Written by Steve S.

Executive Summary

This dissertation examined the impact of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation stimuli on employee retention outcomes in British service companies. Quantitative data was collected from 100 service industry insiders through a questionnaire survey. The results were processed with the utilisation of graphical and statistical analysis to identify the effect of individual factors. It was discovered that salary and bonuses, fringe benefits, job security and management support were relevant for achieving the loyalty of current staff members. At the same time, such factors as career development opportunities, positive working environment and leadership style had a positive impact on the overall sense of motivation adequacy, which is in line with the findings of existing empirical studies and Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene theory.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

The problem of employee retention is highly critical in the modern business environment as organisations are becoming progressively more dependent on labour resources (Osabiya, 2015). As the training and development of organisational personnel usually require substantial investments, the loss of competent staff members significantly reduces overall productivity and profitability because these monetary resources do not generate positive outputs. At the same time, newly hired employees may fail to maintain high standards of servicing quality, which can further harm organisations (Natarajan and Palanissamy, 2015). While modern companies may implement some contractual measures to limit the possibility of such outcomes, proper motivation is still the primary instrument of achieving long-term employee retention (Harder et al., 2014). That said, the power of different motivational stimuli varies greatly depending on the context, industry and staff characteristics, which often reduces the effectiveness of organisational efforts if the information about these elements is inaccurate or unavailable (Al-Qeed et al., 2016).

1.2. Rationale for the Research

While extrinsic and intrinsic motivation stimuli have been studied by a number of management theories including the Motivation-Hygiene theory (Herzberg, 1959), the association between specific incentives and employee retention effectiveness may be different for various industries and contexts (Rafique et al., 2014). While some researchers established the positive correlation between tangible and intangible motivators and job satisfaction (Ismail and Ahmed, 2015; Osabiya, 2015), the findings of Biswakarma and Sharma (2015) and Janjhua et al. (2016) indicate that job satisfaction does not always lead to long-term loyalty. This substantiates the need to analyse the actual relevance of the extrinsic and intrinsic incentives available to contemporary organisations for achieving employee retention. This dissertation is focused on the UK context and the relatively understudied service organisations industry (Ghosh and Gurunathan, 2015) and seeks to reveal the role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators in achieving positive retention results.

1.3. Research Background

Almaaitah et al. (2017) discovered that employee retention was influenced by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors including career development opportunities and work-life balance. However, these researchers stated that a systematic approach associating different motivators with retention outcomes was not pursued by the majority of studies in this research field. Al-Qeed et al. (2016) positively evaluated the impact of intangible motivations on the reduction of intentions to leave among their respondents. Nevertheless, their evidence was limited to the public sector, while professionals from public organisations might demonstrate a lower degree of interest in monetary incentives in comparison with their private sector colleagues. Finally, the analysis of Thiriku and Were (2016) suggested that a uniform system of compensation and rewards could greatly benefit modern organisations by providing a balanced framework for achieving superior performance and loyalty. This study attempts to bridge these research gaps by exploring the role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation stimuli in employee retention.

1.4. Aim and Objectives

The aim of this dissertation is to explore the role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation stimuli in employee retention. This aim is achieved through the following research objectives:

- To analyse what extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli are available to contemporary organisations.

- To explore the motivational power of these incentives in terms of increasing the loyalty of staff members towards the employer.

- To evaluate the impact of these stimuli on the retention and satisfaction of employees in UK service organisations.

- To formulate practical recommendations on how to improve staff loyalty outcomes through the use of motivational incentives.

1.5. Relevance and Potential Contribution

This study provides empirical evidence about the most effective motivational instruments that can be used by all companies to achieve good employee retention outcomes. At the same time, the produced findings extend the theoretical understanding of motivation stimuli in general and contribute to the body of existing human resource management (HRM) literature.

1.6. Expected Findings and Limitations

This study attempts to identify specific extrinsic and intrinsic factors that have a statistically significant impact on employee retention. It also reveals the perceived relevance of individual factors, which allow service industry employers to balance their approach to staff motivation and retention and utilise organisational resources with greater efficiency. However, this study is limited to one country, which can make its findings non-generalisable to other contexts. Additionally, it is exclusively focused on the service industry.

1.7. Dissertation Structure

The Literature Review chapter analyses existing empirical studies to build the theoretical foundation for further analysis. The Methodology section evaluates available research instruments and substantiates the choice of the most appropriate philosophies, approaches and strategies. The Analysis of Findings chapter processes the collected primary data with the use of applicable analysis tools to identify existing correlations and patterns relevant for answering the research questions. The Discussion and Conclusion section summarises the findings and provides practical recommendations on improving the effectiveness of employee retention activities in service organisations.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Stimuli

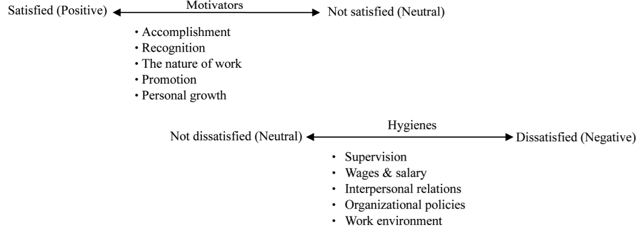

The choice of effective extrinsic and intrinsic motivational instruments is highly relevant for achieving high levels of employee motivation (Rafique et al., 2014). That said, the association of the resulting job satisfaction with other outcomes such as actual productivity or employee retention is relatively understudied and may differ in various industries and organisations. One of the theories linking motivation and job satisfaction with intrinsic and extrinsic motivators is Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene theory (Herzberg, 1959). This framework assumes that tangible incentives such as monetary remuneration have limited power as they are non-unique in the contemporary environment and do not necessarily bring long-term gratification to employees. On the other hand, such incentives as development perspectives, the capability to grow and develop as a professional and other job enrichment options are critical for employee retention and for maintaining high levels of motivation (Nakhate, 2016).

Figure 1: Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene Theory

Source: Hui-Chin and Yang (2015, p. 56)

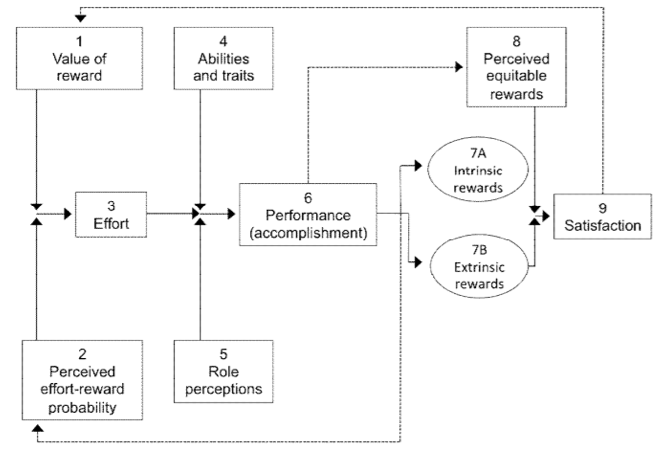

An important element of employee motivation is the degree of coherence between employee expectations and reality that is analysed by the expectancy theory (Lee and Raschke, 2016). Staff members expect that their efforts result in greater performance that are noted and rewarded by their executives. However, this mechanism may not function properly in some companies, which can lead to growing dissatisfaction and employee turnover (Haider et al., 2015). Therefore, organisations have to understand the expectations of their employees, communicate their performance goals and reward the successful efforts leading to superior performance. Similar views were expressed by Porter and Lawler (1968) who expanded the existing expectancy concepts by introducing such parameters as the perceived significance of the reward, the skills and traits possessed by employees and perceived equitability. Hence, the level of motivation largely depends on the actual and perceived capability of employees to achieve their goals within the organisation as well as the perceived fairness of rewards distribution, which, in turn, can decrease the relevance of some incentives due to personal views or the sense of unfair treatment.

Figure 2: The Model of Expectation by Porter and Lawler

Source: Porter and Lawler (1968, p. 165)

Extrinsic motivators may include salaries, fringe benefits and other tangible bonuses (Wei and Yazdanifard, 2014). In turn, intrinsic rewards are more intangible and may involve encouragement, development and support, empowerment and other positive reinforcements. While these motivators usually do not require substantial resources, and may be more attractive to the employer, they cannot be utilised exclusively without their extrinsic counterparts and are generally viewed as the ‘extra’ benefit added to the primary offering. Safiullah (2014) added job security and promotion opportunities to the tangible rewards suggested by Wei and Yazdanifard (2014). At the same time, intrinsic rewards are associated with psychological incentives such as the availability of challenges, positive working environment and employer attitude, the opportunity to switch between different positions and the overall sense of achievement and doing something important for both the employee and the society in general.

According to Acar (2014), the impact of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators does not depend on the age of employees. This researcher discovered that the relevance of these two factor groups was similar for both Generation X and Generation Y employees. Significant extrinsic factors included job security, comfortable working environment, fringe benefits, considerate supervision, adequate earnings and restricted working hours. At the same time, the group of relevant intrinsic motivators included the recognition of individual achievements, interesting goals, responsibility, respect and participation in the decision-making process (Acar, 2014). These findings are partly in keeping with Kossivi et al. (2016) who also discovered that such intangible factors as management support and corporate leadership style were highly relevant for stimulating employees. While they were not directly associated with employee personal benefits, they influenced the working environment and the degree of its supportiveness, which resulted in intrinsic motivation in the form of self-confidence, the sense of recognition and relationships quality (Kossivi et al., 2016).

2.2. Employee Retention

Employee motivation is directly associated with the intention to quit or the loyalty towards the company (Ghosh and Gurunathan, 2015). As modern organisations depend on the quality of their workforce, the retention of competent and talented staff members becomes their strategic goal. As noted by Chowdhury et al. (2017), the loss of professional and highly skilled workers leads to negative short-term and long-term effects. Additionally, the lack of commitment decreases the morale of employees as well as their intentions to contribute fully to the development of the companies they do not seek to stay in for the next several years. Staff retention is highly critical for contemporary organisations due to a number of reasons. Firstly, the loss of trained and competent specialists may lead to a decreased quality of customer service (Azeez, 2017). Secondly, some workers can follow the leaving staff members if they are loyal to them rather than the enterprise they work for. Thirdly, the costs of training new employees to replace their predecessors may exceed the cost of motivating existing personnel members to stay (Mishra and Mishra, 2017).

At the same time, employee turnover results in both direct and indirect costs (Chowdhury et al., 2017). The former category includes the expenses associated with the recruitment and training new specialists, hiring temporary staff members and spending the time of managers. In turn, the latter category is more discrete and includes costs such as the decrease in servicing quality, the concerns of other employees about their job security and the loss of positive organisational atmosphere due to higher work-related stress. However, the retention of high-profile workers may be complicated because many specialists frequently move between different companies (Kassa, 2015). Hence, it may be difficult to offer some unique benefits that can increase the attractiveness of the current employer, which substantiates the relevance of selecting the most effective intrinsic and extrinsic motivators.

Turnover can also be linked with individual reasons and organisation-level reasons (Chowdhury et al., 2017). In the first situation, employee decisions to leave can be dictated by their age, personal situations or interpersonal relationships with their colleagues. In turn, organisation-level motivational factors impact all staff members to a certain degree and may lead to substantial organisational underperformance as well as the inability to reach strategic goals (Chowshury et al., 2017). The findings of Rono and Kiptum (2017) also suggest that the losses associated with employee turnover can vary in different companies and industries. While retail sales stores can tolerate low retention rates, educational institutions and service industry companies may suffer from the decreased trust of their clients who may stop using their services or follow the leaving staff member to his or her new place of employment. Similar to motivation, employee retention is moderated by a large number of factors including demographic characteristics, personal preferences and industry-related differences (Adeoye et al., 2016). Therefore, the relevance of individual motivators may vary in each particular case, meaning employers must be aware of the most relevant incentives in their sphere of operation and adjust their organisational policies accordingly to maximise performance and retention results.

While individual incentives may vary in their impact on employee retention, the findings of Okech (2015) indicated that effective loyalty development required the combination of multiple extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Specifically, staff members needed to get good compensation and also see the opportunities to develop within the organisation in terms of their career advancement and professional growth (Okech, 2015). That said, these intrinsic opportunities may not be available within small and medium enterprises (SMEs) since they may lack the resources available to their larger counterparts. It can be summarised that employee retention is one of the key issues in service organisations, which involve a large share of interpersonal communication and highly skilled employees who are governed by expectations of proper rewards for their achievements (Sutha and Chitra, 2016). Specifically, they expect higher flexibility, monetary compensation and the sense of a shared culture. The last factor is similar to positive working environment and suggests that all workers support each other, cooperate to solve the problems of customers and their achievements are properly rewarded and recognised by the organisation.

2.3. The Impact of Motivation Stimuli on Employee Retention

The study of Nemeckova (2017) indicated that employee retention in the examined companies depended on both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Crisis periods were generally associated with the greater relevance of tangible motivators such as healthcare schemes, higher salaries, job stability and life insurance options. However, some intangible benefits including training and development, educational programmes and up-skilling are equally relevant (Shmailan, 2016). At the same time, these options were highly demanded due to the perceived easiness of finding a new job in the case of the loss of employment, which raises the question of the relevance of these incentives for employee retention (Nemeckova, 2017). Employee motivation can also be viewed as a long-term factor since some motivators can ensure only short-term loyalty and job satisfaction (Haider et al., 2015). While monetary incentives and bonuses can improve employee attitudes towards the company at a particular moment, long-term retention is usually achieved by offering development options, future career opportunities and challenging goals that lead to personal development and increase the degree of self-confidence and satisfaction (Almaaitah et al., 2017). However, professional growth can also lead to the decision to leave the organisation and seek better employment variants (Biswakarma and Sharma, 2015).

The study of Ismail and Ahmed (2015) revealed that the participants were primarily motivated by such factors as organisational respect and trust, the opportunities for education and personal development, the honesty of internal communication, the quality of teamwork, the work-life balance and the fairness of the decisions related to promotions and reward distribution. At the same time, these findings may be context-specific as the analysed employees were working in Malaysian and UAE organisations. However, Muslim et al. (2016) confirmed the positive impact of factors such as working environment, salary and job characteristics on employee retention in the analysed Malaysian organisation. These researchers additionally emphasised the role of managerial competence and awareness in achieving this outcome and maintaining good motivation levels in the studied company. Specifically, professional managers could understand the reasons of employee dissatisfaction and adjust work tasks and motivational incentives to individual personnel members and teams to maximise profitability and productivity (Muslim et al., 2016).

Mishra and Mishra (2017) discovered that the impact of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators can be different depending on employee age segments. Being more precise, Generation Y workers were highly motivated by intrinsic factors as they viewed the extrinsic ones as ‘granted’ and did not view them as relevant. While this situation may change during crisis periods, the researchers came to the conclusion that this pattern should be taken into account by contemporary organisations as younger staff members are beginning to replace Generation X personnel members (Mishra and Mishra, 2017). That said, the sample size of this study was limited to 50 respondents, which could negatively impact the generalisability of the findings. Almaaitah et al. (2017) arrived at the conclusion that employee commitment and retention were positively influenced by career development opportunities, work-life balance and compensations availability. However, these researchers also noted that the evidence from this sphere was limited and previous studies had been exploring individual extrinsic and intrinsic factors in isolation (Almaaitah et al., 2017). The suggested alternative to this approach was the incorporation of individual incentives into a system of variables influencing retention, which is performed in this dissertation.

The study of Eberendu and Kenneth-Okere (2015) revealed that the recognition or achievements and good work, performance-based rewards and the encouragement of fulfilling projects were the most relevant factors for employee retention in the analysed organisations. These researchers also discovered that these incentives had a similar impact on both regular staff members and managers, which suggests their universal character (Eberendu and Kenneth-Okere, 2015). However, this study was performed in the healthcare industry and its results may have limited generalisability to other contexts. Al-Qeed et al. (2016) also established a positive correlation between the recognition of employee achievements and employee achievements and retention. That said, this research project was focused on public sector organisations that are traditionally more sensitive towards intrinsic motivation factors such as the positive organisational climate and the encouragement of creativity and productivity through non-monetary rewards (Rafique et al., 2014).

The analysis performed by Thiriku and Were (2016) discovered that the development of a uniform system of rewarding outstanding employee performance through a combination of monetary and non-monetary rewards was highly significant for achieving good retention outcomes. At the same time, employees were also motivated by well-designed work-life balance schemes, regular performance evaluations and discussions, engaging corporate culture and positive managerial communication (Thiriku and Were, 2016). By contrast, the findings of Shmailan (2016) indicated that employee loyalty was also associated with the feeling of belonging to their organisation. The staff members who link their individual success and work goals with the positive results achieved by their company were found by Shmailan (2016) to demonstrate greater retention and motivation than their colleagues who felt separated from their employer. These unengaged specialists also provide inferior customer service, which is dangerous for the sustainability of business operations. In the same vein, Harder et al. (2014) established the significance of the work-life balance and the sense of contributing to the well-being of others. However, these factors were collected from a single public sector organisation, which could negatively impact their applicability to profit-oriented companies.

Janjhua et al. (2016) discovered that the main retention antecedents were the sense of fairness in terms of compensation and recognition, the availability of fringe benefits, a cooperative working environment and training and development opportunities provided by contemporary organisations. At the same time, the impact of these factors was similar for both male and female respondents, which supports the suggestions of Eberendu and Kenneth-Okere (2015) about the universal nature of motivational incentives. Biswakarma and Sharma (2015) identified that compensation, working environment quality, career development opportunities and training and development decreased turnover intentions in the hotel industry. However, the availability of challenging goals was insignificant within the scope of employee loyalty, which suggests that different areas of employment may demonstrate various motivational patterns. It is also possible that the findings of this study are industry-specific and may not be generalisable to other contexts.

The analysis of the telecom sector by Haider et al. (2015) established that training and development opportunities were significant for achieving commitment and superior performance. The possession of high-level skills directly influenced the overall productivity and, therefore, employee performance and monetary results. Additionally, the respondents criticised their employers for the lack of attention towards this highly relevant factor, which suggests that it is widely underutilised in the modern business environment. Finally, Wakabi (2016) identified that the leadership style implemented in organisations influenced the intentions to leave. The researcher concluded that the compatibility of management styles with employee expectations was critical for avoiding cultural clashes. Additionally, the awareness of the feelings and perceptions of staff members was a necessary protective measure for reducing employee turnover rates and preventing conflicts (Wakabi, 2016). Hence, it can be suggested that the congruence between employee perceptions and actual leadership practices may result in higher degrees of satisfaction and retention. However, the majority of the analysed empirical studies were not focused on the service industry, which substantiates the need to close this gap through the completion of this dissertation.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1. Introduction

The proper choice of methodological instruments is critical for maintaining the effectiveness and accuracy of data collection and processing (Saunders et al., 2015). It also determines the reliability, validity and generalisability of dissertation findings. This chapter evaluates available philosophies, strategies and approaches and substantiates the selection of specific methodological instruments necessary to address the main research aim and objectives.

3.2. Research Philosophy

Academic studies usually rely on one of the three primary research philosophies, namely axiology, ontology and epistemology (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Axiology is concerned with establishing the role of values in the research process (Creamer, 2017). It accepts the existence of personal views of both the researcher and the participants that can influence the research process, which makes it susceptible to bias. In turn, ontology views reality as socially constructed and studies different perceptions of reality to gain an in-depth understanding of complex social phenomena (Klenke, 2016). Finally, epistemology explores the process of knowledge generation and seeks to exclude the researcher from this process (Rovai et al., 2013). This dissertation adheres to the ‘natural scientist’ approach that views reality and its elements as measurable and existing independently from all members of the research project. Therefore, epistemology is selected as the most applicable philosophy that promotes the objective approach to data collection and processing.

Different views of reality are also reflected in the positivist and interpretivist paradigms (Johannesson and Perjons, 2014). Positivist researchers seek to approach reality from the objective standpoint as a measurable object that exists separately from all persons involved in the research process (Saunders et al., 2015). Hence, positivist studies are highly compatible with the quantitative approach to data collection and produce generalisable and reliable results. On the contrary, interpretivism is highly effective in exploring the views of several unique respondents who possess in-depth knowledge that cannot be collected from the general population (Fox et al., 2014). This paradigm has lower generalisability as the data may contain individual bias. This dissertation seeks to explore the motivation stimuli influencing all employees in UK service organisations and does not seek to collect any unique knowledge from individual respondents, which is not available elsewhere. Hence, the positivist approach is the most applicable one for addressing the objectives set by this project.

3.3. Research Approach

Deductive studies begin with the analysis of existing theories that are utilised to develop the conceptual framework of a dissertation (Dainton and Zelley, 2014). Afterwards, this model is tested against new contexts to confirm or discard the earlier formulated research hypotheses. While this approach generates highly reliable and generalisable findings, it does not involve the generation of new theories (Saunders et al., 2015). Hence, it may not be suitable for studying new areas of research where no established theories are available. On the contrary, inductive studies progress from data analysis to formulating genuine hypotheses on the basis of unique and unusual correlations found in the collected data (Fortune et al., 2013). This approach also supports non-linear direction of the research but is generally more time-consuming and less predictable. Employee motivation and retention is a well-studied research area and there are multiple established theories that define these concepts, which suggest the choice of the deductive method for this dissertation.

3.4. Research Strategy

Research studies can utilise qualitative and quantitative strategies (Johnson and Christensen, 2013). The first approach is highly compliant with interpretivism and supports the collection of data from a small sample of unique respondents with the use of such instruments as unstructured in-depth interviews. At the same time, qualitative studies have limited generalisability and do not support the use of statistical instruments. In turn, quantitative studies usually involve large samples of the respondents that provide highly structured data (Grove et al., 2014). This approach facilitates the application of statistical analyses for information processing and improves the overall reliability and generalisability. This dissertation seeks to collect homogenous structured data from a large sample of the respondents, which suggests the use of the quantitative strategy.

3.5. Data Collection Method and Sampling

The sample size is highly significant for ensuring good reliability in quantitative studies and applying statistical instruments to process the collected data (Ahn et al., 2014). This project involved 100 respondents, which is expected to be sufficient for generating reliable and generalisable findings. The need to collect structured and homogenous data suggested the use of the questionnaire survey method (Bryman and Bell, 2015). This instrument is less obtrusive for the participants than qualitative interviews. Questionnaires are also more convenient for the researcher and the respondents who can complete the administered forms at any moment. The lists of questions were distributed through multiple online resources and the email addresses published on corporate resources. The need to compensate for the low response rates in social studies suggested the administration of approximately 300 questionnaires to obtain the required sample size (Fowler, 2013). The sampling method selected for this dissertation can be characterised as convenience non-probability sampling. This instrument is generally more convenient for both the researcher and the participants and improves the response rates (Boswell and Cannon, 2014). Likert scales were utilised to facilitate the completion of survey forms.

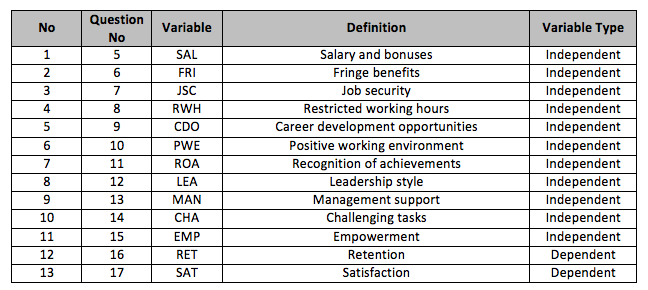

The following table presents the list of variables formed on the basis of the Literature Review section and coded into the questionnaire forms.

Table 1: Variable Definition Chart

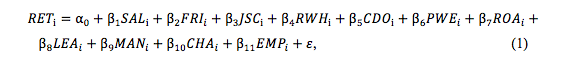

The regression model for the ‘RET’ variable has the form of the following equation:

where, ‘RET’ is the intention to stay in the current company for the next 3-5 years (a dependent variable), α0 is a constant, β1, 2, 3…11 are indicators that influence the independent variables, namely ‘SAL’, ‘FRI’, ‘JSC’, ‘RWH’, ‘CDO’, ‘PWE’, ‘ROA’, ‘LEA’, ‘MAN’, ‘CHA’ and ‘EMP’ (i=1, 2, 3…100) and ε is residuals.

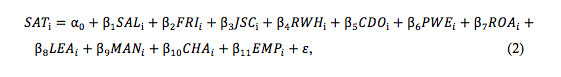

The regression model for the ‘SAT’ variable has the form of the following equation:

where, ‘SAT’ is the degree of satisfaction with the incentives offered by the company (a dependent variable), α0 is a constant, β1, 2, 3…11 are indicators that influence the independent variables, namely ‘SAL’, ‘FRI’, ‘JSC’, ‘RWH’, ‘CDO’, ‘PWE’, ‘ROA’, ‘LEA’, ‘MAN’, ‘CHA’ and ‘EMP’ (i=1, 2, 3…100) and ε is residuals.

A set of testable hypotheses is presented as follows:

H0: There is no statistically significant link between extrinsic and intrinsic motivators and employee retention.

H1: Extrinsic stimuli produce a strong positive impact on employee retention.

H2: Intrinsic stimuli produce a strong positive effect on employee retention.

3.6. Analysis Process

The administered questionnaires were divided into four primary sections, namely the respondent background, extrinsic motivators, intrinsic motivators and loyalty towards the company. The participants were required to provide the information about their age, position, company size and employment duration. The second and third sections were focused on the relevance of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators identified in the Literature Review section. Finally, the last section evaluated the degree of loyalty towards the company and the general perceptions related to the utilisation of motivational instruments by the management. The collected data was processed with the application of graphical analysis and statistical analysis tools (Anderson et al., 2014). The first instrument allowed the researcher to identify the correlations between individual variables and discuss the relevance of different motivational factors (Ribeiro, 2017). The second instrument in the form of linear regression revealed the impact of these incentives on the degree of current loyalty and the overall satisfaction with company efforts in this sphere. The SPSS and Excel software was utilised to process the collected data and perform the statistical and graphical analysis.

3.7. Ethical Issues

All contemporary studies must take into account applicable ethical considerations and regulations (Wiles, 2012). Specifically, the participants must be able to maintain their anonymity and have the right to cancel their participation at any moment for any reason. The collected data did not contain any personal information and was stored on a password-protected device. It was not disclosed to any third parties for any purposes and all analyses were performed by the researcher.

Chapter 4: Analysis of Findings

4.1. Respondent Background

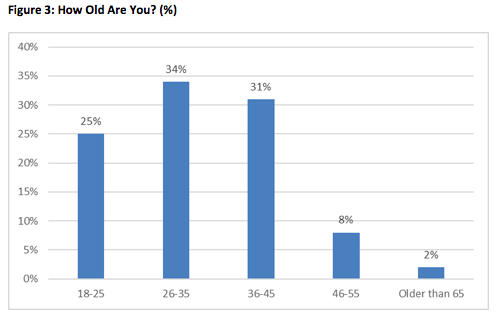

The division of the respondents into age groups is presented as follows.

The majority of the respondents belonged to the 18-45 years old group with only 10% of them being older than 46 years old. This may suggest a greater preference for intrinsic motivators within the scope of the findings of Mishra and Mishra (2017) due to the younger age of the respondents.

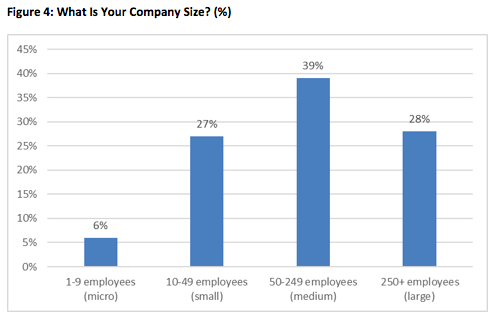

A total of 67% of the respondents were employed by service organisations with 50 and more employees while 39% of the participants were working for companies hiring 50-249 employees. These findings reflect the situation in medium and large UK companies while small and micro enterprises do not receive equal representation. This may impact the results due to the fact that larger organisations usually have larger resources and can offer a greater range of motivators in comparison with their smaller counterparts (Wynarczyk et al., 2016). They also demonstrate a greater interest towards extrinsic incentives because they view these instruments as generally more powerful and easier to utilise.

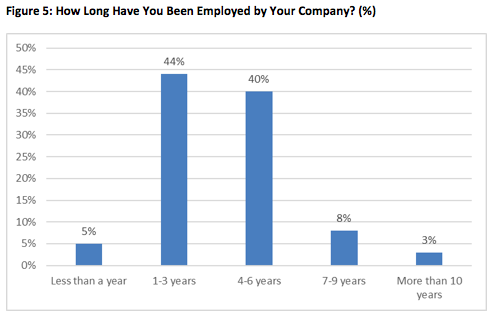

A total of 88% of all respondents were employed for 1-6 years. While this can impact retention incentives in the case of some employees according to Gunawan and Amalia (2015), this is an individual-level factor that does not necessarily affect the overall intention to stay in a company. That said, the staff members with a limited term of employment may not be able to evaluate the long-term perspective of motivational practices utilised by their organisations.

4.2. Extrinsic Motivators

The extent to which the respondents are provided with the previously discussed extrinsic motivation stimuli is analysed in this section.

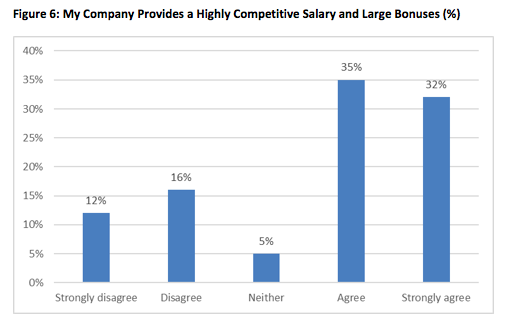

Competitive salary and bonuses availability were relevant to the aggregate of 67% of the participants while a total of 28% of them did not view this incentive as critical. These results are in line with the findings of Nemeckova (2017) and Nnaji-Ihedinmah and Egbunike (2015). However, the lack of interest towards this factor in the case of some employees may indicate that it is viewed as a hygiene factor rather than a motivator.

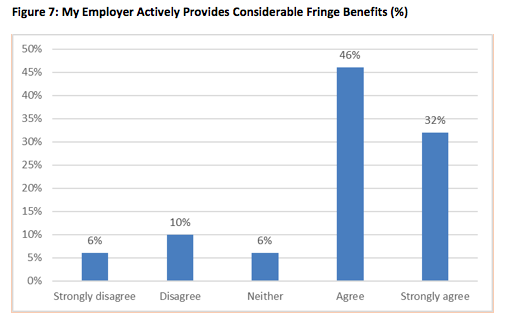

In total, the relevance of fringe benefits was recognised by 78% of all respondents, which may indicate that the unstable post-Brexit situation increases the relevance of this extrinsic motivator as a source of greater stability (Hestermeyer and Ortino, 2016). These results also confirm the suggestions of Janjhua et al. (2016) concerning the importance of tangible incentives for employee motivation.

The job security factor obtained controversial evaluations with the aggregate of 54% of the respondents viewing it as a relevant one and a total of 41% of the participants disagreeing and strongly disagreeing with its relevance. This may be explained by the fact that the financial crisis and the post-Brexit political and economic instability in the UK negatively influence the perceptions of staff members concerning the stability of their company (Lehmann and Zetzsche, 2016). Hence, the perceived job security in all organisations including service firms may be compromised as employers cannot get reliable guarantees in terms of the future job security situation.

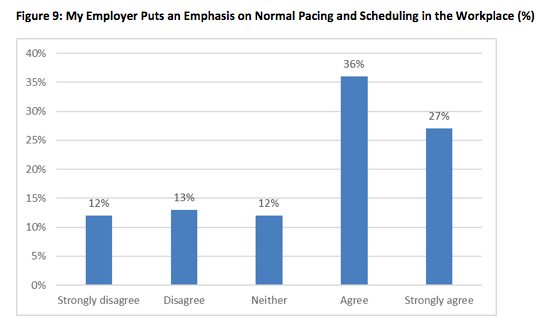

Restricted working hours were positively appraised by the aggregate of 63% of the respondents, which indicates that the work-life balance is relevant for UK employees working in service organisations. These findings are in line with the results obtained by Acar (2014) and Morrow et al. (2014) and suggest that the benefits of scheduling such as lower stress levels and a better work-life balance may have a positive impact on employee motivation and retention.

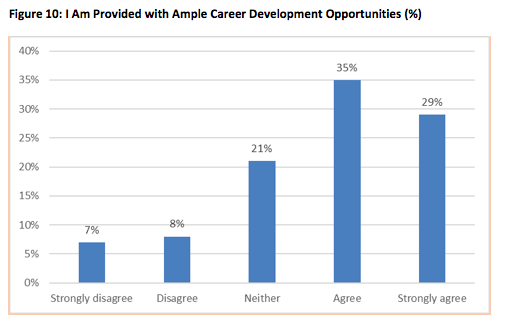

Finally, a total of 64% of the respondents were motivated by the availability of career development options. This confirms the findings of Almaaitah et al. (2017) and Anthony and Weide (2015) concerning the relevance of this factor for retaining employees in a long-term perspective. However, the results obtained by Haider et al. (2015) also suggest that this motivator must be complemented by other incentives to prevent proactive and professionally developing staff members from seeking more beneficial employment options.

4.3. Intrinsic Motivators

In this section, the reader is provided with the participants’ evaluations and perceptions of a range of the previously identified intrinsic motivators.

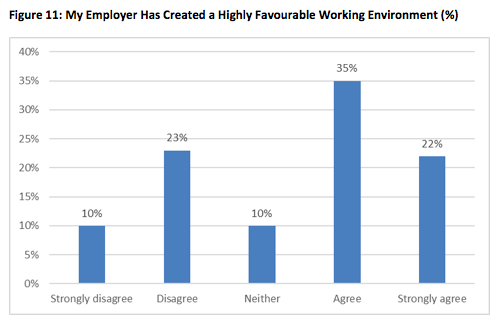

Positive working environment was critical for the aggregate of 56% of the respondents. That said, 33% of them disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement suggesting its relevance, which may indicate that service organisations are individual-centred rather than team-oriented (Gunawan and Amalia, 2015). However, this result can also be explained by the high individualism of the UK culture within the scope of the Hofstede Cultural Dimensions framework (Hofstede-Insights, 2017).

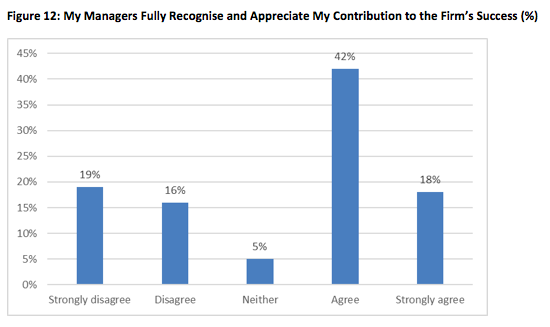

The recognition of achievements was positively appraised by a total of 70% of all respondents. These results suggest that this factor is highly relevant for motivating service industry professionals, which is in line with the findings of Eberendu and Kenneth-Okere (2015) and Muchiri et al. (2016). This also confirms the earlier identified individualism of employees from this sector and the UK in general (Gunawan and Amalia, 2015; Hofstede-Insights, 2017).

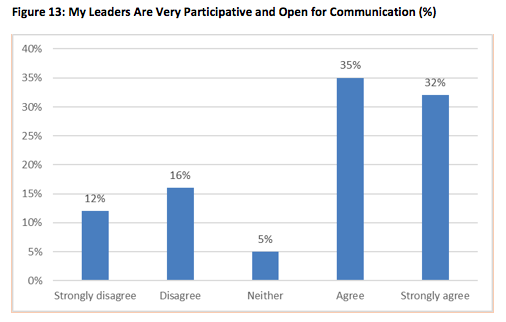

The aggregate of 67% of the participants reported that their leaders were open for communication and participation. This confirms the suggestions of Wakabi (2016) that the proper choice of the leadership style is highly relevant for employee motivation and retention. However, the fact that a total of 28% of the respondents did not view this factor as relevant may indicate the need to combine this incentive with other stimuli to get better results from all individual staff members.

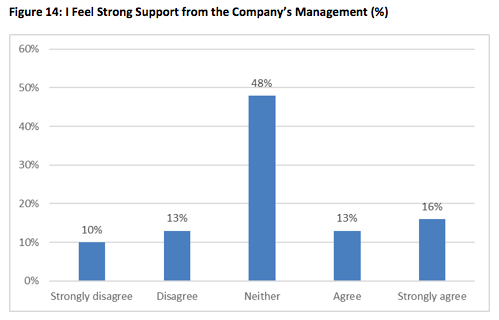

As much as 48% of the respondents could not confidently report that they felt any support from the management of their company. This may indicate the existence of a substantial problem in terms of intrinsic motivators in UK service organisations. This is highly concerning within the scope of the findings of Wei and Yazdanifard (2014) because managerial support influences both the processual job satisfaction and the overall efficiency of newly employed staff members. Hence, the underutilisation of this practice may lead to the lack of effectiveness and the sense of underperformance on part of both employees and their superiors (Kossivi et al., 2016), which may lead to the loss of loyalty and the decision to move to another company or industry.

A similar problem existed within the scope of challenging tasks availability with 22% of the respondents being uncertain about the existence of this incentive in their organisation. While a total of 54% of the participants recognised this factor as a relevant one, the relatively high percentage of neutral responses suggests that this motivator is not properly presented to all staff members. This is highly troublesome within the scope of the findings of Safiullah (2014) because the absence of this element negatively influences self-confidence and the sense of achievement associated with a particular employment position.

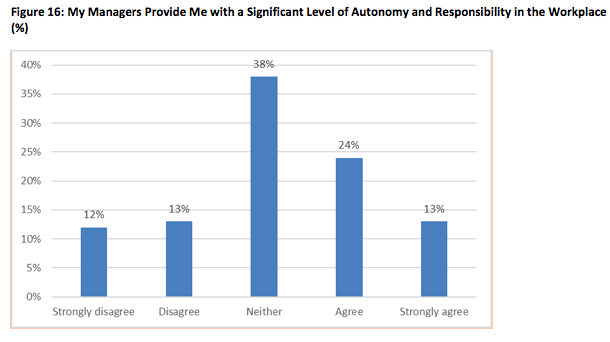

Similarly, autonomy and responsibility were not recognised by 38% of the participating specialists. This discards the suggestions of Wei and Yazdanifard (2014) in relation to the relevance of this factor for achieving good motivation and retention results. That said, the lack of these incentives as well as the earlier identified absence of challenging goals may also decrease personal development and professional growth aspirations (Haider et al., 2015).

4.4. Loyalty towards the Company

The extent to which the respondents are loyal to their company is presented as follows.

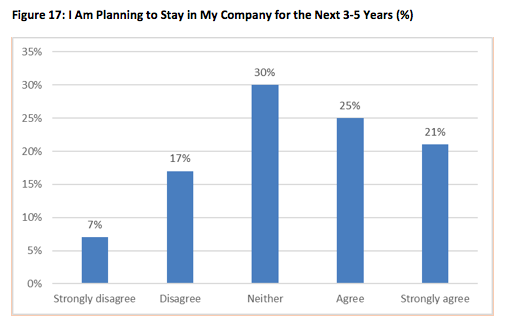

While in total, 46% of the respondents were planning to stay in their current organisation, as much as 30% of them were uncertain about this decision. This may suggest that the situation in the UK services industry is affected by the global financial crisis and post-Brexit market uncertainty, which reduce the degree of confidence in relation to the stability of existing employment opportunities (Mitsakis, 2014). At the same time, the high degree of uncertainty may also indicate that the studied organisations substantially underutilise their motivational instruments, which creates an opportunity to improve these outcomes through better employee retention policies (Thiriku and Were, 2016). These results may also be caused by a greater shift towards extrinsic incentives identified in the previous section.

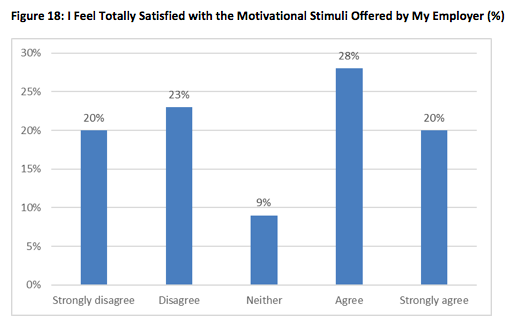

The number of employees dissatisfied and satisfied with the motivational stimuli offered by their organisation was approximately the same. This suggests that the effectiveness of utilising extrinsic and intrinsic incentives in the researched companies is sub-optimal, which may be caused by the lack of resources or the inefficient choice of motivational strategies (Osabiya, 2015). The earlier identified preference for tangible incentives on part of the studied organisations is controversial to the suggestions of Al-Qeed et al. (2016) who discovered that the excessive use of these motivators without balancing them with intangible ones might result in decreased retention and job satisfaction.

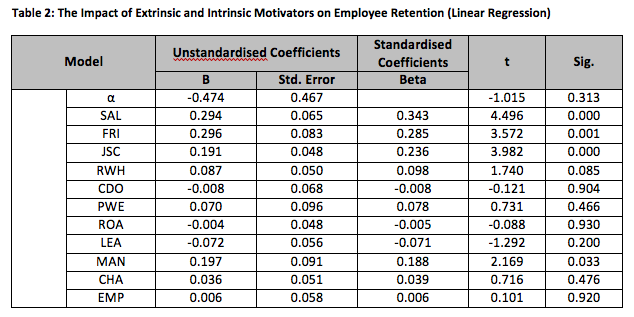

The linear regression analysis of employee retention predecessors demonstrated that salary and bonuses, fringe benefits, job security and management support had a statistically significant impact on the loyalty or staff members and their intention to stay in their company for the next 3-5 years. The beta values were positive in all cases, meaning the correlation between the variables is positive. The results confirmed the suggestions of Muslim et al. (2016), Safiullah (2014) and Wei and Yazanifard (2014). However, they also demonstrated that service industry employees did not view intrinsic incentives as equally powerful because only a single factor was relevant for loyalty development.

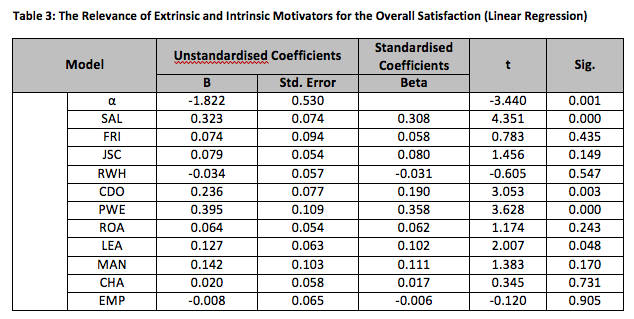

The linear regression analysis of overall satisfaction predecessors demonstrated that salary, career development opportunities, positive working environment and leadership style had a statistically significant impact on the perceived adequacy of motivation in the studied organisations. This statement is made since the Sig. of the mentioned predictors is lower than the threshold value of 0.05. The beta values were positive in all cases, indicating the correlation between the variables is positive. This is in line with the suggestions of Muslim et al. (2016), Okech (2015) and Wakabi (2016). However, the perceived relevance of extrinsic and intrinsic factors was more balanced in comparison with the previous regression results.

4.5. Discussion

The majority of the respondents represented medium and large service organisations in the UK, which could influence the availability of specific resources and motivational incentives. The significance of salary, job security and fringe benefits recognised by a large share of the respondents is in line with the findings of Muslim et al. (2016) who reported the high relevance of extrinsic motivators in modern organisations. These results also confirm the suggestion that extrinsic motivators can be viewed as both hygiene factors and motivators and are highly relevant for ensuring good employee performance and retention (Ismail and Ahmed, 2015; Osabiya, 2015). Similarly, working process organisation factors such as career development opportunities and scheduling in the workplace had a substantial significance for a large share of the participants. Hence, it can be concluded that the analysed extrinsic incentives had a strong impact on the overall motivation levels in the analysed context.

On the contrary, intrinsic motivators had limited power according to the respondents as the number of non-motivated employees varied between 23 to 35% depending on the specific factor. This result is controversial to the suggestions of Almaaitah et al. (2017) and Al-Qeed et al. (2016) who viewed these types of incentives as powerful motivators that were as effective as extrinsic ones. The fact that favourable working conditions and the recognition of individual contribution had limited importance for the respondents can be explained by the high individualism of the UK culture in general (Hofstede-Insights, 2017) and the service industry in particular (Sutha and Chitra, 2016). In this context, employees are working with clients directly and may not view team-level factors as relevant for them. At the same time, as much as 48% of the respondents did not receive any support from their managers. This is a troublesome indicator because new employees in these companies may be unable to succeed without external assistance and may choose to leave the organisation due to the absence of tangible results.

Similar response patterns in terms of challenging tasks availability and the degree of autonomy and responsibility in the workplace suggest that the analysed companies underutilise these intrinsic incentives or do not provide them to all staff members. This can decrease the overall sense of achievement according to Safiullah (2014) and may be viewed as a negative sign. The problem is especially evident in the case of employee empowerment as 38% of all respondents did not report any experience in relation to this indicator. The identified relevance of such extrinsic motivators as fringe benefits, job security, salary and bonuses within the scope of the statistical analysis indicates that UK employees are primarily motivated by financial incentives. This may be explained by the impact of the current financial and political instability that forces people to adhere to hygiene factors rather than less tangible motivators (Hestermeyer and Ortino, 2016).

At the same time, only managerial support had a statistically significant impact on employee intentions to stay, which suggests that intrinsic motivators are less powerful in this aspect within the scope of the service industry. Similarly, only two intangible incentives, namely positive working conditions and leadership style were relevant for creating the sense of being properly rewarded, while the salary factor was positively appraised in both cases. That said, career development opportunities also influenced the satisfaction of the respondents, which confirms the findings of Almaaitah et al. (2017). This suggests that intrinsic motivators can be useful for extending the hygiene incentives and contributing to the overall sense of satisfaction with the range of stimuli offered by the employer. On the one hand, this is in line with the principles established by Herzberg (1959) where the role of intangible factors is supportive rather than primary. On the other hand, modern professionals are becoming progressively less loyal to their organisations (Kassa, 2015) and their employers must utilise all available resources to avoid losing their loyalty (Chowdhury et al., 2017).

Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Results

Objective 1 was to analyse what extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli are available to contemporary organisations. This objective was addressed at the level of the Literature Review section that identified 11 factors relevant for employees on the basis of both theoretical and empirical sources (Almaaitah et al., 2017). Extrinsic factors included salary and bonuses, fringe benefits, job security, restricted working hours and career development opportunities. The intrinsic incentives group was comprised of the positive working environment, the recognition of achievements, the leadership style, managerial support, the availability of challenging tasks and employee empowerment in the form of autonomy and responsibility (Rafique et al., 2014).

Objective 2 was to explore the motivational power of these incentives in terms of increasing the loyalty of staff members towards the employer. The Literature Review section identified that both extrinsic and intrinsic factors had a positive impact on employee retention (Haider et al., 2015). However, tangible motivators were generally more powerful within the scope of both the empirical evidence and established theories (Mishra and Mishra, 2017). Specifically, Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene framework views intangible factors as additional incentives that support the ‘primary offer’ in the form of extrinsic hygiene factors. At the same time, it was discovered that the relevance of individual motivators could be different in various industries, which substantiated the need to analyse the UK service industry specifically.

Objective 3 was to evaluate the impact of these stimuli on the retention and satisfaction of employees in UK service organisations. The Analysis section established that such factors as fringe benefits, salary and bonuses, management support and job security were relevant for the intention of employees to stay with their current employer for the next 3-5 years. Hence, Null Hypothesis, which implies that there is no statistically significant link between extrinsic and intrinsic motivators and employee retention, has been rejected. In turn, Hypothesis 1, according to which extrinsic stimuli produce a strong positive impact on employee retention, has been confirmed.

Career development opportunities, salary, leadership style and positive working environment were relevant for the overall satisfaction with the range of the offered motivational incentives. This is in line with the suggestion that tangible motivators have greater relevance for staff members while intangible ones are viewed as additional and optional (Nakhate, 2016). The identified underutilisation of certain potentially powerful intrinsic instruments was found to be a concerning indicator of internal organisational limitations negatively influencing the HRM effectiveness. Thus, Hypothesis 2, which implies that intrinsic stimuli produce a strong positive effect on employee retention, has been confirmed.

Objective 4 was to formulate practical recommendations on improving staff loyalty outcomes through the use of motivational incentives. This objective is addressed in the following section.

5.2. Conclusion and Recommendations

It can be concluded that the relevance of extrinsic factors was generally more evident in the analysed UK service organisations, which is in line with the findings of Almaaitah et al. (2017). This result can be explained by the problematic political and economic situation in the country and the overall instability that stimulate employees to adhere to tangible motivators (Hestermeyer and Ortino, 2016). However, the underutilisation of intrinsic incentives identified in such dimensions as management support availability also suggests that the analysed companies may not be realising the complete potential of the human resource development instruments available to them. The analysis additionally revealed that intangible factors positively impact the overall satisfaction with HRM policies, but only a single factor has a statistically significant impact on employee retention. Therefore, the uniform approach suggested by Thiriku and Were (2016) may not be applicable to these companies. It can be suggested that intangible motivators have a lower impact on service companies’ staff members due to their greater individualism in comparison with specialists from other industries (Sutha and Chitra, 2016).

A similar number of extrinsic and intrinsic factors was relevant for ensuring the overall satisfaction of employees. This confirms the suggestions of Thiriku and Were (2016) in relation to the significance of offering a balanced set of motivators to satisfy the needs of all staff members. It is also evident that these results are similar to the empirical data from other industries provided by the studies of Al-Qeed et al. (2016), Eberendu and Kenneth-Okere (2015) and Janjhua et al. (2016). Hence, it can be suggested that contemporary organisations need to balance their offering of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators to achieve good employee retention and job satisfaction. That said, the choice of specific elements in this offering may differ depending on a particular industry. Finally, the results are in line with the theories formulated by Herzberg (1959) and Porter and Lawler (1968) as extrinsic and intrinsic rewards serve as a moderating factor determining the performance of employees and reducing the gap between their expectations and actual employment experiences.

The relevance of managerial support for the overall satisfaction and the perceived lack of this incentive reported by 48% of the respondents suggest that managers of service organisations need to pay greater attention to this stimulus. It can be recommended that new employees should receive extended job orientation and an open-door policy should be maintained to ensure that any arising problems or questions can be resolved by directly contacting superior staff members. At the same time, the lower perceived significance of intrinsic motivators for both the overall satisfaction and the current loyalty suggests two possible solutions. On the one hand, the management can focus on tangible incentives exclusively to stimulate retention in the current environmental conditions (Chowshury et al., 2017). On the other hand, these motivators are generally more expensive for organisations and may not be a viable choice for all service industry companies (Safiullah, 2014). Therefore, the use of such intangible instruments as leadership style and positive working environment can be used to complement the implemented tangible motivators in order to increase the overall satisfaction of employees.

It should be added that this study was limited in terms of its sample size, the focus on a single industry and the large share of medium and large companies in the final sample. This can make its findings non-generalisable to smaller UK companies or non-service organisations (Saunders et al., 2015). Hence, future studies may specifically focus on small, medium or large enterprises to address this problem because the size of organisations influences the motivational instruments available to them (Hestermeyer and Ortino, 2016). That said, the unstable political and economic situation in the UK can make the findings and recommendations of this dissertation inapplicable to service companies if substantial new trends emerge in the studied market.

References

Acar, A. (2014) “Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors differ for Generation X and Generation Y”, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5 (5), pp. 12-20.

Adeoye, A., Atiku, S. and Fields, Z. (2016) “Structural determinants of job satisfaction: The mutual influences of compensation management and employees’ motivation”, Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 8 (5), pp. 27-38.

Ahn, C., Heo, M. and Zhang, S. (2014) Sample size calculations for clustered and longitudinal outcomes in clinical research, London: CRC Press.

Almaaitah, M., Harada, Y., Sakdan, M. and Almaaitah, A. (2017) “Integrating Herzberg and social exchange theories to underpinned human resource practices, leadership style and employee retention in health sector”, World Journal of Business and Management, 3 (1), pp. 16-34.

Al-Qeed, M., Al-Raggad, M., Al-Shura, M., Alqaisieh, N. and Al-Azzam, Z. (2016) “The impact of ideal employee award on the retention of distinctive competencies in public sector organizations in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: A field study of public sector employees who obtained the Ideal Employee Award Civil Service Bureau”, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 7 (3), pp. 104-114.

Anderson, D., Sweeney, D., Williams, T., Camm, J. and Cochran, J. (2014) Essentials of statistics for business and economics, Boston: Cengage Learning.

Anthony, P. and Weide, J. (2015) “Motivation and career-development training programs: Use of regulatory focus to determine program effectiveness”, Higher Learning Research Communications, 5 (2), pp. 24-33.

Azeez, S. (2017) “Human resource management practices and employee retention: A review of literature”, Journal of Economics, Management and Trade, 18 (2), pp. 1-10.

Biswakarma, S. and Sharma, S. (2015) “Impact of motivation on employee’s turnover and productivity in hotels (FHRAI listed) of Kolkata”, International Journal of Innovative Research and Development, 4 (13), pp. 51-60.

Boswell, C. and Cannon, S. (2014) Introduction to nursing research, Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2015) Business research methods, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chowdhury, M., Hasan, N., Al Mamun, C. and Hasan, M. (2017) “Factors affecting employee turnover and sound retention strategies in business organization: A conceptual view”, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 15 (1), pp. 63-71.

Creamer, E. (2017) An introduction to fully integrated mixed methods research, London: SAGE.

Dainton, M. and Zelley, E. (2014) Applying communication theory for professional life: A practical introduction, London: SAGE.

Eberendu, A. and Kenneth-Okere, R. (2015) “An empirical review of motivation as a constituent to employees’ retention”, Research Inventy: International Journal of Engineering and Science, 5 (2), pp. 6-15.

Fortune, A., Reid, W. and Miller, R. (2013) Qualitative research in social work, New York: Columbia University Press.

Fowler, F. (2013) Survey research methods, London: SAGE.

Fox, D., Gouthro, M., Morakabati, Y. and Brackstone, J. (2014) Doing events research: From theory to practice, London: Routledge.

Ghosh, D. and Gurunathan, L. (2015) “Do commitment based human resource practices influence job embeddedness and intention to quit?”, IIMB Management Review, 27 (4), pp. 240-251.

Grove, S., Gray, J. and Burns, N. (2014) Understanding nursing research: Building an evidence-based practice, St. Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Gunawan, H. and Amalia, R. (2015) “Wages and employees performance: The quality of work life as moderator”, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5 (1), pp. 349-353.

Haider, M., Rasli, A., Akhtar, S., Yusoff, R., Malik, O., Aamir, A., Arif, A., Naveed, S. and Tariq, F. (2015) “The impact of human resource practices on employee retention in the telecom sector”, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5 (1), pp. 63-69.

Harder, A., Gouldthorpe, J. and Goodwin, J. (2014) “Why work for extension? An examination of job satisfaction and motivation in a statewide employee retention study”, Journal of Extension, 52 (3), pp. 1-12.

Herzberg, F. (1959) The motivation to work, New York: John Wiley.

Hestermeyer, H. and Ortino, F. (2016) “Towards a UK trade policy post-Brexit: The beginning of a complex journey”, King’s Law Journal, 27 (3), pp. 452-462.

Hofstede-Insights (2017) “UK”, [online] Available at: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/the-uk/ [Accessed on 4 November 2017].

Hui-Chin, C. and Yang, K. (2015) “Testing Herzberg’s two-factor theory in educational settings in Taiwan”, Journal of Human Resources & Adult Learning, 11 (1), pp. 54-65.

Ismail, A. and Ahmed, S. (2015) “Employee perceptions on reward/recognition and motivating factors: A comparison between Malaysia and UAE”, American Journal of Economics, 5 (2), pp. 200-207.

Janjhua, Y., Chaudhary, R. and Sharma, R. (2016) “An empirical study on antecedents of employee retention and turnover intentions of employees”, IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Business Management, 4 (5), pp. 1-10.

Johannesson, P. and Perjons, E. (2014) An introduction to design science, Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Johnson, R. and Christensen, L. (2013) Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches, London: SAGE.

Kassa, T. (2015) “Employee motivation and its effect on employee retention in Ambo mineral water factory”, Computer Science, 3 (3), pp. 10-21.

Klenke, K. (2016) Qualitative research in the study of leadership, 2nd ed., Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Kossivi, B., Xu, M. and Kalgora, B. (2016) “Study on determining factors of employee retention”, Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4 (5), pp. 261-268.

Lee, M. and Raschke, R. (2016) “Understanding employee motivation and organizational performance: Arguments for a set-theoretic approach”, Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 1 (3), pp. 162-169.

Lehmann, M. and Zetzsche, D. (2016) “Brexit and the consequences for commercial and financial relations between the EU and the UK”, European Business Law Journal, 27 (1), pp. 999-1027.

Mishra, S. and Mishra, S. (2017) “Impact of intrinsic motivational factors on employee retention among Gen Y: A qualitative perspective”, Parikalpana: KIIT Journal of Management, 13 (1), pp. 31-42.

Mitsakis, F. (2014) “The impact of economic crisis in Greece: Key facts and an overview of the banking sector”, Business and Economic Research, 4 (1), pp. 248-265.

Morrow, G., Burford, B., Carter, M. and Illing, J. (2014) “Have restricted working hours reduced junior doctors’ experience of fatigue? A focus group and telephone interview study”, BMJ Open, 4 (3), pp. 1-10.

Muchiri, C., Waiganjo, E. and Kahiri, J. (2016) “Influence of stimulating managers on organizational performance of commercial banks in Kenya”, Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 3 (3), pp. 264-278.

Muslim, N., Dean, D. and Cohen, D. (2016) “Employee job search motivation factors: An evidence from electricity provider company in Malaysia”, Procedia Economics and Finance, 35 (1), pp. 532-540.

Nakhate, V. (2016) “Critical assessment of Fredrick Herzberg’s theory of motivation with reference to changing perception of Indian pharma field force in Pune region”, The International Journal of Business & Management, 4 (1), pp. 182-190.

Natarajan, S. and Palanissamy, A. (2015) “Employee motivation & encouraging retention in the workplace: A critical study”, International Journal of Management Sciences, 5 (10), pp. 709-715.

Nemeckova, I. (2017) “The role of benefits in employee motivation and retention in the financial sector of the Czech Republic”, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 30 (1), pp. 694-704.

Nnaji-Ihedinmah, N. and Egbunike, F. (2015) “Effect of rewards on employee performance in organizations: A study of selected commercial banks in Awka metropolis”, European Journal of Business and Management, 7 (4), pp. 80-88.

Okech, V. (2015) “Human resource management practices influencing staff retention in non-governmental organizations in Kenya: A case study of Kenya Red Cross Society eastern and central Kenya regions”, Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 2 (2), pp. 1224-1242.

Osabiya, B. (2015) “The effect of employees motivation on organizational performance”, Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 7 (4), pp. 62-75.

Porter L. and Lawler, E. (1968) Managerial attitudes and performance, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rafique, A., Tayyab, M., Kamran, M. and Ahmed, N. (2014) “A study of the factors determining motivational level of employees working in public sector of Bahawalpur (Punjab, Pakistan)”, International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 4 (3), pp. 19-34.

Ribeiro, J. (2017) Business survival analysis using SAS: An introduction to lifetime probabilities, Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Rono, E. and Kiptum, G. (2017) “Factors affecting employee retention at the University of Eldoret, Kenya”, IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 19 (3), pp. 109-115.

Rovai, A., Baker, J. and Ponton, M. (2013) Social science research design and statistics: A practitioner’s guide to research methods and IBM SPSS, Chesapeake: Watertree Press.

Safiullah, A. (2014) “Impact of rewards on employee motivation of the telecommunication industry of Bangladesh: An empirical study”, IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16 (12), pp. 22-30.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2015) Research methods for business students, 7th ed., Harlow: Pearson Education.

Shmailan, A. (2016) “The relationship between job satisfaction, job performance and employee engagement: An explorative study”, Issues in Business Management and Economics, 4 (1), pp. 1-8.

Sutha, A. and Chitra, S. (2016) “Human resource management in service organisations”, Engineering and Science, 1 (3), pp. 130-134.

Thiriku, M. and Were, S. (2016) “Effect of talent management strategies on employee retention among private firms in Kenya: A case of Data Centre Ltd-Kenya”, International Academic Journal of Human Resource and Business Administration, 2 (2), pp. 145-157.

Wakabi, B. (2016) “Leadership style and staff retention in organisations”, International Journal of Science and Research, 5 (1), pp. 412-416.

Wei, L. and Yazdanifard, R. (2014) “The impact of positive reinforcement on employees’ performance in organizations”, American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 4 (1), pp. 9-12.

Wiles, R. (2012) What are qualitative research ethics?, London: Bloomsbury.

Wynarczyk, P., Watson, R., Storey, D., Short, H. and Keasey, K. (2016) Managerial labour markets in small and medium-sized enterprises, London: Routledge.