Introduction

The global pandemic forced many firms to put their strategic marketing plans on hold and accept the continuously changing status quo as an impassable barrier due to the high risks of non-performance (Fatmawati, 2021). As restrictions are being gradually lifted across the world, many practitioners are presently making their first cautious steps to testing new promotional strategies and exploring the new normal. On the one hand, online communication channels have experienced an ongoing growth stimulated by the involuntary adoption of remote orders and deliveries by thousands of customers. On the other hand, many companies are not compatible with this format due to their reliance on physical and interactive elements (Urdea and Constantin, 2020). For example, most luxury brands rely on brick-and-mortar stores with websites being viewed as supporting elements expanding customer convenience. These companies are actively looking for new ways to restore their offline communication and modify their propositions to restore pre-COVID-19 performance rates. This report explores the key trends in experiential marketing in the aftermath of the global pandemic.

Experiential Marketing

Experiential marketing is usually defined as the type of products and services promotion focused on lived memorable experiences of clients who are exposed to interactive and physical activities associated with specific brands (Batat, 2020). Successful campaigns utilising these principles engage the participants in two-way collaboration and make them immersed in company-related events instead of focusing on the direct sales of some featured items. For example, Lean Cuisine’s ‘Weight This’ promoted the personal achievements of the participants while completely ignoring the company's core offerings in the form of diet products (Padgett and Loos, 2021). Similarly, M&M flavour rooms presented visitors with fun interiors filled with unique fragrances, decor elements, foods, and beverages that were not associated with the brand itself. Another unusual pairing may be seen in the case of the Google Cupcake campaign where people were asked to use the new app from the company to take a photo and get a cupcake from company trucks in their area.

In all of these examples, the activities used in the campaign were funny, engaging, and non-intrusive (Liu et al., 2020). This may be seen as a ‘pull’ marketing strategy in general as opposed to the classic’ push’ one where clients are continuously attacked with marketing messages directly forcing them to buy specific products and services. As noted by Amoroso et al. (2021), experiential marketing is positively received by younger audiences due to their rejection of aggressive promotion tactics and their general willingness to establish relationships with brands. In some aspects, this approach is similar to meeting a new person where clients learn more about their acquaintance, get positive emotions from the communication, and are not forced to invest any resources or share some personal information (Urdea et al., 2021). This mild exposure creates a positive first impression and facilitates further collaboration via social media or physical stores. Additionally, experiential marketing usually stimulates a log of user-generated content such as colourful photos taken on company premises featuring brand names, logos, and other materials exposing the company in question to larger audiences via word-of-mouth.

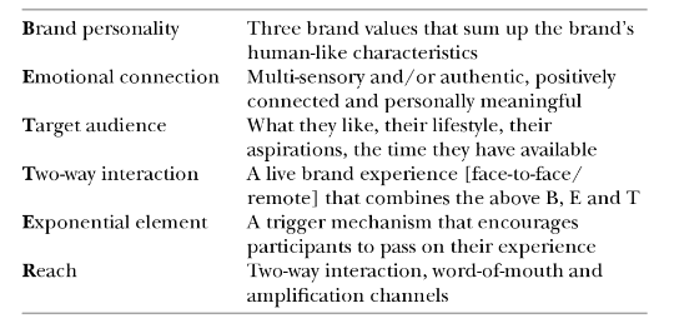

Smilansky (2017) noted that experiential marketing campaigns had to combine a number of key elements shown in the figure below, namely Brand personality, Emotional connection, Target audience, Two-way interaction, Exponential element, and Reach (BETTER) in order to be successful in achieving their goals. From a practical standpoint, these factors implied the need to create multi-sensory, interactive, and personally meaningful impressions of the company forcing the customers to get interested in it and share their positive emotions with others. As opposed to direct marketing, this stimulated organic word-of-mouth and allowed brands to gain access to the audiences they could not contact via available channels (Shahid et al., 2022). Moreover, positive company appraisals were shared by people with mutual trust, which increased the levels of genuine interest towards firms using this approach. This process was facilitated by the exponential element triggering positive word-of-mouth via such instruments as on-site photos of event visitors, the airing of videos from the event or contests among the visitors who published selfies with event-themed or company-themed hashtags on social media.

Figure 1: BETTER Model of Experiential Marketing

Source: Smilansky (2017, p.52)

With that being said, experiential marketing has a number of inherent limitations that limited its growth in the past. First, this approach is associated with substantial costs since companies have to invest resources in hosting events or setting up physical installations to create memorable connections with the brand (Juska, 2021). This strategy may not be affordable to small and medium firms with limited financial assets. Second, the overall success of experiential marketing campaigns depends on the capability to reach the targeted audiences using ‘pull’ marketing means and created the desired response patterns (Wang, 2021). In the case of failure, no positive attitudes towards the brand will be created while the firm will incur substantial sunk costs. Third, the physical nature of offline experiential marketing makes it difficult to ‘speak’ to international audiences in the case of ‘born global’ brands or achieve substantial reach in general (Berkhout, 2021). Effectively, consumers are asked to leave their ‘comfort zones’ in order to contact the firm, which may not provide sufficient motivation to do so in many cases.

Experiential Marketing During COVID-19

The global pandemic has been a major barrier for practitioners willing to use experiential marketing between 2020 and 2022 (Jiao et al., 2022). On the one hand, severe lockdowns in many areas coupled with social distancing rules made physical gatherings almost impossible to organise. Even if they were temporarily permitted in some areas, this created serious health risks as well as compliance risks that were detrimental to the positive experiences associated with brands that experiential marketers seek to create. Effectively, the seriousness of the situation at large made it difficult to get fully immersed in funny and entertaining activities for many stressed customers, which made the analysed strategy less effective (Tavares et al., 2020). On the other hand, the incurred financial losses and the increasing popularity of online sales convinced many brands to embrace digital marketing and step away from the purely physical experiential model (Widowati and Tsabita, 2017). With millions of prospective customers being locked in their homes, various forms of streaming media and VR communication technologies provided them with new ways of socialisation and entertainment.

Multiple examples of experiential marketing campaigns ran during this period have demonstrated the unique potential of multichannel experiential marketing combining both online and offline communication channels. The collaboration between the famous rapper Travis Scott and Epic Games led to the planned event in their Fortnite videogame that was viewed by 27+ million people (Howard, 2020). It included a streamed concert performance of the avatar of this celebrity followed by the sales of products related to both brands several weeks afterwards. This approach was later copied by Ariana Grande and other globally recognised artists as a new way to connect to millions of their fans around the world via unique channels. The growing potential of social metaverse concepts from Facebook and other brands as well as virtual reality headsets adoption may create a turning point in the 2020s where physical and geographic limitations could not affect the possibility of experiential marketing utilisation (Fernandez, 2021).

Another interesting example of experiential marketing is the Fuslie collaboration by Lexus (Kartajaya et al., 2021). This globally recognised brand contacted a Twitch star with 500,000+ subscribers to co-create a sedan vehicle specifically designed for gamers. The influencer launched multiple polls and ran several livestreams to engage their audience in the process. This provided the company with in-depth insights into the expectations of younger customers and offered unique exposure during the lockdown period. Additionally, the co-creation process could be characterised as user-generated content production that got thousands of people emotionally invested in the creation of the new model (Rajamannar, 2021). Lexus also launched an AR Play application offering an immersive preview of the future vehicle where they could ‘see it from the driver’s seat’ and enjoy the results of this collective effort.

New Opportunities for Experiential Marketing

While the event industry is already recovering from COVID-19, the extreme popularity of online events discussed earlier strongly implies that this new opportunity must be incorporated into the toolbox of experiential marketing specialists (Dhillon et al., 2021). Live streams and in-game visualisations will allow companies to host virtual meetings with their fans on popular gaming platforms. In the nearest future, the rise of VR and metaverses may create unique means of applying the BETTER model by Smilansky (2017) where visual and audial instruments will be supported by modern technologies and lead to new ways of entertainment and consumer engagement. These tools also offer two-way communication and utilise the means of contact already convenient for prospective clients (Jiao et al., 2022). As opposed to live events, this requires minimal adjustments or resource allocations since it only takes several clicks of a mouse to participate in such unique experiences. Virtual platforms also do not have any geographic limitations and allow brands to simultaneously run real-time marketing campaigns for millions of prospective viewers.

Similarly, the use of AR/VR tools can improve the current physical experiences by adding new sensory layers to them or making them more convenient (Berkhout, 2021). For example, the persons visiting live events can get valuable NFT items or use their smartphones in AR mode to see virtual images and item descriptions in stores. The example of the ‘Hands-Free House’ by Cheetos and Amazon shows that the integration of smart systems such as Alexa allows consumers to make complex queries and interact with brick-and-mortar facilities without talking to live consultants. While VR remains a ‘concept in development’ as of 2022, the success of the 2020 Faroe Islands ‘remote tourism’ campaign strongly suggests that it contains multiple opportunities for experiential marketers (Urdea et al., 2021). The platform developed by this brand allows users from all over the world to take control over local guides with action cameras and move them around picturesque areas to enjoy sightseeing ‘from the first-person view’.

This may be seen as a similar concept to the aforementioned Fortnite event since people can use conventional means to immerse in new experiences with minimal efforts on their part (Howard, 2020). These third-party platforms are largely similar to social media and allow individuals to interact with brands virtually and establish two-way communication. Finally, online contests represent another opportunity for user-generated content creation and brand promotion (Liu et al., 2020). This can be realised as augmented reality games where users have to physically locate virtual items in the real world to collect ‘points’ and get real items in exchange or engage in other ‘chasing games’ like the Google Cupcake campaign discussed earlier. In any scenario, these instruments stimulate people to perform various activities and get invested in these experiences in the process with brands being a source of interesting and captivating pastime options rather than active promoters of some products and services.

Conclusion

It can be summarised that the global pandemic has introduced many barriers for experiential marketing specialists but has also offered some unique technologies and communication channels that can make these practices more effective (Fatmawati, 2021). Some opportunities include online streaming events, augmented and virtual reality, and collaborations with influencers from various spheres. These practices allow marketers to realise the BETTER model by Smilansky (2017) and achieve good campaign reach and superior customer experiences. Moreover, the increasing commercial potential of Gen Z customers and their unique preferences imply that non-invasive tactics and the use of communication channels already convenient to them may be seen as the optimal strategies for promoting commercial brands to new generations (Amoroso et al., 2021). The success of Fortnite events and Twitch streams suggests that these platforms can grant access to millions of gamers and allow traditional companies to expose their products and services to audiences that cannot be accessed otherwise. Additionally, NFTs and other similar instruments can act as ‘trigger mechanisms’ for stimulating users to share their experiences with their peers from targeted customer segments and to create new forms of value from customer-brand interactions (Wang, 2021).

References

Amoroso, S., Pattuglia, S. and Khan, I. (2021) “Do Millennials share similar perceptions of brand experience? A clusterization based on brand experience and other brand-related constructs: the case of Netflix”, Journal of Marketing Analytics, 9 (1), pp. 33-43.

Batat, W. (2020) Experiential Marketing: Case Studies in Customer Experience, London: Routledge.

Berkhout, C. (2021) Retail Marketing Strategy: Delivering Shopper Delight, London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Dhillon, R., Agarwal, B. and Rajput, N. (2021) “Determining the impact of experiential marketing on consumer satisfaction: A case of India’s luxury cosmetic industry”, Innovative Marketing, 17 (4), pp. 62-74.

Fatmawati, E. (2021) “Library Experiential Marketing Strategy as a Means of Increasing Library Satisfaction in the Use of E-Resources During the Covid-19 Pandemic”, International Journal of Science and Society, 3 (4), pp. 72-84.

Fernandez, A. (2021) “Dawn of the Metaverse: How Brands Can Incorporate This Creative Initiative, [online] Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/09/29/dawn-of-the-metaverse-how-brands-can-incorporate-this-creative-initiative/?sh=3a8ca9d670e8 [Accessed on 13 July 2022].

Howard, G. (2020) “Fortnite and Travis Scott Provide Insights into How to Go to Market when the Market Disappears”, [online] Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgehoward/2020/05/02/fortnite-and-travis-scott-provide-insights-into-how-to-go-to-market-when-the-market-disappears/?sh=554c285076e7 [Accessed on 13 July 2022].

Jiao, J., Lu, F. and Chen, N. (2022) “Deriving happiness through extraordinary or ordinary brand experiences in times of COVID-19 threat”, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 1 (1), pp. 1-17.

Juska, J. (2021) Integrated Marketing Communication: Advertising and Promotion in a Digital World, London: Routledge.

Kartajaya, H., Setiawan, I. and Kotler, P. (2021) Marketing 5.0: Technology for Humanity, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Liu, H., Fu, Y. and He, H. (2020) “The Mechanism of the Effects of Experiential Marketing on Urban Consumers’ Well-Being”, Complexity, 1 (1), pp. 1-21.

Padgett, D. and Loos, A. (2021) Applied Marketing, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Rajamannar, R. (2021) Quantum Marketing: Mastering the New Marketing Mindset for Tomorrow's Consumers, New York: HarperCollins.

Shahid, S., Paul, J., Gilal, F. and Ansari, S. (2022) “The role of sensory marketing and brand experience in building emotional attachment and brand loyalty in luxury retail stores”, Psychology & Marketing, 1 (1), pp. 1-17.

Smilansky, S. (2017) Experiential Marketing: A Practical Guide to Interactive Brand Experiences, London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Tavares, F., Santos, E., Diogo, A. and Raten, V. (2020) “An analysis of the experiences based on experimental marketing: Pandemic COVID-19 quarantine”, World Journal of Entrepreneurship Management and Sustainable Development, 16 (4), pp. 327-340.

Urdea, A. and Constantin, C. (2020) “Experts’ perspective on the development of experiential marketing strategy: implementation steps, benefits, and challenges”, Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(10), pp. 502-517.

Urdea, A., Constantin, C. and Purcaru, I. (2021) “Implementing experiential marketing in the digital age for a more sustainable customer relationship”, Sustainability, 13 (4), pp. 1865-1875.

Wang, Z. (2021) “Experiential marketing: Will it affect customer citizenship behavior? An empirical study of multiple mediation model in Thailand”, Journal of Community Psychology, 49 (6), pp. 1767-1786.

Widowati, R. and Tsabita, F. (2017) “The Influence of Experiential Marketing On Customer Loyalty Through Customer Satisfaction as Intervening Variable”, Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis, 8 (2), pp. 163-180