Written by Josh A.

Abstract

The current research project aims to investigate into the relationship between the social media presence and brand trust of Cadbury, a UK-based confectionary company. Primary quantitative data is obtained to achieve this aim. It is established that Cadbury relies on robust social media presence including a variety of channels (e.g. Facebook and Twitter) as well as on different engagement strategies such as purely promotional messages and direct customer interactions. However, these marketing efforts were insufficient to achieve a consistently high level of brand trust in the company’s online communities. Social media training as well as content marketing are recommended for Cadbury as possible solutions to this problem.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

Social media marketing proves to be a powerful promotional tool available to modern business organisations due to their wide reach and high interactivity potential. It is proposed that social media can be leveraged to improve a company’s position with respect to the major marketing factors such as brand equity or consumer behaviour (Hyder, 2016). At the same time, user-generated content plays a vital role in the context of social media, which can affect consumer trust and reactions without any input from a company (Ozuem and Bowen, 2016). Another issue is that social media allows customers to communicate directly with the company representatives, and this may complicate the process of building consumer relations and creating trust (Shih, 2016). These obstacles raise a problem of what exactly has to be done by businesses in order to improve the level of trust exhibited by the end consumers influenced by the social media presence of these companies. The outlined problem is critically evaluated and reviewed in this dissertation.

1.2. Focus and Background of the Study

Cadbury is chosen as the focal point for the current research project. One of the factors supporting this choice is that Cadbury is a billion-dollar brand (Mondelez International, 2016). This means that the organisation has to maintain its marketing communications by relying on a wide variety of channels (including social media) and with respect to a diverse customer base (Mondelez International, 2016). For instance, Cadbury maintains a strong presence on Twitter and Facebook, exemplifying a multi-channel approach (Link Humans, 2017). Another reason for investigating into Cadbury’s business is that the company faces a substantial threat from its competitor such as Nestle (Focus on Pigments, 2015; Brook, 2017). In these conditions, marketing should be crucial for Cadbury to gain consumer trust, thus augmenting its competitive position. On the other hand, it is acknowledged that the findings related to Cadbury may not be necessarily applicable to other companies in the confectionary industry (Given, 2015).

1.3. Research Aims and Objectives

The main research aim of this dissertation is to analyse how the social media presence of Cadbury influences brand trust among the online community members on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

- To examine how brand trust contributes to the overall brand equity.

- To evaluate the degree to which Cadbury is presented on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

- To analyse the impact of Cadbury’s social media presence on customers’ trust perceptions.

- To develop practical recommendations for Cadbury as how to build online trust more effectively.

1.4. Structure of the Study

The dissertation is divided into five chapters. Chapter 2 presents a detailed review of the existing body of knowledge concerning social media and brand trust. The methodological set of the study is explained in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 highlights the key findings of the project and provides a discussion comparing these outcomes to what was stated by other authors. Chapter 5 summarises the results of the study and accounts for its limitations.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1. Brand Trust as a Constituent of Brand Equity and Key Measurements of Trust

It is essential to review the position of brand trust among the broader frameworks of brand equity. According to Aaker (1992), brand trust stands for the positive feelings evoked by a particular brand and is therefore a part of brand associations. At the same time, the perspective suggested by Aaker (1992) is criticised for excessively focusing on the market outcomes. This model can be complemented by relying on a more customer-centric interpretation.

As shown above, Keller (2015) proposed that brand equity could be conceptualised as customer reactions along the dimensions of identity, meaning, response and relationships. In turn, Keller’s (2015) definition entailed that brand trust was an overreaching concept transmitted by the companies and received by the customers at all levels of brand equity. Since the paradigm of Keller (2015) includes the major customer-related factors, this doctrine is employed by the study.

The key theoretical postulates developed by Keller (2015) were supported in the recent empirical works on the subject of branding. Specifically, Japutra and Molinillo (2017) provided strong evidence in favour of the fact that the projected personality of brands (in particular, perceived levels of activity and responsibility) had a significant impact on the end consumers’ attitudes related to trust. A similar point was made by Rubio et al. (2017) who asserted that the meanings attached to a brand by the brand holding company directly affected the opinions and perceptions of the target market segments in terms of trust and buying behaviour (Rubio et al., 2017). On the other hand, the key limitation of the above findings was that unavoidable noise could distort the marketing messages distributed by companies, which could negatively affect the levels of trust exhibited towards brands when no objective reasons for this effect were present (Kotler and Armstrong, 2014). It would be interesting to observe whether this discrepancy can influence the results of the present study.

Turning now to customer responses, it can be stated that the means and platforms facilitating the interaction between customers and brands can have a vital influence on brand trust. This was confirmed in the case of online platforms by Phua et al. (2017) who noted that different social media platforms (i.e. Instagram and Twitter) encouraged varying reactions from their users. For example, Twitter users valued brand membership community identification, while Instagram was positively evaluated in terms of brand engagement (Phua et al., 2017). These arguments were further reinforced by Lin et al. (2017). These authors posited that among online community members, the responses related to community cohesiveness and information quality had a direct effect on the dimensions of brand equity (Lin et al., 2017). However, it is admitted that neither Phua et al. (2017), nor Lin et al. (2017) focused on the food industry. It is ultimately ambiguous whether Cadbury’s customers will follow similar rules to those established in these works.

As for brand relationships, the last constituent of Keller’s (2015) scheme, it was asserted by Giovanis and Athanasopoulou (2017) that the concepts of brand loyalty, brand trust, brand satisfaction and brand commitment were connected causally when business entities made a conscious effort to maintain long-term communications with their customers. Nonetheless, these associations may not be true with respect to online communities. Martinez-Lopez et al. (2017) reinforced this statement by arguing that the participation in community-related events as well as the behaviour of other community members could have a significant impact on brand trust and other components of brand equity. An important implication of this observation is that it can be challenging for organisations to fully control all factors influencing brand trust in the context of online platforms.

The following table summarises the main theoretical discussions presented in this section and details the key units for the subsequent analysis.

2.2. Main Strategies of Social Media Presence: Applicability to Cadbury

It is also relevant to refer to the main types of social media marketing and presence. According to Rawat and Divekar (2014) and Jung (2017), social media presence is typically construed of the social media platforms an organisation has an account on as well as of the types of content posted on these websites. In the case of Cadbury, Facebook and Twitter are recognised as the key instruments of social media presence preferred by the company (Link Humans, 2017). At the same time, social media presence was evaluated as a sum of company-generated messages and consumer engagement by Osei-Frimpong and McLean (2017), which is in conflict with the organisation-centric perspective offered by Rawat and Divekar (2014). Thus, it is necessary to evaluate both dimensions in detail.

One possible solution would be to employ the categorisation designed by Alalwan et al. (2017) who claimed that the information related to the social media presence of a firm could include purely advertising subjects (e.g. promotional information about product features) as well as communicating directly to the end customer (Lee and Hong, 2016). Notably, Cadbury relies on both approaches by showcasing its value offerings and also responding to the comments left by customers (Link Humans, 2017). However, as proposed by Felix et al. (2017), social media investigations can be carried out through a purely organisational perspective. For instance, a conservative attitude towards social media entailed that digital marketing was only viewed as a standard means of transmitting advertising messages, while modernism was exhibited by firms that utilised the full capacity of these platforms, including interactive communication with the end consumers (Felix et al., 2017). Since the present study adopts a customer-centric perspective, the point of view exhibited by Felix et al. (2017) is not employed in further analysis.

Additional rationale to the above ideas was given by Wang and Kim (2017), as these scholars discussed evidence showing that social media could enhance the customer relationship management (CRM) activities of a firm (Harrigan et al., 2015). For instance, talking directly to the end consumers through social media platforms could enhance brand trust. In theory, Cadbury exemplifies this by regularly responding to customer feedback and comments (Link Humans, 2017). It was also revealed that CRM was dependent on the highly subjective reactions of the end consumers, making this particular element of Cadbury’s social media presence risky (Wang and Kim, 2017; Felix et al., 2017). A similar idea was expressed by Agnihotri et al. (2017) who observed that companies had to be ready to account for unpredictable consumer behaviour on social media across the channels where their presence was established (Agnihotri et al., 2017). The outlined results are interpreted as evidence that the effectiveness of social media presence in terms of building brand trust may be limited (Agnihotri et al., 2017).

Turning to other forms of maintaining social media presence, the importance of user-generated content was highlighted by Geurin and Burch (2016). Specifically, it was shown that user-created posts on social media could generate higher levels of brand trust than the messages left by the company itself (Geurin and Burch, 2016). This practice was followed by Cadbury as the firm encouraged its customers to openly display their opinions of Cadbury’s offerings using company-related hashtags on Twitter and Facebook (Link Humans, 2017). However, since user-generated information was not controlled by most businesses, this element of social media presence introduced noteworthy contingencies. Balaji et al. (2016) exemplified this by explaining that negative e-WOM could be a significant influence on the opinions of other customers involved in social media communication. It would be reasonable to apply the above results to the empirical case of Cadbury to determine which specific strategies were applied by the organisation and how the firm attempted to avoid the mentioned challenges.

2.3. Framework of the Study

The next figure graphically summarises the contents of Chapter 2 and provides a framework for the subsequent analysis of the data focused on Cadbury. The key empirical observations obtained from the model of Keller (2015) were employed as the approximations of Cadbury’s brand trust.

In addition, the following hypotheses are developed to represent the most interesting relationships identified in the framework.

H1: Consistent direct customer communications increase brand trust.

H2: Encouraging user-generated content has a positive effect on brand trust.

H3: Purely advertising messages are unable to raise brand trust.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1. Research Philosophy and Approach

Having started with theory, this chapter discusses the key methodological principles at the core of the present investigation. According to Saunders et al. (2015), there exists a choice between epistemology, ontology and axiology in business research. Epistemology is chosen for the dissertation as this paradigm focuses on the relationship between the researcher and the subject matter, while ontology and axiology are more concerned with the fundamental nature of reality and the role of values respectively (Lyon, 2016). As for the philosophical stances, positivism, which is fundamentally similar to natural sciences research, is employed in the dissertation (Pernecky, 2016). Simultaneously, it is acknowledged that since positivism is suitable to interpreting objective facts, its explanatory power is limited whenever subjective and unpredictable human behaviours and opinions are concerned. This view is relevant to the present study due to its focus on the attitudes of the end customers (Saunders et al., 2015).

3.2. Research Approach, Data Collection and Analysis

The project follows the principles of deductive logical reasoning by verifying the validity of the theoretical suggestions made in Chapter 2 using the collected primary data (Goranko, 2016). However, deduction is limited by the frameworks and findings mentioned by other authors, thus constraining the amount of the contribution made by this dissertation to the existing body of knowledge in the fields of brand trust and social media presence (Foresman et al., 2016). Only primary quantitative evidence is gathered for this study through a self-administered questionnaire survey among the customers of Cadbury (Creswell, 2014; Teater et al., 2017). The most substantial benefit offered by this method of data collection is that self-administered questionnaires are easy to distribute among the target population and the study participants are free to complete the forms whenever it is convenient (Bryman, 2016). Nonetheless, the researcher is unable to posit any additional questions or clarify the specific questionnaire items to the target respondents (Bryman, 2016). The questionnaire forms (Appendix A) were sent out to more than 200 individuals online, but only 73 customers of Cadbury completed them and returned to the researcher.

In terms of sampling, the non-probability convenience sampling method was employed by this study (McDaniel and Gates, 2016; Schutt, 2016). It is admitted that it is impossible to make statistical generalisations on the basis of this sample, which significantly limits the whole study in terms of expanding its findings to the overall UK population (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). Both graphical and statistical analysis techniques are utilised by the dissertation to achieve the designated research objectives. The Likert scale is integrated into the questionnaire responses (see Appendix A) to facilitate the process of evidence interpretation (Finch et al., 2016). The linear regression model is constructed to establish any causal relationships between the previously identified research variables (Darlington and Hayes, 2017). While descriptive statistics (e.g. medians and means) could be implemented to measure the social media presence of Cadbury as well as the level of brand trust exhibited by the end consumers, these techniques would be insufficient to confirm or reject the outlined research hypotheses (see Section 2.3).

3.3. Definition of Research Variables

The following table briefly defines the key research variables for the statistical analysis and assigns specific questionnaire items to them (see Appendix A).

Neither the social media platforms used by Cadbury, nor the behaviours of other community members are included in the linear regression model. The presence on social media platforms is measured via a multiple-choice question (Question 3), while online community members’ behaviours (Question 10) are a highly subjective indicator. The three linear regression models are as follows.

PRI, ENG and IDE correspond to the projected image of Cadbury, the degree of user engagement and community identification respectively, α0 is a constant, β1, 2, 3 are indicators that influence the independent variables, namely ADV, DCC and UGC (i=1, 2, 3…73) and ε stands for residuals.

3.4. Research Ethics

To protect the rights and interests of the human participants in this study, full anonymity is provided by the research project (Pruzan, 2016). Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from the representatives of the sample (van den Hoonard and van den Hoonard, 2016). The research also allowed the participants to cancel their involvement in the project at any time.

Chapter 4: Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample: Demographics and Social Media Following

It is necessary to briefly appraise the characteristics of the sample related to their demographics and the key social media platforms on which these individuals followed Cadbury (Questions 1-3 in the Questionnaire, see Appendix A). As indicated in Appendix B, 43.8% and 53.4% of the sample were males and females respectively. The key implication of this is that the study gathered the perceptions and opinions of a diverse population. This is further supported by the fact that the participants represented different age groups. For instance, 35.6% of the sample attributed themselves to the ‘21-34’ age group, while 31.5% were older than 35, but younger than 50. This composition of the sample is highly beneficial in terms of results validity and reliability (Gray, 2016). However, it is unknown whether the sample reflected objectively the perceptions and attitudes of mainstream customers of Cadbury in the UK, which limits the contribution made by the dissertation (O’Sullivan et al., 2017).

The next figure accounts for the most popular social media platforms among the study participants.

It is observed that Twitter was the most significant social medium with 69.9% of the sample selecting this answer. Facebook (58.9%) and Instagram (39.7%) were also highlighted by the study participants (each participant could select more than one response option). In turn, Google+ and YouTube were only mentioned by 23.9% of the sample each. These results are consistent with the overview provided by Link Humans (2017), which stated that the most prominent areas of Cadbury’s social media activity were concentrated on Twitter and Facebook. To summarise, the above responses effectively limit the findings of this study to three social media platforms, meaning that the recommendations developed for Cadbury in the following chapter could only apply to Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

4.2. The Social Media Presence of Cadbury

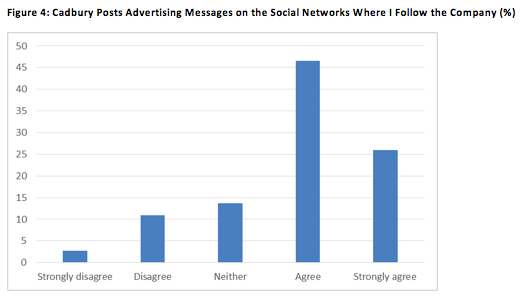

This section of Chapter 4 refers to the attitudes held by the sample with respect to the established manifestations of the social media presence of Cadbury. The next bar chart illustrates the evidence obtained for the dimension of advertising.

Figure 4 shows that the total of 72.6% of the surveyed population either agreed or strongly agreed with the fact that Cadbury posted purely advertising messages on its social media. This is consistent with what was argued by Lee and Hong (2016) regarding the importance of promotional messages on such channels as Twitter and Facebook. In other words, informing the end consumers about the benefits of the firm’s products was one of the key methods of building and maintaining Cadbury’s strong social media presence. At the same time, this does not mean that the company focused purely on this aspect of social media communications. As illustrated in Appendix B, as much as 78% of the sample chose the response options ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ when evaluating Cadbury’s direct communication efforts. Therefore, it can be stated that Cadbury also employs interactive dialogues with the end consumers to further reinforce the strength of its social media efforts. A similar point can be made with regards to the user-generated content focused on Cadbury (Appendix B). One critical remark that can be raised against the outlined points is that the study did not identify any objective appraisals of the social media presence of Cadbury. The perspective offered by the sample representatives may be highly subjective and fail to reflect Cadbury’s real social media endeavours.

4.3. Cadbury’s Brand Trust: Key Measurements and Relationships

It was asserted in the literature review chapter that the projected image of a brand was a possible approximation of brand trust (Keller, 2015). Figure 5 graphically displays the reactions of the sample to this factor.

It is illustrated that the total of 67.1% of the sample answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ when asked to evaluate the trustworthiness of Cadbury’s projected image. On the other hand, a large group of the respondents (28.7%) gave an indefinite response. It is suggested that despite the extensive social media presence of Cadbury, a significant part of the sample expressed doubts regarding brand trust. A possible implication of this outcome is that brand trust may be conceptualised depending on a wide variety of factors that do not necessarily relate to social media (e.g. the overall reputation of the company). Additional research is needed to verify the validity of this statement.

A similar distribution of the answers was observed in Question 8, which measured the degree of user engagement. This outcome is analysed graphically in the bar chart below.

The most important result elicited from Figure 6 is that 28.7% of the sample chose the response option ‘Neither’. While Cadbury often implemented the social media initiatives related to user engagement, not all customers were willing or able to participate. This means that the influence of Cadbury’s social media presence on brand trust could be limited by such mediating factor as subjective personal behaviours of the end consumers. However, it is acknowledged that since only the self-administered questionnaire survey was used to gather primary data in this dissertation, the researcher was unable to clarify the outlined issue further. Similar opinions were exhibited by the representatives of the research sample with respect to community identification. As shown in Appendix B, 32.8% of the surveyed customers of Cadbury were undecided in addition to the fact that the total of 23.2% of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with what was posited by Question 9 (see Appendix A). Furthermore, 60.1% of the study participants approved or strongly approved of the behaviours exhibited by other community members (Appendix B). Based on this discrepancy, it can be argued that the approval of conduct does not necessarily entail community identification in the social media setting. In addition, the outcomes further reinforced the idea that the influence of social media presence on brand trust is not direct, but rather affected by other attributes.

These findings are encapsulated in the next table comprised of the results of the statistical analysis for Cadbury’s projected image.

According to the established threshold of significance being lower or equal to 0.05, only ADV is considered a statistically significant variable (Rumsey, 2016). As the beta coefficient for ADV was positive, this meant that the more advertising messages were distributed through social media, the more trustworthy was the projected image of Cadbury. At the same time, other elements of the social media presence were unable to influence PRI. This suggests that firms aiming to increase their brand trust have to strategically implement the techniques influencing particular attributes of trust. A similar point can be made with respect to the outcomes for user engagement.

As shown above, the more user-generated content was leveraged by Cadbury, the more engaged its followers felt. This supports the overall assertion that social media presence can have a positive influence on brand trust. However, no statistically significant variables were discovered for community identification. This can be explained by the fact that the behaviours of the social media followers are not directly controlled by Cadbury, limiting the company’s ability to influence brand trust.

4.4. Discussion of the Findings

It is necessary to compare the results of this study with the existing body of knowledge on social media presence and brand trust. Starting with the core strategies of building and maintaining social media presence, Alalwan et al. (2017) highlighted the role of advertising on these platforms. This observation was supported in the current dissertation as the majority of the research sample reported that Cadbury distributed promotional messages through its social media channels. Nonetheless, the effects of these communications on brand trust remained limited to the projected image only. The key implication of this outcome is that firms have to rely on robust frameworks of social media presence combining messages of different types (e.g. advertising and user-generated content) in order to achieve a higher level of brand trust.

Another crucial technique of using social media with respect to branding was direct communications with the end consumers (Wang and Kim, 2017). As asserted by the participants of this study, Cadbury frequently engaged in dialogues with its followers on such websites as Facebook and Twitter. That said, this was not necessarily reflected in the measurements of brand trust employed by Cadbury. More specifically, direct communications was not among the statistically significant variables for the measurement of brand trust. Considering that engagement was one of the main measurements of brand trust, this outcome detailed a significant gap for Cadbury in terms of the company’s social media paradigm. Additional strategies would need to be implemented by the firm to boost the level of brand trust exhibited by its social media followers.

Turning now to user-generated content the significance of which was highlighted by Geurin and Burch (2016), the questionnaire respondents showed that Cadbury frequently encouraged the creation and distribution of this information along the company’s social media mix. The importance of this strategy was further illustrated by the outcomes of the statistical analysis. Nonetheless, the researcher was unable to clarify which exact types of the content were the most useful and productive. Moreover, the social media websites used by Cadbury were also considered as the core component of the firm’s presence (Rawat and Divekar, 2014). As it was emphasised by the research sample, Cadbury relied on a wide variety of platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Google+. While the impact of this strategy on the measurements of brand trust remains questionable, Cadbury could have benefitted from contacting a wider audience of social media users, thus amplifying the effects mentioned above.

Chapter 5: Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Summary of the Findings

The main aim of this study was to analyse the impact of Cadbury’s social media presence on brand trust among the online community members. It was proposed that brand trust was a component of the wider framework of brand equity and was influenced by projected image, community identification, the behaviour of other social media followers and the degree of user engagement (Keller, 2015). This addressed the first research objective. In terms of Cadbury’s social media presence, it was shown that Facebook, Twitter and Instagram were among the most popular platforms. Advertising messages, user-generated content and direct customer communications were the key instruments employed by Cadbury for building its brand on these websites. This research outcome pertained to the second research objective. However, only advertising messages and user-generated content had a noteworthy impact on the measurements of brand trust. This could be attributed to the shortcomings of Cadbury’s marketing function or the strong influence of the personal opinions and characteristics of the end consumers on brand trust. This discussion refers to the third research objective.

Overall, the major theoretical contribution of the study was that different measures of brand trust were affected by the diverse techniques of amplifying the social media presence of Cadbury. This implies that companies willing to improve the performance of their brand have to focus on the specifics aspects of trust. In terms of practice, this also adds pressure on Cadbury and similar organisations, as the dissertation revealed that a holistic approach to social media presence was necessary to influence the opinions and perceptions of the end consumers. Serious challenges may be involved since firms are unable to account for all measurements of trust (e.g. the behaviours of the community members).

5.2. Evaluation of the Findings

Since the hypotheses were established along with the theoretical framework, it is necessary to evaluate whether the dissertation has supported or rejected these theoretical assumptions. Hypothesis 1 was rejected by the study. Direct customer communications had no visible effect on the established measures of brand trust. At the same time, Hypothesis 2 was fully justified by the research project. Cadbury’s user-generated content positively influenced brand trust via consumer engagement. Speaking of Hypothesis 3, this theoretical proposition was dismissed by the study. Purely advertising messages had a notable impact on what was experienced by the study participants, especially with respect to the brand image of Cadbury.

5.3. Recommendations for Cadbury

In order to achieve the fourth and the final research objective, it is required to provide practical recommendations for Cadbury. One possible explanation of the results was that Cadbury’s efforts were insufficient to provide a consistent and positive influence on brand trust. Employee training might be a viable solution to this problem (Eby et al., 2017). Cadbury could focus on the innovative methods of using social media (e.g. satisfying the needs of the targeted customers) when designing and implementing such developmental programmes (Zhu and Chen, 2015). Nevertheless, this suggestion could entail significant financial and resource costs for Cadbury related to the overhaul of its organisational practices (Noe, 2016).

Another proposition to Cadbury would be to modify the elements of its social media presence. Specifically, the paradigm of content marketing may be adopted by the company (Ahmad et al., 2016). In other words, the firm can go beyond the elements of social media presence specified in this research project and distribute informative and useful messages regarding its activities (Ahmad et al., 2016). This should have a positive effect on branding (Ahmad et al., 2016). That said, it is believed that content marketing should be integrated with the remaining components of social media presence to be effective, which may pose a real challenge for Cadbury (Key and Czaplewski, 2017).

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

One of the main limitations of this study was that the project was mainly focused on the customer perspective of social media presence and brand trust. Interviews with the social media managers of Cadbury could provide a valuable insight of how the organisation has structured its social media presence and what factors have influenced its decision-making in terms of improving brand trust (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Finally, it can be stated that the study has only presented a snapshot overview of the current social media presence of Cadbury.

References

Aaker, D. (1992) “The value of brand equity”, Journal of Business Strategy, 13 (4), pp. 27-32.

Agnihotri, R., Trainor, K., Itani, O. and Rodriguez, M. (2017) “Examining the role of sales-based CRM technology and social media use on post-sale service behaviors in India”, Journal of Business Research, 81 (1), pp. 144-154.

Ahmad, N., Musa, R. and Harun, M. (2016) “The impact of social media content marketing (SMCM) towards brand health”, Procedia Economics and Finance, 37 (1), pp. 331-336.

Alalwan, A., Rana, N., Dwivedi, Y. and Algharabat, R. (2017) “Social Media in Marketing: A Review and Analysis of the Existing Literature”, Telematics and Informatics, 34 (7), pp. 1177-1190.

Balaji, M., Khong, K. and Chong, A. (2016) “Determinants of negative word-of-mouth communication using social networking sites”, Information & Management, 53 (4), pp. 528-540.

Brook, B. (2017) “Cadbury wins trademark battle against rival Nestlé over KitKat shape”, [online] Available at: http://www.news.com.au/finance/business/retail/cadbury-wins-trademark-battle-against-rival-nestl-over-kitkat-shape/news-story/1052ed0e42dd56ad9f4bd082ba7de286 [Accessed on 22 November 2017].

Bryman, A. (2016) Social Research Methods, 5th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2015) Business Research Methods, 5th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. (2014) Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, London: SAGE.

Darlington, R. and Hayes, A. (2017) Regression Analysis and Linear Models, New York: The Guilford Press.

Eby, L., Allen, T., Conley, K., Williamson, R., Henderson, T. and Mancini, V. (2017) “Mindfulness-based training interventions for employees: A qualitative review of the literature”, Human Resource Management Review, to be published.

Felix, R., Rauschnabel, P. and Hinsch, C. (2017) “Elements of strategic social media marketing: A holistic framework”, Journal of Business Research, 70 (1), pp. 118-126.

Finch, W., Bolin, J. and Kelley, K. (2016) Multilevel Modeling Using R, Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Focus on Pigments (2015) “Trademark colours: Cadbury vs Nestlé & Beiersdorf vs Unilever”, 2015 (9), pp. 6-7.

Foresman, G., Fosl, P. and Watson, J. (2016) The Critical Thinking Toolkit, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Geurin, A. and Burch, L. (2016) “User-generated branding via social media: An examination of six running brands”, Sport Management Review, 20 (3), pp. 273-284.

Giovanis, A. and Athanasopoulou, P. (2017) “Consumer-brand relationships and brand loyalty in technology-mediated services”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, to be published.

Given, L. (2015) 100 Questions (and Answers) About Qualitative Research, London: SAGE.

Goranko, V. (2016) Logic as a Tool, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Gray, D. (2016) Doing Research in the Business World, London: SAGE.

Harrigan, P., Soutar, G., Choudhury, M. and Lowe, M. (2015) “Modelling CRM in a social media age”, Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 23 (1), pp. 27-37.

Hyder, S. (2016) The Zen of Social Media Marketing, 4th ed., Dallas: BenBella Books.

Japutra, A. and Molinillo, S. (2017) “Responsible and active brand personality: On the relationships with brand experience and key relationship constructs”, Journal of Business Research, to be published.

Jung, A. (2017) “The influence of perceived ad relevance on social media advertising: An empirical examination of a mediating role of privacy concern”, Computers in Human Behavior, 70 (1), pp. 303-309.

Keller, K. (2015) Strategic Brand Management, 4th ed., Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Key, T. and Czaplewski, A. (2017) “Upstream social marketing strategy: An integrated marketing communications approach”, Business Horizons, 60 (3), pp. 325-333.

Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G. (2014) Principles of Marketing 15th Global Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Lee, J. and Hong, I. (2016) “Predicting positive user responses to social media advertising: The roles of emotional appeal, informativeness, and creativity”, International Journal of Information Management, 36 (3), pp. 360-373.

Lin, C., Wang, K., Chang, S. and Lin, J. (2017) “Investigating the development of brand loyalty in brand communities from a positive psychology perspective”, Journal of Business Research, to be published.

Link Humans (2017) “How Cadbury Uses Social Media [Case Study]”, [online] Available at: https://linkhumans.com/blog/cadbury [Accessed on 23 November 2017].

Lyon, A. (2016) Case Studies in Courageous Organizational Communication: Research and Practice for Effective Workplaces, New York: Peter Lang Publishers.

Martinez-Lopez, F., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R. and Esteban-Millat, I. (2017) “Consumer engagement in an online brand community”, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 23 (1), pp. 24-37.

McDaniel, C. and Gates, R. (2016) Marketing Research Essentials, 9th ed., Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Mondelez International (2016) “Form 10-K Annual Report 2016”, [online] Available at: http://ir.mondelezinternational.com/secfiling.cfm?filingID=1193125-16-469394&CIK=1103982 [Accessed on 22 November 2017].

Noe, R. (2016) Employee Training and Development, New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

O’Sullivan, E., Rassel, G., Berner, M. and Taliaferro, J. (2017) Research Methods for Pubic Administrators, 6th ed., New York: Routledge.

Osei-Frimpong, K. and McLean, G. (2017) “Examining online social brand engagement: A social presence theory perspective”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, to be published.

Ozuem, W. and Bowen, G. (2016) Competitive Social Media Marketing Strategies, Hershey: IGI Global.

Pernecky, T. (2016) Epistemology and Metaphysics for Qualitative Research, London: SAGE.

Phua, J., Jin, S. and Kim, J. (2017) “Gratifications of using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to follow brands: The moderating effect of social comparison, trust, tie strength, and network homophily on brand identification, brand engagement, brand commitment, and membership intention”, Telematics and Informatics, 34 (1), pp. 412-424.

Pruzan, P. (2016) Research Methodology: The Aims, Practices and Ethics of Science, Cham: Springer.

Rawat, S. and Divekar, R. (2014) “Developing a Social Media Presence Strategy for an E-commerce Business”, Procedia Economics and Finance, 11 (1), pp. 626-634.

Rubio, N., Villaseñor, N. and Yagüe, M. (2017) “Creation of consumer loyalty and trust in the retailer through store brands: The moderating effect of choice of store brand name”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34 (1), pp. 358-368.

Rumsey, D. (2016) Statistics for Dummies, 2nd ed., Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2015) Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed., Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Schutt, R. (2016) Understanding the Social World: Research Methods for the 21st Century, London: SAGE.

Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R. (2016) Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Shih, C. (2016) The Social Business Imperative, New York: Prentice Hall.

Teater, B., Devaney, J., Forrester, D., Scourfield, J. and Carpenter, J. (2017) Quantitative Research Methods for Social Work, London: Palgrave.

van den Hoonard, W. and van den Hoonard D. (2016) Essentials of Thinking Ethically in Qualitative Research, London: Routledge.

Wang, Z. and Kim, H. (2017) “Can Social Media Marketing Improve Customer Relationship Capabilities and Firm Performance? Dynamic Capability Perspective”, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 39 (1), pp. 15-26.

Zhu, Y. and Chen, H. (2015) “Social media and human need satisfaction: Implications for social media marketing”, Business Horizons, 58 (3), pp. 335-345.

Appendix