Written by Katy J.

1. Introduction

In the last several decades, globally recognised and established brands have been demonstrating growing interest in new global markets including those of developing countries (Riley et al., 2016). While these environments are associated with substantial customer resources, the entry into them is often hindered by various economic, political or cultural barriers. The need to adjust to the particularities of each country of presence often forces global brands to adhere to ‘glocalisation’ strategies that combine the core elements of their international positioning with localised positioning concepts to improve the effectiveness of marketing communication (Parsons and Maclaran, 2017). However, the substantiation of such choices may be complicated and companies’ market entry decisions often have to be studied on a case-by-case basis. The aim of this essay is to explore the key reasons why global brands adopt different positioning strategies in the countries of their presence.

2. Country-Specific Positioning Problems

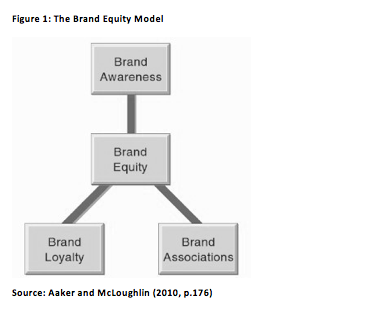

In accordance with the brand equity model offered by Aaker and McLoughlin (2010), brand associations are among the most valuable assets, which help companies create formidable competitive advantages.

Positive and unique brand associations in consumer minds are usually created with the help of a set of marketing practices, which are commonly referred to as positioning (Jansson-Boyd and Zawisza, 2016). These practices explain why the promoted brand is different from and better than its competitors (Sair, 2014). One of the most problematic aspects of these activities is the existence of two perspectives, namely the company perspective and customer perspective. While the enterprise has the vision of a product or service determined by pre-production marketing analyses, end clients may form their own perceptions defined by their brand expectations and individual preferences (Steenkamp, 2017). Hence, the wrong choice of positioning strategies can negatively affect brand images and avert customers from the promoted products. Individual consumption patterns may also stem from demographical and cultural backgrounds (Seo and Buchanan-Oliver, 2015). Specifically, US consumers of luxury brands are generally younger than their counterparts in developing countries and demonstrate lower brand loyalty and higher willingness to experiment with multiple brands (Lysonski, 2014). Another example is the Chinese market where some brands are unsuccessful due to the fact that the counterfeit products imitating these brands are so popular that original products are also viewed as counterfeits and do not create the desired effect of elitist consumption (Prange, 2016).

The need to adopt different positioning strategies is largely dictated by the cultural, political and economic diversity of various countries (Jansson-Boyd and Zawisza, 2016). These differences may be substantiated by the fact that targeted consumer groups have unique national, individual and demographic characteristics. According to Malik and Sudhakar (2014), these characteristics determine consumers’ information reception patterns and may affect their perceptions of global brands. While some positioning conflicts may be difficult to resolve, a lot of situations can be addressed by ‘adjusting’ the advertising materials and promoted brand image to the cultural patterns of the country of presence (Seo and Buchanan-Oliver, 2015). By doing that, organisations are able to ensure that their brand message is correctly conveyed using the marketing ‘language’ of the targeted customer group. These aspects are especially significant for emerging markets (Khan, 2014). While these environments are characterised by a rapid economic growth during the last decades, they also have substantial regulatory, infrastructural and communication barriers. In developing countries, western brands may be attractive to wealthy consumers seeking higher life standards rather than mass market customers who require a different positioning strategy (Malik and Sudhakar, 2014). At the same time, insufficient Internet technology development often explains the greater effectiveness of television and printed press and requires an adjustment of marketing strategies.

The analysis of US companies’ operations in China by Lysonski (2014) identified that only three factors had a positive impact on consumer decisions to purchase specific brands. Firstly, social demonstration effect was relevant to consumers as the consumption of globally recognised and established products was viewed as a way to demonstrate individual superiority. Secondly, brand relevance was important as Chinese customers were generally sensitive to brand power and preferred to purchase more ‘powerful’ brands rather than experimenting with new ones (Lysonski, 2014). Thirdly, reference group influence was important for being able to associate oneself with the desired image through ‘consuming’ the items symbolising this image (Chinaka, 2016). All of these elements were relevant to Chinese consumers due to the fact that the country had a collectivist society and consumption patterns were largely dictated by the need to fit in and compare oneself with larger social groups (Lysonski, 2014). On the contrary, the incentives relevant to US buyers were generally ineffective in the context of China.

International organisations have to retain the elements of global positioning that define them as established and iconic brands while incorporating a ‘local’ component by choosing the most relevant communication channels, advertising concepts and cultural images that appeal to the targeted customers (Heinberg et al., 2017). The problem is also associated with the source credibility issue, as global promotion through internationally recognised media may not have equal effectiveness compared to the local positioning instruments that are necessary for creating customer awareness in specific regions. Celebrity endorsement is one of the methods that allow for resolving this controversy (Malik and Sudhakar, 2014). As famous individuals are generally recognised by consumers as influence agents, marketing communication messages delivered by them are viewed as more reliable. Therefore, it can be summarised that different positioning may be necessary due to the uniqueness of various contexts and customer segments that is defined by their political, cultural and economic backgrounds.

3. The Behaviour of Global Brands in Their Countries of Presence

Such brands as Coca-Cola and P&G have traditionally utilised the ‘power brand’ expansion strategy by relying on global advertising and uniform positioning (Hu et al., 2016). On the contrary, Unilever and Nestle have adopted a different approach to the promotion of their brands in international markets. These companies take into account the cultural uniqueness of each country and mix globally distributed products with the products of acquired local brands (Parsons and Maclaran, 2017). Similar strategies are adopted by the Danone brand. For example, this company combines its global positioning as a healthy food supplier with the need to fit the Chinese biscuit, milk and beverages market (Prange, 2016). Danone combines its image as a French origin company with local consumption trends and food preferences, which have a positive impact on the targeted consumers.

Another positioning issue experienced by Coca-Cola, Unilever and Samsung in China and some other Asian countries is the need to translate and transliterate brand names (Steenkamp, 2017). On the one hand, companies can select an appropriate designation in the target language with positive cultural connotations. On the other hand, it is possible to purchase local brand names that have no reference to the global company (Parsons and Maclaran, 2017). In many cases, the original logo or branding elements may have negative connotations in the country of interest or convey a different meaning that is not conceived by the organisation. For example, Coca-Cola customers in Nigeria are generally unaware about the foreign origin of Fanta, Coke and Sprite beverages as they are sold under local brands (Otuedon, 2016). Adaptive positioning is also utilised by the McDonald’s company that operates globally through franchisee agreements. This organisation combines the global positioning of the brand as a high-quality provider of fast-food products with localised elements represented by country-specific menu items (Parsons and Maclaran, 2017).

One of the techniques used by global brands for positioning purposes is the support of sports events in their countries of interest (Mikacova and Gavlakova, 2014). While a certain degree of localisation is sought due to the reasons discussed earlier by Heinberg et al. (2017), it is often difficult to find an effective communication channel that emphasises the international image of the company while focusing on local elements. The sponsoring of sports events is a highly effective method of resolving this controversy that allows global brands such as Coca-Cola to achieve hybrid positioning (Dissanayake and Amarasuriya, 2015). Another example of the issues mentioned by Khan (2014) is the marketing representation of Apple and Samsung in different countries. The former has a focused and ‘globalised’ positioning as a premium brand appealing to the segment of wealthy customers who want to demonstrate their individual superiority through owning items from a ‘powerful brand’. On the contrary, Samsung products are purchased by a wide variety of individuals, which complicates the positioning and frequently requires the substantial ‘glocalisation’ of promotional activities to appeal to individual customer groups in the countries of interest (Dissanayake and Amarasuriya, 2015).

4. Conclusion

Global organisations have to adopt different positioning strategies in their countries of presence due to the cultural, political and economic diversity of these contexts, which create a discrepancy between these firms’ global image and the perceptions of local customers (Jansson-Boyd and Zawisza, 2016). However, this adjustment is not compulsory for all brands as some premium products can be marketed without substantial adaptation (Dissanayake and Amarasuriya, 2015; Hu et al., 2016). The differences between cultural perceptions and language connotations may force globally recognised companies to change their positioning approaches or operate through acquired local brands separated from their global brand (Steenkamp, 2017). Hence, the choice of the adaptation strategy depends on a particular situation and the targeted consumer group.

References

Aaker, D. and McLoughlin, D. (2010) Strategic Market Management: Global Perspectives, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Chinaka, N. (2016) “Factors that influence consumer purchasing behavior in Nigeria”, The International Journal of Business & Management, 4 (4), pp. 157-161.

Dissanayake, D. and Amarasuriya, T. (2015) “Role of brand identity in developing global brands: A literature based review on case comparison between Apple iPhone vs Samsung smartphone brands”, Research Journal of Business and Management, 2 (3), pp. 430-440.

Heinberg, M., Ozkaya, H. and Taube, M. (2017) “The influence of global and local iconic brand positioning on advertising persuasion in an emerging market setting”, Journal of International Business Studies, 1 (1), pp. 1-14.

Hu, Z., Chen, X. and Yang, Z. (2016) Research Frontiers on the International Marketing Strategies of Chinese Brands, London: Routledge.

Jansson-Boyd, C. and Zawisza, M. (2016) Routledge International Handbook of Consumer Psychology, London: Taylor & Francis.

Khan, M. (2014) “Challenges for MNEs Operating in Emerging Markets”, Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 18 (1), pp. 1-16.

Lysonski, S. (2014) “Receptivity of young Chinese to American and global brands: Psychological underpinnings”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31 (4), pp. 250-262.

Malik, A. and Sudhakar, B. (2014) “Brand positioning through celebrity Endorsement - A review contribution to brand literature”, International Review of Management and Marketing, 4 (4), pp. 259-275.

Mikacova, L. and Gavlakova, P. (2014) “The role of public relations in branding”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110 (1), pp. 832-840.

Otuedon, M. (2016) “The Role of Creativity in the Market Segmentation Process: The Benefits of Having an Excellent Global Brand Positioning”, International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 4 (2), pp. 295-314.

Parsons, E. and Maclaran, P. (2017) Contemporary issues in marketing and consumer behaviour, London: Routledge.

Prange, C. (2016) Market Entry in China: Case Studies on Strategy, Marketing, and Branding, Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Riley, F., Singh, J. and Blankson, C. (2016) The Routledge companion to contemporary brand management, London: Routledge.

Sair, S. (2014) “Consumer Psyche and Positioning Strategies”, Pakistan Journal of Commerce & Social Sciences, 8 (1), pp. 58-73.

Seo, Y. and Buchanan-Oliver, M. (2015) “Luxury branding: the industry, trends, and future conceptualisations”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 27 (1), pp. 82-98.

Steenkamp, J. (2017) Global Brand Strategy: World-wise Marketing in the Age of Branding, Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.