Written by Philip S.

Abstract

The current dissertation aims to evaluate the impact made by diverse motivational practices on the individual employee performance in software SMEs located in London. It is argued that the methods of boosting the motivation of the personnel can be produced from the key theories of human motivation and the concept of leadership. Primary data is gathered to achieve the outlined purpose. It is shown that the employees of the investigated firms are predominantly affected by monetary remuneration, workplace relationships, employee development and emotional support. A statistically significant link between motivation and individual performance is identified. Generalisability is considered as the main limitation of this study.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement and Rationale for the Study

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) constitute a valuable part of the economy of the European Union with as many as 99% of all firms in the EU being considered as SMEs (Gantenbein et al., 2014). Given the size of these companies, it is expected that SMEs face significant challenges related to their operations. This was exemplified by Todorov and Smallbone (2014) who asserted that SMEs experienced difficulties in meeting the demands of the end consumers as well as being hindered in terms of corporate governance. This statement shows that the issues of employee motivation and performance are crucial for SMEs to successfully compete with large corporations and other market actors. The managers of these organisations have to employ effective and sensible motivational practices in order to account for the outlined dimensions.

However, the link between these methods and employee performance remains underexplored in academic literature in the SME context. For instance, while Pittino et al. (2016) investigated the effectiveness of such practices as intensive employee training, little evidence was given by the authors regarding motivation. Onkelins et al. (2016) were of the opinion that investments in human capital expressed through wages and employee training increased organisational productivity, but did not consider the dimension of motivation directly. Finally, Love et al. (2016) asserted that SME performance was directly related to how experienced a particular company was, but failed to outline a relationship between this factor and the personnel of SMEs. The above examples show that there is a significant research gap regarding the issue of personnel effectiveness in SMEs. This is addressed by the current study.

It is proposed that the findings of the research should be of interest both to the academic world and to the managers of SMEs. In terms of theory, this project aims to define a link between the concepts that are underrepresented in modern empirical articles, as shown above. This should give other scholars a theoretical basis for subsequent research related to the chosen subjects. In addition, the research outcomes can be used to produce practical suggestions pertaining to what methods and practices should be used in SME management to keep the personnel motivated and ensure a high level of performance. At the same time, it is acknowledged that the framework of individual efficiency could include aspects not directly related to motivation such as job satisfaction, abilities and skills. This means that the explanatory power of this dissertation is limited by the chosen focus.

1.2. Research Focus and Background

The research project is focused on software SMEs located in London. The geographical emphasis of the study can be justified by stating that London is a crucial area for the digital sector in the UK (Heath, 2015). Specifically, the number of software companies has grown by 46% over the last 5 years in London alone and the overall labour force for the sector now equals 200,000 people (Heath, 2015). It was also expected by Richards (2016) that the demand for software services would grow in the future due to the vital role played by software in such areas as social services. However, Richards (2016) also stated that the UK software industry was in need of clear communication between the employers and their subordinates as well as highly skillful employees. Both of these challenges are linked to personnel motivation and performance, further rationalising the choice of the UK and London in particular.

As for software SMEs, Rahman et al. (2016) investigated the impact of technological innovation on SME survival and concluded that an organisation’s ability to produce valuable insight was crucial for SMEs. Furthermore, Lee et al. (2016) supported these findings by stating that knowledge management was essential for Malaysian SMEs. Since the human capital of SMEs is a noteworthy organisational resource producing innovation, the above arguments placed an emphasis on the employees of SMEs worldwide. Given that software is a highly knowledge-intensive setting, these points are especially true for this industry, thus justifying the choice of software firms. On the other hand, it is admitted that the relationships established in this work may not be applicable to SMEs in other sectors (e.g. manufacturing).

1.3. Research Aims and Objectives

The research project aims to investigate into the determinants of the individual performance levels among the employees of software SMEs in London. This goal is achieved by gradually addressing the following research objectives.

- To identify the major motivational practices adopted by modern organisations.

- To establish a theoretical link between employee motivation and performance.

- To measure the impact of the selected motivational practices on employee performance in the British software sector.

- To suggest new methods and ways through which the individual performance in software SMEs can be stimulated.

1.4. Structure of the Study

It is posited that a five-chapter structure is sufficient to complete the identified research goals. Chapter 2 conducts an extensive literature review to create a theoretical framework of the study and establish the main academic theories and framework related to the concepts of employee motivation and performance. Chapter 3 complements this by outlining the design of the study and the methods, through which the aim of the project is planned to be achieved. The gathered evidence is analysed in Chapter 4 to examine the main research findings. These outcomes are discussed in detail in Chapter 5, which also summarises the study and provides practical suggestions to the managers of software SMEs.

1.5. Limitations of the Study

Generalisability is an important, expected limitation of the study. This concept refers to the degree to which the research findings are extendable to other contexts, such as other geographical areas or industries (Saunders et al., 2015). Since the current work is conducted on software SMEs in London, its findings might not be applicable to other SMEs operating in different sectors. For instance, manufacturing SMEs may place bigger emphasis on the motivational practices giving a higher level of control to the management to ensure that the necessary quality standards are upheld throughout the organisation. While this is a noteworthy shortcoming, the study had to limit its focus to a specific setting to produce accurate and sensible findings, meaning that little could have been done to increase the degree of generalisability.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1. Measurements of Employee Performance

Before discussing the issue of motivation, it is appropriate to examine how employee performance can be conceptualised within modern companies. For instance, Armstrong and Taylor (2014) noted that the process of performance assessment was largely two-dimensional. Specifically, the authors’ main idea was that the employees had to display appropriate workplace behaviours as well as achieve company-established goals in order to be considered efficient (Armstrong and Taylor, 2014). The main implication of this model is that performance could be defined as the degree to which the conducts of the staff correspond to what is expected by the company as well as efficiency. This measurement technique was evaluated as positive by Edinger and Sain (2015). The scholars argued that by rewarding initiative even if it resulted in failure firms could foster innovative organisational cultures (Edinger and Sain, 2015). At the same time, this approach can be criticised due to the fact that Armstrong and Taylor (2014) provided no clear guidelines regarding what specific conducts and goals should be considered important across different organisational contexts.

Interestingly, Armstrong (2015) presented a contrasting approach to performance appraisal by claiming that managers could rank their subordinates along a series of pre-determined dimensions. According to this framework, performance is the level, to which an employee’s actions are aligned with the ideals of his or her employers (Armstrong, 2015). This is different from what was stated by Armstrong and Taylor (2014) as the subjective opinions of managers are essential, as opposed to specific goals and objectives. However, this is also a substantial shortcoming. Since the management is given full control over the performance assessment process, the results may be non-indicative of the actual individual performance of the staff.

Both of the outlined techniques were expanded upon by Shields et al. (2016) who provided an in-depth explanation of the predictors of work performance. This theory is displayed graphically in the next figure.

It is observed that performance was defined by Shields et al. (2016) as a sum of multiple components, namely skills, knowledge, self-concept, social role and values, motives, and personality traits. The key criticism of this framework is that it can be difficult to examine all of the mentioned aspects by relying on the measurement tools available to modern organisations (e.g. goal setting). To account for this, Shields et al. (2016) also included the Emotional Intelligence (EI) approach of Goleman (1995) as a metric of individual effectiveness. Goleman (1995) presumed that high performance correlated with 5 attributes, specifically, self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skill. However, it is questionable whether the ideas of Goleman (1995) are applicable to this work. The EI effectively focused on the internal characteristics of the employees while this study emphasises the role played by managerial practices and activities. Nevertheless, the above arguments highlighted that contemporary firms may struggle with influencing all of the factors affecting employee performance, which might be reflected in the results of the study.

One of the main limitations of the points given in this section is that the definitions of employee performance and its measurements might not be static. Rusu et al. (2016) demonstrated that internal organisational context was vital in terms of this dimension. For example, the culture of a particular company could influence what was expected of its personnel and what techniques were implemented to assess effectiveness (Rusu et al., 2016). This means that the models and theories examined previously may not be applied consistently in different software SMEs, thus limiting the applicability of these ideas to the study. Gaynor (2015) also was of the opinion that there was a general tendency to exaggerate individual performance in modern organisations, leading to inaccurate measurements and reward distribution. While the degree to which this theory is applicable to software SMEs in London is unknown, this may indicate that the perceptions held by the employees of these firms may be non-representative of their actual effectiveness.

2.2. Key Frameworks of Employee Motivation

The key models of employee motivation are reviewed to determine the most significant motivational practices that could be adopted by the management. For instance, Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs is based on the assumption that individuals are primarily motivated by satisfying specific pre-determined needs, which are displayed graphically below.

In terms of actual managerial activities, the theory of Maslow (1943) would translate into methods and actions that could consistently satisfy the lower-level needs and maintain a workplace environment capable of addressing the higher-level components of the ideas of Maslow (1943). This was supported by Villafiorita (2014) who claimed that placing an emphasis on the constituents of Maslow’s (1943) pyramid was highly valuable for project management. Consequently, Fabricant et al. (2014) outlined some methods that could address the dimensions of Maslow (1943) such as meeting OSHA standards (safety), health care (safety), office parties and sports leagues (social), recognition programmes (self-esteem) and internal promotions (self-actualisation). Thus, it can be concluded that the key benefit of the paradigm of Maslow (1943) is that managers can rely on a list of specific practices addressing the aspects defined above. Nonetheless, generalisability serves as the main limitation of the discussed factors. Page (2015) questioned whether the rigid hierarchy of Maslow (1943) was followed by actual employees. In other words, while the categories of Maslow (1943) could be sensible, their order in the pyramid may vary across individual contexts (Page, 2015).

The above analysis can be complemented by relying on the work of Hitka and Balazova (2015). The researchers identified the following practices that could be connected to the needs discussed by Maslow (1943), namely the opportunity to apply skills (self-actualisation), salary (esteem), job status (esteem), internal promotions (self-actualisation) and achievement recognition (esteem). However, the context of the study was limited to the hospitality industry in Slovakia and Austria, decreasing the applicability of the findings to this dissertation. Notably, Lee and Raschke (2016) asserted that fostering friendly relations between the employees can increase motivation, thus lending support to the social needs of Maslow (1943). On the other hand, this study only used secondary data, meaning that this outcome may not be indicative of the situation within modern organisations.

The mentioned criticism of Maslow (1943) was expanded upon by Fabricant et al. (2014) who were of the opinion that individuals could differ in terms of how they ranked various managerial practices. Specifically, it was stated that some employees could only be affected by extrinsic bonuses and remuneration while others preferred to focus on self-fulfillment and internal feelings (Fabricant et al., 2014). The key implication of this result is that managers are faced with a significant challenge of addressing the needs and wishes of different subordinates. Nonetheless, this perspective was not supported by Herzberg (2003) who claimed that internal motivation was more crucial than the external techniques. This is illustrated in the next figure.

According to Herzberg (2003), employee motivation could be affected by two groups of factors, namely motivation and hygiene characteristics (Samson and Daft, 2015). The first category refers to the feelings of achievement, recognition, responsibility, work enjoyment and personal growth, which are consistent with the higher-level needs of Maslow (1943). In turn, the hygiene aspects are mostly external and consist of pay, policies, the workplace environment and the relevant relationships (Samson and Daft, 2015; Daft, 2014). Herzberg (2003) presumed that implementing new practices and activities related to hygiene (e.g. increasing wages) was sufficient to decrease dissatisfaction, but not enough to actually raise the level of engagement, which could only be done by relying on motivators. The main strength of the ideas of Herzberg (2003) is that the scope of the attributes defined above encompassed a wide variety of tools and practices. At the same time, it is questionable whether the relationships established by Herzberg (2003) are applicable to different personalities.

Turning now to the empirical evidence related to the ideas of Herzberg (2003), Zamecnik (2014) ranked the influence of motivational practices. One of the key findings of the study was that its participants were primarily affected by personal responsibility and the workplace atmosphere, which is consistent with the ideas of Herzberg (2003). However, pay and interpersonal relations were also among the most significant aspects examined by Zamecnik (2014), exemplifying that the generalisability of the Herzberg’s (2003) framework is low. Nonetheless, the scope of the project of Zamecnik (2014) was limited to a single company in Eastern Europe, entailing that the ideas of Herzberg (2003) might find more support within the context of the study. In contrast to Zamecnik (2014), Lau and Roopnarain (2014) asserted that non-financial measures (e.g. verbal feedback) were vital tools of enhancing employee motivation and performance while monetary rewards failed to achieve a similar effect within the investigated setting. At the same time, the research sample was limited to middle line managers only, meaning that employees in other positions may have behaved differently.

A contrasting perspective on employee motivation was provided by Adams (1963) in the Equity Theory. According to this model, the level of employee motivation is dependent on the results of the comparison between inputs and outputs (Brinkman et al., 2014). The inputs were defined by Adams (1963) as a sum of all the efforts displayed by an individual during his or her professional activities. In turn, the outputs consisted of the benefits offered by the workplace including monetary bonuses, verbal praise, recognition, responsibility and job security. While these attributes are consistent with what was stated by Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003), Adams (1963) suggested that the results of the outlined comparison could often be subjective and dependent on the inputs and outputs received by other employees. Nevertheless, no empirical evidence was given by Adams (1963) regarding the factors moderating the results of the ‘inputs-outputs’ evaluation.

Turning now to the empirical evidence related to the ideas of Herzberg (2003), Zamecnik (2014) ranked the influence of motivational practices. One of the key findings of the study was that its participants were primarily affected by personal responsibility and the workplace atmosphere, which is consistent with the ideas of Herzberg (2003). However, pay and interpersonal relations were also among the most significant aspects examined by Zamecnik (2014), exemplifying that the generalisability of the Herzberg’s (2003) framework is low. Nonetheless, the scope of the project of Zamecnik (2014) was limited to a single company in Eastern Europe, entailing that the ideas of Herzberg (2003) might find more support within the context of the study. In contrast to Zamecnik (2014), Lau and Roopnarain (2014) asserted that non-financial measures (e.g. verbal feedback) were vital tools of enhancing employee motivation and performance while monetary rewards failed to achieve a similar effect within the investigated setting. At the same time, the research sample was limited to middle line managers only, meaning that employees in other positions may have behaved differently.

A contrasting perspective on employee motivation was provided by Adams (1963) in the Equity Theory. According to this model, the level of employee motivation is dependent on the results of the comparison between inputs and outputs (Brinkman et al., 2014). The inputs were defined by Adams (1963) as a sum of all the efforts displayed by an individual during his or her professional activities. In turn, the outputs consisted of the benefits offered by the workplace including monetary bonuses, verbal praise, recognition, responsibility and job security. While these attributes are consistent with what was stated by Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003), Adams (1963) suggested that the results of the outlined comparison could often be subjective and dependent on the inputs and outputs received by other employees. Nevertheless, no empirical evidence was given by Adams (1963) regarding the factors moderating the results of the ‘inputs-outputs’ evaluation.

The ideas of Adams (1963) were indirectly supported by Sanyal and Biswas (2014). The researchers investigated the software industry in India and concluded that in order to feel motivated the personnel of software firms had to be provided with a wide range of outputs such as internal promotions and sensible job design (Sanyal and Biswas, 2014). On the other hand, the inputs of the study participants were not investigated extensively by Sanyal and Biswas (2014). Interestingly, Adams (1963) implied that individual perceptions could influence workplace motivation. This was not rationalised by the research outcomes obtained by Chatzopoulou et al. (2015). The study was conducted during a period of recession in Greece, which seemingly should have increased the subjective importance of all financial motivational practices. However, the findings of the study disproved this assumption, instead showing that non-monetary methods such as job design were crucial.

Finally, the goal setting theory of Locke and Latham (1990) is considered briefly in the study. Locke and Latham (1990) claimed that motivation could improve if clear, challenging and relevant goals were established by the management. This model was supported by Asmus et al. (2015) who conducted an experiment involving 4 groups of individuals. The study concluded by arguing that groups that followed concise and sensible aims were 13-15% more productive than other study participants. Nonetheless, it is unknown whether the results of the experiment of Asmus et al. (2015) are applicable to software SMEs. In addition, Welsh and Ordonez (2014) asserted that high performance goals could diminish self-regulatory capacity of the employees as well as lead to unethical behaviour.

2.3. Leadership as a Motivational Strategy

According to Armstrong and Taylor (2014), the dimension of leadership has to be considered whenever the issues of employee motivation and individual performance are raised. The authors claimed that the interaction between leaders and their followers could be vital in achieving the established organisational objectives (Armstrong and Taylor, 2014). This was justified by Syafii et al. (2015) and Aziz et al. (2013) who demonstrated that the link between leadership and performance both at individual and organisational levels was significant. On the other hand, Syafii et al. (2015) preferred to not define leadership styles as motivational practices, instead considering them as a dedicated unit of analysis. While this may signify a caveat with the ideas of Armstrong and Taylor (2014), it can also be argued that the difference between the two sources is purely conceptual, thus justifying the perspective adopted in this work.

One of the key caveats associated with the above argument is that leaders can differ significantly in terms of their preferred styles of governance and the resulting motivational practices. For instance, Lan and Chong (2015) investigated the concept of transformational leadership, which was defined via the following figure.

It is shown that transformational leadership is reliant on 4 attributes, namely being a visionary, upholding morals, as well as being charismatic and considerate (Lan and Chong, 2015). In terms of observable workplace activities, these qualities could be expressed through being a role model by constantly upholding the required ethical and efficiency values, establishing high performance expectations and providing emotional support to the regular employees (Mhatre and Riggio, 2014). The basic assumption at the core of transformational leadership is that these techniques should motivate employees to display a higher level of individual effectiveness (Mhatre and Riggio, 2014). This suggestion was shown to be correct by Wang et al. (2016) who established a direct correlation between transformational leadership and team creativity (which can be thought of a as a metric of performance). On the other hand, the study also admitted that transformational leaders’ influence was limited by the existing intrinsic motivation of the personnel, thus showing that leadership alone is not sufficient to ensure high motivation and performance (Wang et al., 2016). Furthermore, Aga et al. (2016) demonstrated that transformational leadership contributed to project success by improving efficiency. However, the cultural context of the study was limited to Ethiopia, meaning that the above findings may not manifest in the UK context.

In contrast to transformational leadership, the transactional leadership style is mainly focused on identifying clear objectives and assigning tangible rewards to these goals in the hopes that the personnel would be sufficiently motivated to achieve the established aims (Diechmann and Stam, 2015). Notably, this means that transactional leadership is effectively limited to the motivational practices examined in the previous section of this chapter. However, this does not mean that this style is ineffective with respect to employee motivation and performance. It can be argued that “transformational and transactional leadership are equally important in in encouraging employees to generate ideas that move the organisation forward” (Diechmann and Stam, 2015, p. 204). On the other hand, Tyssen et al. (2014) was of the opinion that transactional leadership was only beneficial for tasks that did not introduce any new responsibilities or tools, which is a vital shortcoming of this style.

Turning now to the dimension of servant leadership, Chiniara and Bentein (2016) argued that servant leaders were primarily concerned with the development needs of their employees. It was asserted that by implementing training programmes and being attentive to their followers’ behaviours servant leaders satisfied the needs related to the aspects of autonomy, competence and relatedness, thus linking servant leadership and the theories of Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003) (Liden et al., 2008). Nonetheless, because the study of Chiniara and Bentein (2016) was limited to the context of Canada, the impact of servant leadership within the setting of the study might be different. The main outcomes of Chiniara and Bentein (2016) were also supported by Yoshida et al. (2014) who stated that servant leadership enhanced employee innovativeness and creativity in the Asian context. On the other hand, the researchers also claimed that servant leadership mainly interacted with the existing innovation climate within a team, implying that this factor has to be addressed first to benefit from the practices associated with this leadership style.

Finally, laissez-faire leadership effectively consists of the leaders distancing himself or herself from active participation in governance (Kumra et al., 2014). Instead, the followers are left free to take their own decisions, but can still request support whenever necessary (Kumra et al., 2014). This increases the degree of professional responsibility delegated to the personnel and also seemingly enhances the significance of their professional achievements in accordance with the ideas of Herzberg (2003). At the same time, it is questionable whether this suggestion is true in real-life organisational contexts. For instance, the study of Asrar-ul-Haq and Kuchinke (2016) asserted that this leadership style could lead to a decrease in motivation and individual performance. Although the work of Asrar-ul-Haq and Kuchinke (2016) was limited to the Pakistani setting, this outcome raises the issue of whether the practices associated with laissez-faire leadership are universally beneficial.

It is acknowledged that the outlined relationships may go beyond the delimitated leadership styles. For instance, Ghani et al. (2015) analysed the individual performance of the public-sector employees in Indonesia and noted that leader personality was a crucial influence in this context. While the individual characteristics of leaders could potentially have an effect on their preferred activities, no such link was outlined in the study. Luo et al. (2015) adopted a different perspective regarding the dimension of leadership by arguing that the self-concepts of the employees have to be examined when discussing leader-follower interactions. Since the researcher is unable to include all potential impacts and factors related to leadership, and has focus on a pre-determined set of theories and frameworks, the explanatory power of the study is limited.

The below table summarises leadership-centric motivational practices.

2.4. Connecting Employee Motivation and Individual Performance

This section discusses the relationship between employee motivation and individual performance. Chen et al. (2016) asserted that firms who treated their employees well produced more innovations and patents than all other companies, which was attributed to the individual effectiveness of their personnel (Ghaly et al., 2015). Nevertheless, it is questionable whether the definitions used by Chen et al. (2016) referred to the frameworks of employee motivation examined above. For instance, the authors explicitly stated that the mentioned result was not caused by job security, which was a vital component of the approaches of Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003).

Academic support to the results discussed by Chen et al. (2016) was given by Ashford (2014). Ashford (2014) discussed the AMO model, which is graphically illustrated in the next figure.

According to Ashford (2014), motivation is one of the crucial factors influencing the level of individual effectiveness. On the other hand, the AMO model also highlights that motivation has to be supported by the relevant skills and abilities as well as valuable workplace opportunities. This means that while the effect of motivation is significant, its impact on employee performance is ultimately limited. The findings of Chen et al. (2016) were also rationalised by Wang and Hou (2015) who investigated knowledge sharing behaviours in organisations. It is posited that the distribution of internal insight is highly valuable to technology-intensive industries, thus making the work of Wang and Hou (2015) applicable to this study. The researchers employed the concepts of hard (explicit benefits bestowed by the place of employment) and soft (feelings and emotions) as the main factors influencing the frequency, with which valuable information was shared by the personnel (Wang and Hou, 2015; Kankanhali et al., 2011). Both soft and hard rewards were consistent with the approaches of Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003). Interestingly, while the link between employee motivation and individual performance was confirmed by Bedarkar and Pandita (2014), the authors’ framework of the study was limited to leadership and workplace relationships, highlighting that not all practices defined in the previous section are actually adopted in modern companies.

One of the key criticisms of the arguments presented above is that individual performance is also dependent on the factors going beyond the dimension of motivation. For example, Osman et al. (2016) demonstrated that internal organisational innovation related to products, processes and technologies used also had an impact on employee effectiveness. Schepers et al. (2015) highlighted that role conflict could also achieve a similar effect. The influence of national and organisational settings can also be considered as a significant caveat. Taguchi (2015) demonstrated that part-time workers in Japan were primarily motivated by job design and monetary remuneration.

In contrast, full-time staff were affected by employee training and financial bonuses (Taguchi, 2015). This raises the issue of why some motivational practices are effective while others fail to produce a meaningful response. Another notable shortcoming was identified by Nair and Salleh (2015) who analysed fairness in the workplace. The researchers concluded that the perceived degree of justice concerning the implemented methods (e.g. performance appraisal systems) was highly important in terms of employee motivation and performance. This example shows that the relationships at the core of this study may be moderated by a wide variety of other factors.

2.5. Chapter Summary and Theoretical Framework

The main points discussed in Chapter 2 are summarised to create the framework of the study. It was demonstrated that managers could rely on a wide variety of motivational practices to influence the feelings of their subordinates. In turn, motivation had a relationship with individual performance. Given the limitations of the approaches discussed in Section 2.1, no specific measurements of efficiency are introduced in the following model.

The following hypotheses are proposed based on of the displayed framework.

H1: The use of motivational practices increases employee motivation in British software SMEs.

H2: Employee motivation has a direct positive effect on individual employee performance in British software SMEs.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1. Research Philosophy

The design of the study has to be guided by appropriate academic principles, necessitating the choice of a suitable philosophical paradigm. It is acknowledged that the current research project can be conducted in accordance with the postulates of epistemology, ontology and axiology (Collis and Hussey, 2014; Harreveld et al., 2016). While ontology concerns the nature of reality, axiology pertains to the investigation of ethical values (Wilson, 2014; Collis and Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2015). These definitions entail that both of these doctrines are inapplicable to the current dissertation. On the other hand, epistemology refers to the relationship between the inquirer and the subject of analysis by determining what knowledge should be considered acceptable. Since the attainment of the research objectives requires collecting data related to the perceptions of the employees of software firms in the UK, this is highly beneficial.

According to Saunders et al. (2015), the choice of epistemology has to be followed by deciding one of the three philosophical stances, namely positivism, interpretivism and realism. Interpretivism is primarily focused on studying human behaviour, which makes this doctrine advantageous for business research (Saunders et al., 2015). The main assumption at the core of interpretivism is that reality is inherently subjective, which should be reflected in the research process (Myers, 2013). However, while interpretivism possesses a significant degree of explanatory power, the generalisability of interpretivistic research is significantly limited (Saunders et al., 2015). This shortcoming is not applicable to positivism, which is akin to natural science research in that the researcher has to distance his or her personal values from the process of investigating the chosen subject (Fox et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the study of human behaviours which is attempted by this work can be more complex than natural sciences research, which means that positivism would not be able to explain all of the phenomena discussed in the dissertation. This is why the stances of interpretivism and positivism are combined in the study to achieve the established research objectives.

3.2. Research Approach

The choice of the research approach effectively determines the type of logical reasoning used in the work (Saunders et al., 2015; Given, 2015). Helin et al. (2014) asserted that organisational studies could either be inductive or deductive. Induction was defined as a mechanism of experimental analysis, meaning that the inductive research outcomes are produced by observing the trends and patterns in the gathered evidence (Helin et al., 2014; Deegan, 2014). Induction is highly compatible with studies related to human behaviours and perceptions since this approach allows for providing alternative explanations of the research findings that are not necessarily constrained by the existing body of knowledge on a particular subject (Saunders et al., 2015). This argument raises the applicability of induction to the current project. At the same time, induction is inseparable from the context in which a given study was conducted (Saunders et al., 2015). This entails that the reliability of inductive research is low, which is a significant shortcoming.

In contrast, deduction pertains to the relationship between a specific set of proposed hypothesis and the real-world evidence (Cohen, 2015; Lamont, 2015). This paradigm advocates the development of theories and assertions on the basis of what is already known about the chosen focus of the study (Newsome, 2015). These ideas are then measured against the data gathered during the research project to examine their validity in a particular setting. Since deduction is largely based on the publically available knowledge regarding a specific theme, this approach is associated with high validity and reliability (Saunders et al., 2015). At the same time, the use of deduction can significantly limit the number of interpretations that could be proposed for the obtained knowledge (Saunders et al., 2015). While this is a notable caveat, deduction is chosen for the study to benefit from the outlined advantages of relying on this approach.

3.3. Research Strategy and Data Collection

This study follows the quantitative research strategy. Dagnino et al. (2016) demonstrated that this tactic has traditionally been used in business studies for the last 40 years, which substantiated the choice of a purely quantitative inquiry. This was also noted in the book of Little (2014) who provided an example of applying quantitative methods to the study of consumer behaviour. According to Gilbert and Stoneman (2016), quantitative research is beneficial whenever the degrees of difference between something or someone have to be established, which is compatible with the goals of this study. In addition, this strategy can “explain phenomena by citing causal mechanisms” (Gilbert and Stoneman, 2016, p. 80), thus offering a substantial advantage with regards to the investigation of the motivational processes attempted in this dissertation. On the other hand, it is acknowledged that some social phenomena (e.g. biased opinions) can go beyond the explanatory power of quantitative analysis. This means that the study is unable to examine the subjective cognitive mechanisms of the employees of software SMEs.

A self-administered questionnaire survey is used to obtain primary data regarding the impact made by the identified motivational practices (Bryman, 2016). By using this method, the researcher is able to gather the necessary evidence without investing a significant amount of time into this process (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Furthermore, the respondents have the opportunity to complete the questionnaire form whenever they are able to do so, which can be highly convenient (Bryman, 2016; Bryman and Bell, 2015). At the same time, since the researcher is absent when the questionnaires are answered, the study participants cannot be provided with any real-time clarifications regarding the form (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Thus, some representatives of the sample can misunderstand the given questions and in turn provide irrelevant evidence regarding their motivation and performance.

The managers of software SMEs in the UK are contacted with a request to distribute the questionnaire survey form among their personnel. The final research sample is equal to 100 employees. Since no specific criteria are applied to this procedure, the resulting sample is reliant on the non-probability convenience sampling technique (Barragues et al., 2014). Non-probability sampling is beneficial in that this strategy is faster to implement that probability sampling (Barragues et al., 2014). Since this study was constrained in terms of time and resources available to the researcher, this is appropriate. However, Schumacker (2015) asserted that no statistical generalisations could be made on the basis of non-probability sampling due to the influence of affinity and self-selection biases. This is a significant shortcoming pertaining to the extendibility of the research outcomes to other organisational settings.

3.4. Data Analysis

The examination of the motivation and performance of the employees of software SMEs in the UK is conducted by relying on two data interpretation methods, namely graphical analysis and the linear regression model. Graphical inquiry is a sensible tool of achieving the established research objectives due to the fact that this tool allows for summarising the distribution of the answers given by the questionnaire respondents (Ekstrom and Sorensen, 2015). This should enable the researcher to quickly and accurately make inferences on the basis of the numerical evidence. This is complemented by using linear regression to establish cause-and-effect relationships between the research variables. According to Chicosz (2015), this is one of the most widespread tools of data analysis. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that such practices as descriptive statistics would have also been advantageous for this work.

3.5. Definition of Variables and the Regression Models

It is necessary to define the main variables to be used when applying the linear regression model. Since this approach allows for establishing relationships between independent and dependent units of analysis, the motivational practices from the theoretical framework of the study are considered as independent variables while employee motivation and employee performance are considered as dependent variables. Due to the criticisms towards the arguments given by Armstrong (2015), Armstrong and Taylor (2014) and Shields et al. (2016), self-reported performance is used as a metric of individual effectiveness. It is acknowledged that this measurement may not accurately reflect the evaluations produced by the management of the firms, the employees of which were included in the sample. Likert scales were used in the questionnaire to simplify the use of linear regression (Fleisher and Bensoussan, 2015). The following table provides the codes for the main variables and matches these concepts to the questionnaire items (Appendix A).

3.6. Research Ethics

A high standard of research ethics is maintained in the study due to the involvement of human participants (Dresser, 2016; ESRC, 2015). All names of the individuals and organisations included in the final research sample are anonymised to avoid disclosing potentially sensitive information. (Nakray et al., 2015). In addition, informed consent is obtained from the personnel of software SMEs confirming their agreement with the main principles of the research process. The respondents are allowed to terminate their participation at any time. Third-party software is used to password-protect a flash drive where the questionnaire evidence is kept.

Chapter 4: Findings and Analysis

4.1. Employee Characteristics: Demographics, Experience and Performance

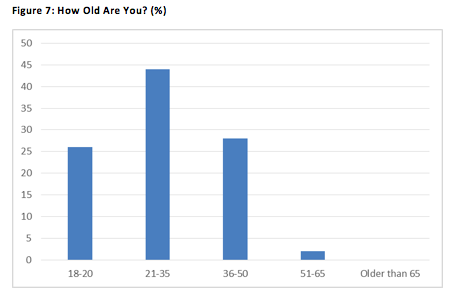

As shown in Appendix A, Questions 1-4 of the questionnaire form gathered information related to the personal characteristics of the representatives of the sample. Specifically, the age and gender of the respondents were examined to evaluate employee demographics. This is done graphically in the following figure.

The histogram displays the fact that 60% of the sample were younger than 35 years old, meaning that young adults constituted the majority of the sample. Notably, Adams (1963) proposed that subjective internal factors could influence the perception of motivational practices. The key implication of this fact for the study is that younger employees may be affected differently by what is done by their supervisors than their older colleagues. However, this can also be thought of as a limitation of this project since the research outcomes might be difficult to replicate with a sample consisting of older individuals. As for gender, Appendix B shows that the sample was highly heterogeneous in terms of this dimension with 52% of the respondents being male while the remaining 48% were female. It is assumed that this was because the composition of the workforce of software SMEs in London is diverse with respect to gender, potentially entailing that the managers of these firms have to account for this when employing various motivational practices. At the same time, since non-probability convenience sampling was employed to obtain 100 study participants, it is questionable whether the sample is truly representative of the labour force within the chosen context.

Similarly, it can be stated that the impact of motivational techniques is dependent on the professional experience of the personnel, which would be consistent with the work of Adams (1963). When asked about this factor, 24% of the sample selected the answer ‘0-2 years’ while 57% chose the option ‘2-4 years’. It can be argued that the staff who have been employed by the same companies for a longer period of time were more aware of the methods adopted by the managers of these firms, thus increasing their motivation. However, other personnel may have been motivated by the aspects not necessarily related to the established motivational activities such as a desire to impress their new colleagues and supervisors. Interestingly, despite the outlined differences, the responses provided for Question 4 (‘My workplace performance is evaluated as high by my supervisors’) were largely similar, which is exemplified below.

‘Neither’ was selected by 54% of the final research sample, making this answer the most popular among all other options. In other words, the majority of the study participants failed to provide a definitive evaluation of how their performance was seen by their managers. One possible explanation for this result is that the efficiency of the employees of software SMEs differed between tasks and contexts. Another interpretation is that the supervisors of the firms in the sample used performance measurement metrics which highlighted both positive and negative qualities of their subordinates. It is acknowledged that the performance appraisal techniques used within the investigated companies may have been incomplete or biased, which would be consistent with the criticisms given in Chapter 2 (Shields et al., 2016; Goleman, 1995). Thus, the percentages in the above figure may not be representative of the actual workplace performance.

4.2. Motivational Practices: Frequency of Use by Software SMEs

Turning now to how frequently the identified motivational practices were used by the employers of the questionnaire respondents, Question 5 pertained to monetary remuneration.

54% of the sample either agreed or strongly agreed with Question 5, which contrasted with the 16% who chose the answers ‘Strongly disagree’ and ‘Disagree’. The remaining 30% were undecided. It is observed that appropriate monetary remuneration was a priority for the managers of software SMEs in London, implying that the influence of this technique was perceived as highly important. Another possible explanation is that the average wage in the UK software industry is high, thus forcing SMEs to establish noteworthy financial rewards to avoid losing qualified personnel to their competitors. At the same time, the shortcomings of workforce outputs defined by Adams (1963) are applicable to this dimension. It is suggested that one third of the sample regularly compared their pay with what was received by other employees, which led to the fact that these individuals answered ‘Neither’. This highlights the low reliability of monetary remuneration as a motivational practice.

In contrast, the perceptions of the representatives of the sample regarding job design were more negative, which is analysed in the next figure.

It is observed that 42% of the sample strongly disagreed or disagreed with what was stated in Question 5 while another 36% were unable to provide a definite answer. This entails that the framework of job design was paid relatively little attention to by the managers of the representatives of the sample. This may be a crucial area of improvement according to Herzberg (2003), and Sanyal and Biswas (2014). However, it was stated in Chapter 2 that the ideas of Herzberg (2003) were not generalisable across individual context. This signifies that different employees might attach disparate levels of importance to the dimension of job design, potentially justifying the approach currently adopted by the managers of software SMEs in London.

Following the theoretical framework of the study, the representatives of the sample were asked about internal promotions. 48% of the sample selected the response options ‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Agree’, showing that this method was highly popular in the chosen research context (Appendix B). It is probable that the firms in the sample also wanted to save costs associated with external recruitment (e.g. spending on job advertisements), further demonstrating why internal promotions were perceived as a useful practice. On the other hand, 32% of the sample were undecided. One implication of this outcome is that external labour forces were still utilised by software SMEs in some situations. This contrast entails that while internal promotions are a valuable motivational tool, they are insufficient to address all organisational demands in labour.

As opposed to this, a total of 70% the employees included in the sample agreed or strongly agreed that their employers maintained the necessary level of safety, thus addressing the needs defined by Maslow (1943) (Appendix B). Safety was considered as crucial by the managers of the representatives of the sample, thus lending confirmation to what was stated by Maslow (1943). At the same time, this does not automatically mean that safety had an effect on employee motivation. Attention was also paid by the supervisors to workplace relationships, which is exemplified below.

A total of 52% of the sample answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’, which highlighted that explicit measures (e.g. team-building exercises) were taken by the senior staff of software SMEs to improve the quality of workplace relationships. This is in line with what was asserted by Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003). Nonetheless, 26% of the sample chose the response option ‘Neither’, potentially indicating that these efforts were not always successful in fostering friendly relationships between the personnel. The main implication of this outcome is that organisations only have a limited degree of control over the factors identified by Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003). It is admitted that a single questionnaire item is insufficient to completely validate the above suggestion.

In contrast, the opinions of the study participants regarding feedback were more divisive. This is exemplified by the fact that the percentage of respondents who strongly disagreed or disagreed with Question 10, which was estimated at 36%, was equal to the percentage of the study participants who chose the response options ‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Agree’ (Appendix B). It can be inferred that the use of feedback was inconsistent within software SMEs in London. In turn, this means that the managers employed by the firms operating in the study context did not follow a specific pre-determined approach with respect to employee motivation. This raises an issue of why some motivational practices were considered effective by the majority of the investigated SMEs while other activities were not used as frequently. This disparity is highlighted further by the dimension of goal setting.

A total of 83% representatives of the sample answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’, entailing that goal setting was one of the most widely used motivational strategies among the identified research variables. One possible explanation for this result is that the employees reacted positively to these objectives, thus justifying their use by the management. On the other hand, this finding contradicts what was noted by Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003) regarding employee motivation. While these authors stated that all needs and motivational factors had to be accounted for by modern firms, the outcomes detailed above demonstrated that such practices as regular feedback were largely ignored by the supervisors employed within the research context.

A similar contrast was observed with respect to the techniques arising from the concept of leadership.

It is shown that 43% of the sample were undecided, which demonstrated that role modelling was given relatively little attention to by the managers of the questionnaire respondents. However, the same could not be said pertaining to emotional support. As illustrated in Appendix B, a total of 53% of the study participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that their supervisors were able to consistently provide emotional aid. This exemplifies that despite being related to the same leadership style (transformational), role modelling and emotional assistance differed in terms of their perceived effectiveness within the investigated SMEs. At the same time, it is admitted that the subjective opinions and perceptions of the employees in the sample might not be representative of the actual managerial behaviours, which is a notable limitation of the outlined results.

Turning now to the use of employee development programmes, 51% of the sample selected the response options ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly agree’ when faced with Question 14. However, another 32% of the sample were unable to provide a definite answer. This result is interpreted as meaning that while the supervisors of these employees tried to implement training and development programmes, these initiatives were unsuccessful in fostering new skills and competencies. In turn, this may decrease the impact of this practice on employee motivation. As for lack of involvement, which was the final method included in the framework of the study, this aspect is analysed graphically below.

40% of the sample strongly disagreed or disagreed with what was posited in Question 15. This indicated that the motivational practice arising from laissez-faire leadership was not perceived as effective by the managers of the representatives of the sample. At the same time, 25% of the sample were undecided. This may entail that the supervisors of these employees exercised a high degree of control during some tasks, but allowed more freedom during other assignments. In turn, this discussion exemplifies that particular motivational practices could only be applied in specific situations instead of being implemented regularly. This is a valuable research finding which was not accounted for in Chapter 2 when discussing the works of Maslow (1943), Adams (1963) and Herzberg (2003).

4.3. Employee Motivation and Performance: Self-Reported Findings

The participants of the study were also asked to evaluate their motivation (Question 16) and performance (Question 17). As seen in Appendix B, 46% of the sample agreed or strongly agreed with Question 15, thus affirming that their workplace motivation was high. Nonetheless, another 33% of the respondents answered ‘Neither’, implying that their level of motivation varied. On the basis of this outcome, it can be argued that motivation is not a static factor, but rather a dynamic dimension that may be difficult to measure. On the other hand, the researcher was unable to pose any additional questions regarding this interpretation to the representatives of the sample as all data collection was dependent on the self-administered questionnaire strategy.

As for performance, a total of 46% of the sample chose the response options ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ when faced with Question 16 (Appendix B). These individuals were able to consistently deliver high performance in the workplace. One notable finding is that these results were different from what was perceived by the supervisors of the firms investigated in the study. Specifically, 54% of the sample chose the response option ‘Neither’ when asked whether their workplace performance was evaluated as high by the management. This shows a gap between what is thought by regular employees and the senior staff of software SMEs. In other words, the representatives of the study may have considered the opinions held by their managers as unfair. In turn, fairness was a crucial component of motivation as proposed by Adams (1963). The outlined result potentially means that the motivation of the questionnaire respondents was not correlated with their self-reported performance. However, statistical appraisal is needed to verify this assumption.

Moreover, the study participants were encouraged to evaluate the link between their levels of motivation and performance, and the practices employed by their supervisors. Appendix B shows that 73% of the sample agreed or strongly agreed that their workplace behaviours were dependent on what was done by the management. This entails that the employees included in the sample were highly aware of the possible impacts of various motivational practices, thus putting additional pressure on the senior staff of their organisations of employment. This outcome also was in line with the claim that the methods of improving workplace motivation could have a direct effect on what is felt and achieved by the personnel, thus lending partial support to the ideas of Chen et al. (2016), Wang and Hou (2015), and Bedarkar and Pandita (2014). That said, 20% of the sample were unable to provide a definite answer, possibly undermining the above arguments.

4.4. The Impact of Motivational Practices on Employee Performance: Statistical Analysis

As asserted in Chapter 3, the linear regression model is applied to the primary data to establish statistically significant relationships between the chosen variables. Two analyses were conducted, namely between the discussed motivational practices, and between employee motivation and employee performance. The below table overviews the main factors influencing employee motivation (EMT).

Fleisher and Bensoussan (2015) noted that the Sig. value of 0.05 could be considered as a viable criterion of statistical significance. According to this benchmark, only 4 units of analysis were found to have a notable impact on employee motivation, namely monetary renumeration (RMN), improving workplace relationships (IRH), providing emotional support (ESP), and employee training and development (EDV). The t-coefficients for these variables were positive, entailing that the above aspects had a linear positive effect on the level of motivation. This can be exemplified by arguing that higher wages and financial bonuses led to increased motivation. The same was true for IRH, ESP and EDV.

These outcomes are in line with what was stated by Maslow (1943), Herzberg (2003), Mhatre and Riggio (2014), and Chiniara and Bentein (2016). Nonetheless, only partial support is given to the ideas of these authors since the table demonstrated that not all motivational practices were equally influential. This can be explained by arguing that the employees of the firms investigated in the study valued the mentioned characteristics due to personal or external factors. Another probable interpretation is that the managers of the SMEs included in the sample frequently ignored the activities that were assigned with a Sig. value higher than 0.05. However, this suggestion is not supported by the findings appraised in the previous sections. For example, internal promotions were used frequently within the study context, but IPR was not among the statistically significant variables. Following the theoretical framework of the study, the next table examines whether employee motivation had an impact on performance.

The table revealed that employee motivation passed the benchmark of statistical significance mentioned by Fleisher and Bensoussan (2015). Moreover, the t-coefficient for the EMT variable was positive. In other words, the more motivated the representatives of the sample felt, the better their individual performance was.

This finding is compatible with the works of Ashford (2014) and Chen et al. (2016). The results of statistical analysis identified a substantial link between the desire to work felt by an employee and his or her level of individual performance. This result exemplifies that the emotional dimension is vital in modern organisational settings. In turn, the managers of SMEs and other companies are faced with a significant challenge of addressing this factor. Notably, the outcomes of the previous statistical analysis revealed that not all motivational practices were equally effective. This means that supervisors have to distinguish between the strategies that could have a valid impact on employee behaviours and the remaining techniques, which may also be a problematic process. At the same time, it is impossible to fully verify these suggestions without obtaining data related to the perceptions of the managers employed at software SMEs in London.

4.5. Chapter Summary

One of the key findings of the study was that such motivational practices as emotional support were more popular within the research context than the remaining mechanisms. A similar disparity was observed with regards to statistical analysis. Only monetary remuneration, emotional support, improving workplace relationships and employee development were presented as effective strategies. The main implication of this was that managers have to choose the most sensible activities instead of relying on pre-determined frameworks (e.g. the theory of Herzberg (2003)). In addition, it was shown that employee motivation correlated with performance, raising the importance of the emotions of the personnel.

Chapter 5: Discussion of the Findings

Since this research follows the deductive approach, its findings are compared to the works of other authors reviewed in Chapter 2. Starting from the fundamental theories of human motivation, Maslow (1943) asserted that all individuals were driven by a ranked set of needs. This assumption was partially supported by the study. The fact that monetary remuneration had a substantial effect on employee motivation could be explained by arguing that finances allow for satisfying the wishes detailed by Maslow (1943). The significance of workplace relationships, which were conceptualised by belongingness needs by Maslow (1943), was also rationalised in the study. At the same time, the low generalisability of the theory of Maslow (1943) was also confirmed in this project. Specifically, the fact that such factors as safety did not have an effect on employee motivation despite being one of the core components of the framework of Maslow (1943) showed that the strict rankings proposed by Maslow (1943) may not manifest across all individual contexts.

Furthermore, Herzberg (2003) presented a contrasting perspective by separating the relevant factors into two groups and noting that the hygiene aspects could not increase employee motivation. Limited support was given to this idea in the study. Specifically, emotional support, employee training and development, and workplace relationships all can be linked to the ideas discussed by Herzberg (2003). On the other hand, the study also highlighted that wages and financial bonuses, which were perceived by Herzberg (2003) as a hygiene attribute, had a direct and positive impact on employee motivation. This may indicate that the rigid distinction outlined by Herzberg (2003) is not applicable to modern organisations. However, it is acknowledged that the approach of Herzberg (2003) may be more suitable for firms operating in the settings beyond the research context.

The ideas of both Maslow (1943) and Herzberg (2003) were expanded upon by Adams (1963) who was of the opinion that employee motivation was dependent on highly subjective comparisons between workplace inputs and workplace outputs. The theory of Adams (1963) could serve as a potential explanation of the fact that many representatives of the sample failed to provide definite answers when asked to evaluate the motivational practices defined in Chapter 2. In other words, while the supervisors of these employees may have used such methods as job design extensively, the questionnaire respondents might have felt that this was not enough to cover the produced workplace inputs. This example shows that the framework of Adams (1963) is highly applicable to the research context. Nevertheless, because the questionnaire survey form was structured, the researcher was unable to ask any additional questions regarding the reasoning of the study participants, thus meaning that the above suggestions could not be validated completely in the current study.

Finally, the theory of Locke and Latham (1990) was disputed by the research project. The variable corresponding to this activity was not among the statistically significant units of analysis as demonstrated in Chapter 4. This was despite the fact that goal setting was used frequently within the companies included in the sample, which was observed when discussing the results of graphical analysis. One possible explanation for this is that the criticisms provided by Welsh and Ordonez (2014) are relevant for the study. Specifically, the authors argued that challenging goals could actually decrease employee motivation, which seemingly occurred for the representatives of the sample. The key implication of the outlined outcome is that simply establishing clear and meaningful objectives is not enough to boost motivation. Instead, these aims have to be assigned with valuable rewards to be effective. However, additional research is required to test this proposition in detail.

Turning now to the impact of leadership on employee motivation, Armstrong and Taylor (2014) claimed that leadership was vital in affecting the emotions and feelings of the personnel. This assertion was rationalised by the study due to the fact that such practices as emotional support and staff development were linked directly to the EMT variable. At the same time, not all practices arising from the concept of leadership (e.g. lack of involvement) were as significant as the mentioned strategies. Another criticism of what was stated by Armstrong and Taylor (2014) is that the leadership styles identified in Chapter 2 were not equally effective in boosting motivation. For instance, the importance of both transformational leadership and servant leadership was highlighted in the study. In contrast, laissez-faire leadership did not have a notable impact on the motivation of the study participants.

The above findings are consistent with the works of Lan and Chong (2015), and Mhatre and Riggio (2014) who claimed that transformational leadership was a viable technique of improving employee motivation. This was also supported in the empirical articles of Wang et al. (2016) and Aga et al. (2016). However, not all practices assigned to transformational leadership were able to affect employee motivation. Only emotional support had a noteworthy relationship with what was felt by the representatives of the sample while both role modelling and high expectations (conceptualised as goal setting) were not highlighted by the linear regression model. A probable interpretation of this outcome is that the supervisors employed by the software SMEs in London paid little attention to these practices. Another possible explanation is that the link between transformational leadership and motivation was moderated by intrinsic factors as proposed by Wang et al. (2016). It is acknowledged that further research is required to investigate the intrinsic dimension of motivation.

As for servant leadership, the main postulates of Chiniara and Bentein (2016) were found to be true within the focus of the study. Employee development through formal training programmes significantly improved personnel motivation. As the research of Chiniara and Bentein (2016) was conducted in Canada, this result raises the issue of whether training and development is a universally beneficial practice that should be implemented by companies regardless of the industrial or national contexts. However, a single questionnaire survey is insufficient to generalise this finding across a wide variety of settings. Interestingly, Yoshida et al. (2014) claimed that servant leadership was mainly dependent on the existing levels of motivation. This was not supported by the dissertation. Instead, it was shown that this leadership style had potential to significantly boost motivation by providing valuable developmental opportunities.

It was also suggested in Chapter 2 that laissez-faire leadership and the associated lack of managerial involvement could enhance motivation (Kumra et al., 2014). No such impacts were identified by the study, thus disputing the article of Kumra et al. (2014). In contrast, Asrar-ul-Haq and Kuchinke (2016) stated that laissez-faire leadership had a negative effect on motivation and performance. This criticism was not applicable to the research findings. The graphical analysis revealed that lack of involvement was one of the most inconsistently applied tools among all other research variables, potentially accounting for the above results. A valuable implication of this is that managers can vary the degree of their control between different tasks, which could mean that laissez-faire leadership is difficult to implement in real-life organisational contexts. On the other hand, the generalisability of this proposal is limited to software SMEs in London.

The final result of the study was that employee motivation had a direct positive effect on individual performance. This confirmed the outcomes of the studies of Chen et al. (2016), Wang and Hou (2015), and Bedarkar and Pandita (2014). In addition, this was in line with the AMO framework discussed by Ashford (2014). Given that motivation was at least partially dependent on the practices adopted by the management, this conclusion is aligned with the theoretical framework of the study. At the same time, Ashford (2014) was of the opinion that performance was also linked to abilities and opportunities, which could limit the impact made by motivation. Furthermore, the Sig. score for the EMT variable was equal to 0.016, which signified that the correlation between EMT and EPF was not exact. This could be attributed to the influence of such factors as role conflict, which was highlighted by Schepers et al. (2015), Osman et al. (2016), and Nair and Salleh (2015).

Chapter 6: Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Summary of the Findings

The main aim of this study was to examine the impact made by motivational practices on individual employee performance. To achieve this, it was noted that modern firms could rely on a wide variety of motivational practices related to the core theories of human motivation and leadership. These activities included, but were not limited to role modelling, monetary remuneration, the improvement of workplace relationships, goal setting and verbal feedback. This completed the first objective of the study. That said, it was noted that the academic validity of these methods and related frameworks and approaches was debatable. For instance, the theory of Herzberg (2003), which emphasised the feelings of achievement and recognition, was not supported by the empirical study of Zamecnik (2014). As for the motivational strategies pertaining to leadership, these were assigned to different leadership styles, thus showing that it was difficult for managers to apply these tools simultaneously.

A theoretical link was also outlined between employee motivation and individual performance by relying on the works of Chen et al. (2016), Ashford (2014), and Wang and Hou (2015). These researchers asserted that motivation had a direct effect on effectiveness, which in turn produced a connection between the outlined motivational practices and employee performance. The resulting theoretical framework of the study addressed the second research objective. On the other hand, it was also suggested by Schepers et al. (2015) and Osman et al. (2016) that efficiency in the workplace was influenced by other factors not necessarily arising from motivation such as role conflict. The main implication of this was that the influence of motivation was ultimately limited. In addition, it was claimed that motivation was a highly subjective dimension, which was supported by Adams (1963). This assertion exemplified the fact that not all motivational practices could be equally effective.

The main research findings supported the created theoretical model. Such methods as monetary remuneration, employee development, improving workplace relationships and providing emotional support were shown to have a direct and positive effect on employee motivation. Consequently, motivation passed the criterion of statistical significance when measured against employee performance. That said, not all of the discussed tools were employed by the managers of software SMEs in London in a consistent manner. For instance, the opinions of the representatives of the sample were highly divisive regarding lack of involvement. This exemplified a gap between theory, which was based on the assumption that the supervisors were able to follow a dedicated strategic approach to employee motivation, and practice. Another criticism of the research outcomes was that only self-reported motivation and performance were measured in the study. As shown by the graphical analysis, these perceptions can be different from what is thought by the management. The above discussion pertained to the third research objective.

As for the main theoretical and practical implications of the dissertation, it was posited that the borders between the different theories of motivation were ambiguous in real-life settings. Specifically, the resulting list of effective motivational practices included the tactics outlined by Adams (1963), Herzberg (2003) and Maslow (1943) simultaneously. This raises the issue of whether a new extensive framework of human motivation is needed to capture the full complexity of employee feelings and behaviours. In terms of practice, the study suggested that some strategies of improving motivation may be more productive than other techniques, meaning it is vital for the managers of firms worldwide to determine which exact activities are effective within their organisations of employment.

6.2. Evaluation of the Findings

Two hypotheses were proposed on the basis of the theoretical model of the study in Chapter 2. As this research is deductive, it is necessary to revisit these propositions and affirm or disprove their validity. Hypothesis 1 was partially supported by the research findings. Such motivational practices as monetary remuneration, emotional support, employee development and enhancing workplace relationships had a direct impact on the level of motivation of the questionnaire respondents. However, other methods were not among the statistically significant variables. This could be attributed to the contextual characteristics of the software industry, meaning that the remaining strategies and methods might be effective in other settings. Another possible explanation was that the managers included in the sample were inconsistent in the implementation of the tactics detailed in Chapter 2. Nevertheless, this was disproved by goal setting, which did not affect motivation despite the majority of the sample facing clear and meaningful goals in the workplace.

As for Hypothesis 2, this proposition was fully justified by the study. The application of the linear regression model revealed that employee motivation positively correlated with individual performance. On the other hand, Ashford (2014) was of the opinion that performance was also dependent on employee skills and competencies as well as the opportunities provided in the workplace. It is unknown whether the relationship between motivation and performance would be statistically significant if the outlined factors had been investigated in the study. At the same time, this criticism does not necessarily mean that motivation is not important. In contrast, the emotional well-being of the personnel and their desire to deliver high performance were shown to be crucial for modern software SMEs.

6.3. Recommendations for Software SMEs

In order to address the fourth and final research objective, it is necessary to posit managerial recommendations for the supervisors employed at software SMEs. One of the key results of the study was that some motivational practices (e.g. lack of involvement) had either been used inconsistently or delivered ambiguous results. In turn, this may have had an impact on whether these activities had the capacity to influence the levels of employee motivation. It is suggested for the senior staff of software SMEs to implement formal managerial training programmes aimed at developing strategies of raising employee motivation. This should ensure that the managers of these firms will follow viable approaches to motivation in the future. Nonetheless, it can also be argued that the creation and adoption of such developmental initiatives may require significant financial investments, which is a noteworthy problem for resource-constrained SMEs (Todorov and Smallbone, 2014).

Another possible suggestion is to create formal mechanisms of evaluating the level of employee motivation. For instance, questionnaires may be distributed among the staff to achieve this goal. Regular meetings should be conducted between the management and the regular employees to obtain qualitative evidence pertaining to employee motivation. Since it was shown above that motivation is linked to higher performance, this should give SMEs an opportunity to detect problems related to their internal practices and improve these procedures whenever it is necessary. However, it was highlighted throughout the dissertation that motivation may be difficult to measure in objective terms since this dimension can be highly personal, which was one of the main findings of Adams (1963). This entails that the data collected through the above measures may be non-indicative of the actual emotional states of the employees.