capital organisation who predicted the 2008 financial downturn a year ahead of it (Mastrangelo, 2015). These findings are in line with Pisapia and Feit (2015) who stated that leadership was associated with the capability to recognise opportunities and threats in the macro-environment. However, the negative impact of this crisis on the majority of organisations suggests that their leaders could possess the vision but lacked the communicative skills necessary to develop a change plan and organise the resources necessary for its proactive implementation (Hetfield and Britton, 2016).

Another example of the positive entrepreneurial leadership impact on organisational flexibility is the survival of Xerox during the industry-level and company-level crisis in the 2000s (Hodges and Gill, 2014). The newly appointed CEO, Anne Mulcahy, quickly formed a leadership team and increased the net earnings of the firm up to $1.2 billion within 5 years while reducing the number of employees from 91,000 to 58,000 (Hodges and Gill, 2014). This strategic transformational change addressing the negative external and internal factors can be viewed as an example of outstanding flexibility and adaptability that allowed Xerox to overcome the crisis. That said, the aforementioned leadership team also demonstrated the communicative and organisational skills mentioned by Leitch and Volery (2017) and Pereira and Naguib (2016) as they motivated several key executives to stay with the company while simultaneously obtaining the necessary resources from multiple investors (Hetfield and Britton, 2016).

5. Conclusion

It can be concluded that some elements of entrepreneurial leadership, namely the capability to recognise threats and opportunities, mobilise resources and respond to these factors can be successfully applied to crisis management in organisations (Pisapia and Feit, 2015). The outcomes of these practices directly depend on the personal qualities and skills of a leader as the resulting flexibility would be largely determined by the scope of mobilised assets. This fact makes the communicative abilities of leaders especially important (Anyanwu and Oad, 2016). At the same time, the positive experience of modern companies such as Xerox demonstrates that entrepreneurial leadership may be a necessity for them to mitigate the negative effects of crises (Combe and Carrington, 2015; Hetfield and Britton, 2016).

References

Anyanwu, C. and Oad, S. (2016) “Entrepreneurial leadership and organizational creativity in the collectivist context: The moderating role of emotional intelligence”, International Journal of Management and Administrative Sciences, 4 (2), pp. 1-12.

Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M., Short, C. and Coombs, W. (2016) “Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development”, Journal of Management, 1 (1), pp. 1-32.

Combe, I. and Carrington, D. (2015) “Leaders’ sensemaking under crises: Emerging cognitive consensus over time within management teams”, The Leadership Quarterly, 26 (3), pp. 307-322.

DuBrin, A. (2015) Leadership: Research findings, practice, and skills, New York: Nelson Education.

Farnese, M., Fida, R. and Livi, S. (2016) “Reflexivity and flexibility: Complementary routes to innovation?”, Journal of Management & Organization, 22 (3), pp. 404-419.

Gavinelli, L. (2016) Business Strategies and Competitiveness in Times of Crisis: A Survey on Italian SMEs, Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Hetfield, L. and Britton, D. (2016) Junctures in Women’s Leadership: Business, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Hodges, J. and Gill, R. (2014) Sustaining change in organizations, London: SAGE.

Jawi, A. and Izhar, T. (2016) “Recent Development on Entrepreneurial Leadership Capabilities and Innovativeness in Academic Libraries: A Review and Directions for Future Research”, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6 (1), pp. 40-54.

Koryak, O., Mole, K., Lockett, A., Hayton, J., Ucbasaran, D. and Hodgkinson, G. (2015) “Entrepreneurial leadership, capabilities and firm growth”, International Small Business Journal, 33 (1), pp. 89-105.

Leitch, C. and Volery, T. (2017) “Entrepreneurial leadership: Insights and directions”, International Small Business Journal, 35 (2), pp. 147-156.

Mastrangelo, A. (2015) Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Practical Guide to Generating New Business: A Practical Guide to Generating New Business, London: ABC-CLIO.

Moghaddam, J., Khorakian, A. and Maharati, Y. (2015) “Organizational entrepreneurship and its impact on the performance of governmental organizations in the City of Mashhad”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 169 (1), pp. 75-87.

Pathak, H. (2011) Organisational change, Chennai: Pearson Education.

Pereira, R. and Naguib, O. (2016) “Strategic entrepreneurship and dynamic flexibility: Towards an integrative framework”, International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 5 (4), pp. 307-312.

Piorkowska, K. (2016) “Behavioural strategy: Adaptability context”, Management, 20 (1), pp. 256-276.

Pisapia, J. and Feit, K. (2015) “Entrepreneurial Leadership at a Crossroads”, DIEM, 2 (1), pp. 524-533.

Shuria, H., Linge, T. and Kiriri, P. (2016) “The Influence of Organizational Flexibility on Humanitarian Aid Delivery Effectiveness in Humanitarian Organizations in Somalia”, International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences, 3 (4), pp. 72-89.

Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R. and McKelvey, B. (2017) “Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era”, The Leadership Quarterly, 18 (4), pp. 298-318.

Zehir, C., Can, E. and Karaboga, T. (2015) “Linking entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The role of differentiation strategy and innovation performance”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences